The Cycle, Issue 8: Try A Little Tenderness

Offseason Report Cards for the Western Divisions, MLB alters the rules and the ball, Baseball’s one weird problem, a memory of Pedro Gomez, and more

In this issue of The Cycle . . .

I continue my Offseason Report Cards series by grading the Hot Stove performances of the Western Division teams.

Also:

Newswire: MLB says play ball (with new protocols . . . and a new ball?)

Inbox: On the “state of baseball” and the thing that most needs fixing

Pedro Gomez (1962–2021): A small moment from a life well-lived

Transaction Reactions: Cards keep Yadi, Mets add depth, Angels add a giant

Feedback: I want to hear from you

Closing Credits

Before we get started, word of mouth is very important to the growth and survival of The Cycle. Please spread the word, on social media and in person. Let people know how much you like The Cycle, and why they should sign up!

If you have any trouble seeing all of this issue on your email, you can read the entire issue at cyclenewsletter.substack.com. If you are already reading it there because you haven’t subscribed yet, you can fix that by clicking here:

The Cycle will be moving to paid subscriptions soon, but it remains free for now.

Offseason Report Cards: The Westing Game

Spring Training officially starts one week from today, so it’s time to evaluate how every team did this offseason. I graded the Hot Stove performances of the teams in the American and National League Central Divisions on Monday. Today, I continue with the NL and AL West.

To provide context for the grades, and maintain the theme of The Cycle, I’ve assigned each team a “season” representing where they are in the lifecycle of a contending team. Summer teams are full-blown contenders. Winter teams are deep in a rebuild. Spring and Fall are the in-between stages. Not every Spring team will blossom into Summer, and not every Fall team is headed for a cold Winter. Only Winter teams are graded on a curve. After all, an ice-cold team can only thaw so much on the Hot Stove. Also included, for context, is my rough estimation of what each team’s Biggest Needs were heading into this offseason.

Following the Season and Biggest Needs, I’ve listed all of the players each team has Added to their 40-man roster this offseason, Renewed (those are free agents they’ve re-signed), and Subtracted. The last category only includes players who appeared in the majors with the team in question in 2020 (or opted out or spent the year on the major-league disabled list) and either reached free agency or were otherwise acquired by another team after the end of the 2020 regular season. For each of those players, I’ve indicated their current team with a three-letter abbreviation in parentheses. Unsigned free agents are indicated with “(FA)”. Teams are presented in order of the final 2020 standings.

National League West

Los Angeles Dodgers

Season: Summer

Biggest Needs: third base, bench depth

Added: RHP Trevor Bauer, RHP Corey Knebel, RHP Tommy Kahnle, LHP Garrett Cleavinger

Renewed: RHP Blake Treinen

Subtracted: UT Enrique Hernández (BOS), OF Joc Pederson (CHC), RHP Pedro Báez (HOU), LHP Alex Wood (SFG), LHP Jake McGee (SFG); 3B Justin Turner (FA)

If there was one team with enough rotation depth to take the high road with regard to Trevor Bauer’s free agency and actively decide not to sign him, it was the Dodgers. So, it’s still bewildering that they’re the team that wound up landing him. As I wrote on Monday, I have my issues with that as a baseball move—it pushes deserving young talent out of the rotation—as well as a personnel decision, but I won’t deny Bauer’s potential to dominate, even if his short-season Cy Young obscures the fact that the 30-year-old righty still hasn’t fully ascended to the ranks of the game’s top pitchers.

Beyond Bauer, there’s not much here. They re-signed Treinen at a reasonable price, but their negotiations with Justin Turner are unresolved, with several teams lurking. That leaves them with Edwin Ríos as the first-string third baseman, for now, which, in turn, taps the depth of a bench that has lost Hernández and Pederson this winter. The Dodgers are betting on the kids a bit there, hoping Gavin Lux finally claims the second-base job and keeps Chris Taylor in a super-utility role, and that 26-year-old Zach McKinstry, who saw some major-league action last year, can replace Pederson as a left-handed outfield option. Elsewhere, Knebel and Kahnle are worthwhile post-Tommy John upside plays for the bullpen (Knebel for this year, Kahnle for 2022).

The bottom line is that the Dodgers need a third baseman, but (at least thus far) they got Bauer instead. That’s a decidedly mixed result from a team that is going to be facing a strong challenge from San Diego this season.

Grade: C

San Diego Padres

Season: Summer

Biggest Needs: one or two starting pitchers and some relief help

Added: RHP Yu Darvish, LHP Blake Snell, RHP Joe Musgrove, IF Ha-Seong Kim, C Víctor Caratini, CF Brian O’Grady

Renewed: UT Jurickson Profar

Subtracted: C Jason Castro (HOU), C Francisco Mejía (TBR), OF Abraham Almonte (ATL), CF Greg Allen (NYY), LHP Zach Davies (CHC), RHP Garrett Richards (BOS), LHP Joey Lucchesi (NYM), Luis Patiño (TBR), RHP Kirby Yates (TOR), RHP Luis Perdomo (MIL), RHP David Bednar (PIT); RHP Trevor Rosenthal (FA), 1B Mitch Moreland (FA), IF Greg Garcia (FA)

Padres general manager A.J. Preller, whose history with the team I outlined last week, is nothing if not aggressive. Last winter, he traded for Tommy Pham, Jake Cronenworth, Trent Grisham, Zach Davies, Jurickson Profar, and Emilio Pagán, and when those additions helped the Padres surge into contention, he added Mitch Moreland, Austin Nola, Jason Castro, Trevor Rosenthal, and Mike Clevinger at the deadline. Moreland, Castro, and Rosenthal all became free agents in November, and Clevinger had Tommy John surgery that same month, so Preller went back to work this offseason.

Preller’s primary focus this winter has been restocking his rotation with top-line pitchers from around the league, including last year’s NL Cy Young award runner up, Darvish (who arrived with personal catcher Víctor Caratini), and the 2018 AL winner, Blake Snell, who is coming off a rousing postseason in which he helped pitch the Rays deep into the World Series.

Preller also landed 25-year-old Korean shortstop Ha-Seong Kim, whom Baseball Prospectus called the best athlete in the Korea Baseball Organization last year and the best hitter to ever to come to MLB from the KBO (no small compliment given that Jung Ho Kang posted a 126 OPS+ in his first two major-league seasons). Kim hit .294/.373/.493 with 30/30 potential in seven seasons in the Korea Baseball Organization from the ages of 18 to 24. In San Diego, he will play second, pushing NL Rookie of the Year runner-up Cronenworth into a super-utility role alongside the re-signed Jurickson Profar.

So, the lineup is overflowing, and Preller has added Darvish, Snell, and Joe Musgrove to Dinelson Lamet (fourth in last year’s Cy Young voting) and Chris Paddack in the rotation, with top-100 prospects Adrian Morejon and Ryan Weathers knocking at the door (and possibly headed for the bullpen), and top-10 prospect MacKenzie Gore not far behind them.

Preller had to give some to get some. Luis Patiño, the key piece in the Snell trade, is a highly regarded rotation prospect who had already reached the majors, and he arrived in Tampa Bay with catcher Francisco Mejía, who may yet fulfill expectations as a hitter. Davies, who went to the Cubs in the Darvish deal, and Joey Lucchesi, now a Met via the three-team Musgrove trade, are viable big-league starters. Still, it’s difficult to argue with the roster Preller has assembled or the effort he has put forward in doing so.

Grade: A

San Francisco Giants

Season: late Fall

Biggest Needs: pitching, lots of it

Added: 2B Tommy La Stella, C Curt Casali, CF LaMonte Wade Jr., RHP Anthony DeSclafani, LHP Alex Wood, LHP Jake McGee, RHP Matt Wisler, RHP John Brebbia, RHP Dedniel Núñez

Renewed: RHP Kevin Gausman

Subtracted: LHP Drew Smyly (ATL),RHP Shaun Anderson (MIN), RHP Sam Conrood (PHI), LHP Andrew Suarez, IF Daniel Robertson (MIL), C Tyler Heineman (STL); RHP Jeff Samardzija (FA), RHP Trevor Cahill (FA), LHP Tyler Anderson (FA), LHP Tony Watson (FA), OF Joey Rickard (FA)

The Giants were in the bottom third of the league in run prevention last year. In November, five of their starting pitchers (Kevin Gausman, Tyler Anderson, Drew Smyly, Trevor Cahill, and Jeff Samardzija) became free agents, leaving only Johnny Cueto and Logan Webb in the major-league rotation. That was an opportunity to build back better, to borrow a phrase.

The team gave Gausman a qualifying offer, and he accepted. That’s a one-year, $18.9 million contract for a 30-year-old coming off a career-best performance, not a bad deal for the pitcher who was easily the Giants’ best last year. To flesh out the rotation behind Gausman, Cueto, and Webb, San Francisco signed righty Anthony DeSclafani and lefty Alex Wood to one-year deals worth a combined $9 million plus incentives. DeSclafani and Wood, who were rotation mates with the Reds in 2018, are only occasionally healthy or good. Wood has thrown just 48 1/3 innings over the last two years combined and hasn’t qualified for the ERA title since 2015. DeSclafani was awful in 2020 (7.22 ERA, 1.56 strikeout-to-walk ratio) and has had just one qualified season since Wood’s last.

The Giants look better on the other side of the ball, where Tommy La Stella will push Donovan Solano into a super-utility role (notice a trend here?) and Buster Posey will return for his age-34 season hoping to arrest a drop in production that started in 2018.

Grade: C-

Colorado Rockies

Season: Winter

Biggest Needs: Long-term certainty with Nolan Arenado and Trevor Story, upgrades almost everywhere else

Added: LHP Austin Gomber, RHP Robert Stephenson, LHP Yoan Aybar, RHP Jordan Sheffield, 3B Elehuris Montero

Subtracted: 3B Nolan Arenado (STL), IF Daniel Murphy (retired), CF David Dahl (TEX), C Drew Butera (TEX), RHP Jeff Hoffman (CIN), RHP Austin Goudeau (PIT), RHP James Pazos (LAD); CF Kevin Pillar (FA), OF Matt Kemp (FA), C Tony Wolters (FA), RHP AJ Ramos (FA)

I understand why the Rockies traded Nolan Arenado. He had an opt-out this fall that he seemed increasingly likely to use given the fact that the team around him has been getting increasingly hopeless. Also, the team around him was increasingly hopeless, and with Arenado entering his age-30 season, it seemed like a longshot that the Rockies would be good again before he entered his decline. So, general manager Jeff Bridich decided to cash in Arenado—who, if he didn’t opt out, was owed $164 million over the subsequent five years—and to try to use the savings to extend Trevor Story and build around the younger of their two stars.

The problem is, when they traded Arenado to St. Louis, the Rockies agreed to pay his entire $35 million salary for the coming season. If he was going to opt out anyway, that means they haven’t saved any money at all. They haven’t spent the imagined savings (actually $148 million after Colorado promised another $16 million to the Cardinals) on Story as of yet. That could change, but who wants to sign with a team that just traded Nolan Arenado? As for the quintet of players they received in the deal, including Gomber and Montero, I’d say there’s an even chance that Arenado compiles more wins above replacement for St. Louis this year than those five do in their combined major-league careers. (Read my full breakdown of the Arenado trade in Issue 5.)

On a far smaller scale, non-tendering David Dahl ahead of his age-27 season to save a few million bucks (he signed with the Rangers for $2.7 million) seems self-defeating, particularly when the primary benefit is clearing the way for Ian Desmond to return to centerfield. As for the swap of failed pitching prospects, Jeff Hoffman for Roberts Stephenson, that is likely to be more interesting in theory than in reality. There is literally nothing to like about what the Rockies have done this offseason.

Grade: F

Arizona Diamondbacks

Season: Winter

Biggest Needs: Smelling salts, apparently

Added: RHP Joakim Soria, RHP Humberto Castellanos

Subtracted: 1B Kevin Cron (NPB); CF Jon Jay (FA), RHP Mike Leake (FA), Junior Guerra (FA), Héctor Rondón (FA), RHP Artie Lewicki (FA), RHP Joel Payamps (FA), Matt Grace (FA)

The Diamondbacks went from 85 wins in 2019 to a 68-win pace in 2020 and have responded this offseason by . . .

Man, those crickets are loud.

Castellanos was a waiver claim. Soria is a 37-year-old the D’backs signed for $3.5 million. There is zero effort here. Weirder still, none of Arizona’s out-going free agents have signed with another major-league organization. Do the Diamondbacks actually exist, or were they just a collective hallucination?

Grade: F

American League West

Oakland Athletics

Season: Summer

Biggest Needs: shortstop, pitching depth

Added: SS Elvis Andrus, OF Ka’ai Tom, C Aramis Garcia, LHP Nik Turley, LHP Cole Irvin, RHP Dany Jiménez

Renewed: RHP Mike Fiers

Subtracted: SS Marcus Semien (TOR), 2B Tommy La Stella (SFG), OF Robbie Grossman (DET), DH Khris Davis (TEX), C Jonah Heim (TEX), LHP Mike Minor (KCR), RHP Liam Hendriks (CWS), 3B Jake Lamb (FA), RHP Yusmeiro Petit (FA), LHP T.J. McFarland (FA), Daniel Mengden (FA)

I realize that David Forst and/or Billy Beane likely had to do a fair amount of negotiating to complete the Elvis Andrus trade, which involved five players and $13.5 million accompanying Andrus and catcher Aramis Garcia to Oakland. Still, the above looks an awful lot like the bare minimum, doesn’t it? Tom and Jiménez were waiver claims. Turley and Irvin were cash payments for players that had been designated for assignment. That just leaves the Andrus trade, which was Plan D after Semien, Andrelton Simmons, and Didi Gregorius signed elsewhere (which isn’t to say the A’s seriously pursued any of those free agent alternatives). After playing at a 97-win pace for three consecutive years, the team deserved better than this paltry effort.

Grade: D

Houston Astros

Season: Fall

Biggest Needs: outfielders

Added: C Jason Castro, RHP Pedro Báez, RHP Ryne Stanek

Renewed: LF Michael Brantley, 1B Yulieski Gurriel

Subtracted: CF George Springer, IF Jack Mayfield (ATL), C Dustin Garneau (DET), RHP Humberto Castellanos (AZD), RHP Brandon Bailey (CIN), LHP Cionel Pérez (CIN), RHP Joe Biagini (CHC), RHP Chase De Jong (PIT), RHP Carlos Sanabria (KCR); RF Josh Reddick (FA), RHP Roberto Osuna (FA), RHP Chris Devenski (FA), RHP Brad Peacock (FA)

The Astros’ entire outfield hit free agency in the fall. Fortunately, the team has Kyle Tucker on the come-up and Yordan Alvarez on the comeback from surgery on both knees. They let George Springer go get his nine figures and re-signed Brantley, so they have DH and the corners covered, but their starter in centerfield right now is . . . Myles Straw? Straw has the legs and glove for the position, but his bat doesn’t belong in a competitive major-league lineup. Jackie Bradley Jr., Brett Gardner, Kevin Pillar, and old friend Jake Marisnick are still unsigned, to name a few, but any of those free agents, or any platoon assembled from them, is still a big step down from Springer.

Beyond that, I’m surprised not to see any effort to reinforce a rotation that was heavily reliant on rookies last year and lost Justin Verlander to Tommy John surgery at the end of September. Also, at 33, Báez is the second youngest of the team’s five free-agent signings. The Astros are starting to look like the Giants of the late 2010s. There are still a lot of familiar faces, but the bloom is off the rose, and the pedals are starting to fall.

Grade: C-

Seattle Mariners

Season: Winter

Biggest Needs: pitching, especially in the bullpen

Added: RHP Chris Flexen, RHP Robert Dugger, RHP Rafael Montero, RHP Keynan Middleton, RHP Domingo Tapia, RHP Will Vest

Renewed: RHP Kendall Graveman

Subtracted: 2B Dee Strange-Gordon (CIN), UT Tim Lopes (MIL),CF Mallex Smith (NYM), OF Phil Ervin (CHC), C Joseph Odom (TBR), C Joe Hudson (PIT), RHP Yoshihisa Hirano (NPB), LHP Taylor Guilbeau (AZD), LHP Nestor Cortes Jr. (NYY), RHP Zac Grotz (BOS), RHP Bryan Shaw (CLE), RHP Seth Frankoff (AZD); RHP Walter Lockett (FA), RHP Carl Edwards Jr. (FA)

You know the market is slow when were less than a week away from Pitchers and Catchers and Mariners general manager Jerry Dipoto, “the Seattle Swapper,” hasn’t added a single hitter to his 40-man roster. The Mariners needed pitching, and Dipoto . . . well, he got five warm bodies and kept a sixth, but none of them are likely to markedly improve the team. This is yet another case of a whole lot of nothing, but this time from the least likely candidate for such an offseason.

Grade: D+

Los Angeles Angels

Season: Fall

Biggest Needs: pitching

Added: SS José Iglesias, UT Robel García, OF Dexter Fowler, C Kurt Suzuki, LHP José Quintana, RHP Alex Cobb, RHP Raisel Iglesias, LHP Alex Claudio, RHP Aaron Slegers, RHP José Alberto Rivera, GM Perry Minasian

Subtracted: SS Andrelton Simmons (MIN), 2B Jahmai Jones (BAL), C José Briceño (COL), OF Michael Hermosillo (CHC); RHP Julio Teheran (FA), RHP Noé Ramirez (CIN), LHP Hoby Milber (MIL), RHP Matt Andriese (BOS), RHP Jacob Barnes (NYM), RHP Hansel Robles (MIN), RHP Keynan Middleton (SEA); RHP Cam Bedrosian (FA), IF Elliot Soto (FA)

Now here’s a team that at least did something. The Angels fired general manager Billy Eppler in September after the team failed to make even the expanded postseason. Perry Minasian, a longtime Blue Jays employee who had risen to assistant general manager with the Braves, was hired in mid-November, and he got right to work in December, trading for the two Iglesiases. José came from the Orioles for a pair of minor league pitchers to replace the team’s top outgoing free agent, Simmons. Raisel came from the Reds for Noé Ramirez and “future considerations” to upgrade the bullpen with a frontline closer. Claudio came cheap later that month, $1.125 million to become the top lefty in the Halos’ bullpen. In January, Minasian spent a similar amount ($1.5 million) to get 37-year-old Kurt Suzuki to back up Max Stassi behind the plate, then gambled $8 million on a comeback from José Quintana, who missed most of last season after accidentally slicing a nerve in the thumb on his pitching hand in a kitchen accident. February brought a low-stakes trade for O’s righty Alex Cobb and player-to-be-named-later swaps for Dexter Fowler and Aaron Slegers (the last included in Transaction Reactions below).

None of those moves are terribly exciting on their own, but, taken together, they shore up every aspect of the roster: Quintana and Cobb in the rotation, Raisel Iglesias, Claudio, and Slegers in the bullpen, José Iglesias in the infield, Folwer in the outfield, and Suzuki behind the plate. Would it have been nicer if the Angels actually spent some money and made a bigger splash somewhere? Sure, but in the context of this offseason, Minasian was busy and productive and sent a clear signal to his team and its fans that the Angels are trying.

Grade: B+

Texas Rangers

Season: Winter

Biggest Needs: pitching

Added: 1B Nate Lowe, CF David Dahl, DH Khris Davis, C Jonah Heim, RHP Dane Dunning, RHP Kohei Arihara, RHP Mike Foltynewicz, RHP Joe Gatto, RHP Brett de Geus

Subtracted: SS Elvis Andrus (OAK), OF Scott Heineman (CIN), OF Rob Refsnyder (MIN), RHP Lance Lynn (CWS), RHP Corey Kluber (NYY), RHP Rafael Montero (SEA), RHP Ian Gibaut (MIN), RHP Luke Farrell (MIN); OF Shin-Soo Choo (FA), 3B Todd Frazier (FA), 1B/OF Danny Santana (FA), UT Derek Dietrich (FA), UT Andrew Romine (FA), IF Yadiel Rivera (FA), C Jeff Mathis (FA), RHP Jesse Chavez (FA), RHP Edinson Vólquez (FA), RHP Juan Nicasio (FA)

Here’s another team that was at least trying to make something happen. It may seem strange to praise a team that was in desperate need of pitching and traded Lance Lynn, but Lynn is heading into his walk year and age-34 season, while Dane Dunning, the key player in the return, is a 26-year-old former first-rounder with all six team-controlled years remaining who appeared to established himself as a solid mid-rotation arm last year. Twenty-eight-year-old Japanese righty Kohei Arihara, signed to an inexpensive two-year deal, looks like another mid-rotation starter, and the presence of Dunning and Arihara allows the team to make an upside play on Mike Foltynewicz on an all-or-nothing $2 million deal that comes with an extra year of team control at arbitration prices if things go well.

The upside plays continue on the other side of the ball with David Dahl and Khris Davis. Dahl, who was non-tendered by the Rockies in December, is a 27-year-old under team control through 2023 who can hit when healthy but struggles to stay healthy, in part because he had his spleen removed in 2015 and is immunocompromised as a result. Davis, recently one of the game’s top sluggers, was acquired for Elvis Andrus, who had already been relegated to the bench in favor of Isiah Kiner-Falefa’s promotion to everyday shortstop for the coming year. To them, add new first baseman Nate Lowe, who struggled for playing time on the Rays’ deep, pennant-winning roster, but is just 25, under team control through 2026, and was a career .300/.400/.483 hitter in the minors.

Grade: B

Newswire

Play ball protocols

It’s official, Spring Training will begin on time, as will the 2021 regular season. Major League Baseball released a statement on Tuesday, ostensibly to detail their increased COVID-19 safety protocols for Spring Training and the regular and postseasons, but the big news contained within were the various parameters for the actual playing of the 2021 season on which the Major League Baseball Players’ Association and MLB have come to terms.

Here’s the skinny, with some additional details filled in by a report from Ken Rosenthal of The Athletic:

Spring Training will begin one week from today, on February 17, though reporting dates may vary from team to team.

The 2021 regular season will follow a regular, non-regional schedule.

The rules restricting double-header games to seven regulation innings and placing a runner on second base to start any inning after the ninth will, unfortunately, remain in place under the pretense of limiting the time spent at the ballpark.

There will be no restrictions on position players pitching.

Rosters will be 26 players, expanding to 28 in September. Each team will be allowed to bring five “taxi squad” players, one of whom must be a catcher, on road trips. Roster substitutions made due to a positive COVID-19 test can be made freely, without having to use options, outrights, or waivers to remove the substitutes from the 40-man roster. Alternate training sites will remain in use for taxi-squad players during homestands.

“Use of communal video terminals is prohibited,” per Rosenthal. Players will have access to iPads with pre-loaded content and approved in-game video that does not show the catcher’s signs.

The league’s statement makes no mention of the designated hitter or playoff format, but Joel Sherman reported on Monday that, in both cases, the rules will revert to 2019, with pitchers hitting in the National League, and ten teams qualifying for the playoffs, though further negotiations on those issues are still possible.

As for the COVID-19 policies, oversite will be managed by a joint committee comprised of one union representative, one league representative, and two physicians. PCR testing will be conducted at least every other day and symptom checks will be conducted multiple times per day. Players who test positive will be required to isolate for 10 days. Players must also wear contact-tracing devices at all times while at team facilities or during team activities. Players who were in close contact with an individual who tested positive will have to quarantine for seven days and pass a PCR test after the fifth day to return to the team. Masks, worn properly, are required for all personnel other than players on the field during warmups or the game, a rule enforced by “automatic” fines after two written warnings. Also, lineups will be entered into an app before the game, rather than exchanged in person, and any player or coach who gets within six feet of an umpire or an opposing player or coach for the purpose of an argument will be “subject to” ejection, fine, and suspension.

A new, league-wide code of conduct will govern activities away from the ballpark, including banning players from attendance at indoor gatherings of more than 10 people. Players must also avoid indoor restaurants, bars, “lounges,” gyms and spas, theaters, clubs, casinos, arcades, etc., while also obeying any additional local government restrictions. Players are not allowed to share a physical space with personal trainers who are not team employees.

Prior to reporting to Spring Training, players must quarantine at home for five days and pass a PCR and other intake tests before being allowed into team facilities. Players and other members of their households must quarantine at home for the duration of Spring Training, leaving only for outdoor and essential activities. MLB will provide PCR and antibody testing to those in the covered individuals’ households.

During regular season road trips, players are only allowed to leave the hotel for a short list of approved activities (team activities, medical reasons, a limited range of outdoor activities) and must notify a team-appointed “Club Compliance Officer” before leaving the hotel. On the road, players can only meet with family members outdoors, cannot meet non-family members who are not members of the team’s traveling party, and must get the compliance officer’s approval to congregate in the hotel with members of the traveling party. Teams are instructed to make hotel reservations on lower floors with no non-team guests allowed on those floors, and team employees are encouraged to use the stairs, not elevators. Teams will also require isolated dining areas at their hotels.

Fines and suspensions will be used to enforce the rules, with both players and teams subject to the fines. Also, I quote this because the language is so vague, “mental health and well-being resources will be provided to players and Club staff by Clubs and the parties throughout Spring Training” and the regular season. Vaccination remains voluntary but is “strongly encouraged” by the union.

Per Rosenthal, Spring Training will be limited to 75 players and 75 staff members for each team and divided into three phases as follows:

Phase 1 (arrival to Feb 20): small-group workouts of eight or fewer players spread out spatially and temporally

Phase 2 (Feb. 21–Feb. 26): some larger group workouts and intra-squad games allowed

Phase 3 (Feb. 27–March 31): Exhibition schedule. Games prior to March 14 may be shortened to five or seven innings by mutual agreement of the two managers, and managers of the team in the field can opt to end an inning prior to three outs if their pitcher has reached 20 pitches. Games from March 14 on may be shortened to seven innings by mutual agreement. Pitchers will be allowed to re-enter exhibition games

And about that ball . . .

As if all of that weren’t enough, Rosenthal and The Athletic’s Eno Sarris reported on Monday that Rawlings, with Major League Baseball’s approval and disclosure to teams, will be making small changes to the baseball this year with the intent of increasing the consistency of the ball. Those changes will have the not-entirely-unintended consequence of reducing the ball’s weight and bounciness, which could, in turn, reduce home-run rates. Per Rosenthal and Sarris, Rawlings discovered that these effects would result from winding the first layer of wool less tightly, and that doing so placed those balls closer to the midpoint of MLB’s allowable range for those specifications.

As MLB has learned all too well in recent years, small changes can have unexpected effects on the way the ball travels. Per The Athletic, astrophysicist Dr. Meredith Wills suggests that the loss of weight could counteract the reduction in bounciness (technically known as the coefficient of restitution or COR), though MLB told teams that an independent study found that, on hits of 375 feet or more, the new ball travels a foot or two less than the old one. That change, per one of Sarris and Rosenthal’s sources, could reduce home runs by about five percent.

In addition, Sarris and Rosenthal report that five more teams will use humidors this year, joining the Rockies, Diamondbacks, Mariners, Mets, and Red Sox. That means that a third of the league will be storing their game balls in humid environments that will have a similarly deadening effect on the flight of the ball.

Countering that report, however, is Wills’ own research on the balls used last season, published in this story by SI.com’s Stephanie Apstein. Wills found that roughly a third of the balls used last year had characteristics similar to the changes intended for 2021 and that those balls actually flew farther. MLB did have the new balls last year, but claims to have only used them for testing, not in games.

What could these changes look like in practice? Major League Baseball’s home-run rate reached record highs three times in the last four years. Prior to 2016, the record was 2.99 percent of plate appearances resulting in a home run, set, as you might expect, at the height of the “juiced era” in 2000. In 2016, that rate jumped from 2.67 percent the previous year to a record 3.04 percent. In 2017, it was 3.29 percent, and, after a return to 2015 levels in 2018, it jumped again in 2019 to 3.63 percent. The now-widely accepted reason for those changes, based in part on Wills’s research, was alterations, intentional or otherwise, to the ball.

In 2020, 3.46 percent of plate appearances ended in a home run. Pro-rated to a full season, that would have been 6,221 home runs, the second-most ever, just ahead of 2017’s 6,105, but well shy of 2019’s 6,776. Of course, we have to factor in efforts to reduce the length of games, such as seven-inning double-header games and the extra-inning rule. Pro-rate last year’s total number of plate appearances to a 162-game schedule and you get 179,566 plate appearances, the fewest in baseball since before the last expansion in 1998. If, rather than pro-rating last year’s 60-game season to 162 games, we apply that rate of 3.46 home runs to a rough average of 185,000 plate appearances, we get 6,401 home runs, still well shy of 2019 but also well ahead of third-place 2017.

Reducing those 6,401 home runs by five percent gives us 6,081 homers, just 24 fewer than in 2017, which was, itself, a record-breaking home-run year. So, even if the ball is deadened to the degree that MLB expects, it won’t bring us back to pre-2016 home-run levels. However, if the new ball turns out to be accidentally (“accidentally”?) juiced, as Wills’s research suggests, we’re in for yet another record-setting home-run barrage, the fourth in a five-year span.

That brings me to a reader question and my first edition of . . .

The Inbox

Eric from Maplewood, New Jersey writes:

I wanted to get your thoughts and opinions on the "state of baseball" today. As someone who has followed baseball for over 40 years, I am deeply concerned with the game I grew up with and love. The constant pitching changes, the emphasis on home runs and strikeouts, and the pace of play have made many of the games hard to watch. It is not enjoyable. I find myself getting more and more annoyed while watching. I don't find most of the games entertaining at all. I think during the pandemic, watching the older classic games definitely showed how much the game has changed (for the worst). I wonder if this is a concern for you? Do you think anything will be (or can be) done? I think if someone my age is thinking about this, I wonder what the younger generation is thinking?

I’ll try to keep my answer focused here. First, a couple of things I’m not worried about. I’m not worried about run-scoring levels. Even with the explosion of home runs, run scoring has remained in what I consider a normal range. Last year, teams averaged 4.65 runs per game. It was the same in 2017, and it dipped to 4.45 runs per game in 2018. To me, the “just right” range is between 4.1 and 4.6. If you allow for 0.05 runs of wiggle room on there, 2019 was the only season that has fallen outside of that range since 2008.

I am also not worried about the time of game. That is, I don’t want it to continue to increase, but I don’t think baseball should bother making too much of an effort to decrease it. Yes, the game has slowed down between pitches, but I’d rather let the players play than, as the old proverb says, use an axe to remove a fly from a friend’s forehead. The difference between an average time of game of three hours and five minutes and one of two hours and fifty-five minutes isn’t going to make a meaningful difference to anyone other than, perhaps, the national broadcasters who would have to cut into that next hour of programing less often. Even that is an extreme example. The chances of reducing the average time of game by an full ten minutes via a few rule changes are extremely slim.

Of course, pace of game is a different matter. What concerns me most about the game—that is, the action on the field—is the lack of action on the field. That doesn’t mean the time between pitches. Heck, in the most dramatic moments of a game, those tense showdowns with the tying runs on-base, etc., that time between pitches is a feature, not a bug. Part of what I like about baseball is the time between pitches, which allows you to think along with the pitcher and catcher, the batter, the baserunners, and the managers.

No, what concerns me most is the time between balls in play. Here’s a graph showing the percentage of plate appearances that ended in a fair ball (or foul out) since 1901:

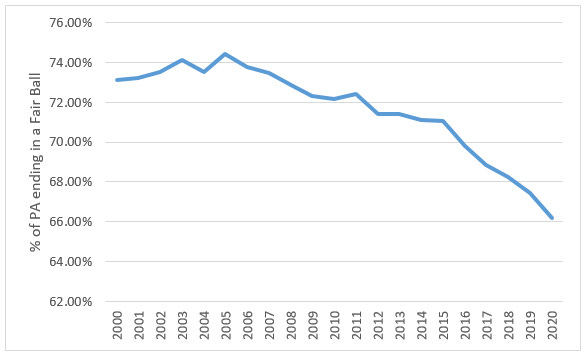

That’s a pretty steady trend away from fair balls over the last 120 years, but if you look at the very end, it’s accelerating. Here’s a close-up of the rate of fair balls since 2000:

It is plummeting. In 2020, more than a third of plate appearances ended without a fair ball for the first time in major-league history, and that was the ninth consecutive season in which the rate of fair balls reached an all-time low.

Again, these are all fair balls. I’m including home runs. Home runs are fun. Something happens. The score changes. I’d argue that triples and double plays, diving catches, stolen bases, RBI hits, and all of the more athletic plays that occur inside the fences are more fun, and that home-run rates are way too high right now, but that’s a secondary issue. Balls in play, in general, is the main one.

So why is the rate of fair balls falling so precipitously? It’s not the walks. Walk rates are up the last four years, but are still well within the established range. The walk rate in 2020 was the highest we’ve seen since 2000, but the walk rate was even higher in 1970. Nothing is out of whack there. Hit batsmen are also up, but they still don’t happen often enough to drag down that line above, which is true many times over for catcher’s interference.

No, the culprit is the strikeout.

The last year that Major League Baseball didn’t set a new all-time record for strikeout rate was 2007. Strikeouts have hit an all-time high in each of the 13 years since. Here’s that in a graph from 1901 to 2020:

Look at the slope of that line to the left of 2006. That is, by leaps and bounds, the number-one thing wrong with the game today. Is the home-run rate too high? Yes. Do I wish starting pitchers went deeper into games and were more relevant to their outcomes? Yes. Are mid-inning pitching changes a drag? Usually (some well-timed ones add drama to big situations). Would I appreciate it if there was less time between pitches and between batters? Yes. Would I accept all of those things as they are if doing so somehow enabled Baseball to fix its strikeout problem? Absolutely.

The whole idea of a strike in baseball is that is a pitch that can be hit. The goal is to put the ball in play. That, in its original nineteenth-century conception, was how the game started. I realize that’s not the game we have. I enjoy the cat-and-mouse between batter and pitcher, and I’ll pump my fist and let out a shout at a particularly impressive or timely strikeout. I actually really enjoy seeing pitchers rack up impressive strikeout totals. Strikeouts are part of the game, but they are only part of the game. Per that last graph, we are well on our way to having a quarter of all plate appearances end in a strikeout. There were more strikeouts than hits in each of the last three seasons. Major League Baseball must do something to arrest and reverse this trend.

Two years ago, at The Athletic, I suggested raising the lower boundary of the strike zone. The idea is, strikeouts are made of strikes. If you want fewer strikeouts, step one is fewer strikes. Most of the strikes in the game today are at or below the bottom of the zone, so raising the strike zone’s lower limit would have an outsized impact on the number of strikes. Also, since 1996, the lower limit has been the hollow below the knee, but for all of major-league history prior to that it was the top of the knee. So, start there. Raise the bottom of the strike zone, and we can adjust further from there if (as will almost certainly be) necessary.

Transaction Reactions

Cardinals re-sign Yadier Molina ($9M/1yr)

If $9 million seems like a lot for a 38-year-old catcher who has posted an 85 OPS+ over the last two years, that’s because it is. Of course, this isn’t just any catcher, this is Yadier Molina signing up for an eighteenth year with the Cardinals. Molina is coming off a three-year, $60 million contract, so his salary for this season is falling by more than half and is analogous to what the Cardinals gave fellow legacy-scholarship-recipient Adam Wainwright ($8 million plus bonuses) two weeks ago. Still, I’ve always been a bit of a Molina skeptic. The Cardinals had an opportunity to upgrade behind the plate this winter, even if they didn’t want to spend big on J.T. Realmuto. Jason Castro and Wilson Ramos signed for $9 million combined, and Castro’s contract is for two years. You won’t convince me that St. Louis wouldn’t have been better off with those two for the same money. Fortunately for the Cardinals, the two teams that finished above them in the division last year, the Cubs and Reds, have largely punted this offseason, allowing the Redbirds to get away the sentimental move here.

Giants sign LHP Jake McGee ($7M/2yrs)

McGee was a valuable piece of the world champion Dodgers’ bullpen last year, rediscovering his Tampa Bay form after four years in Colorado. McGee throws almost nothing but fastballs. Seriously, per Statcast, McGee threw 332 pitches during the 2020 regular season; 320 of them were fastballs. That fastball sits consistently between 94 and 96 miles per hour, but McGee can vary the run on it, and that’s where the magic happens, in the movement and McGee’s extreme control of it. McGee faced 79 batters last year; he walked three of them, and neither hit a batter nor threw a wild pitch. The 34-year-old joins an almost comically left-heavy bullpen in San Francisco. Assuming Alex Wood will be in the rotation, the lefty relievers on the Giants’ 40-man now include McGee, Wandy Peralta, Jarlin García, Sam Selman, Caleb Baragar, and Conner Menez. McGee is by far the best of that lot and could wind up closing for the Giants if he can replicate his 2020 dominance.

Marlins sign OF Adam Duvall ($5M/1yr + $7M mutual option)

Duvall gives the Marlins a veteran alternative to the many young outfielders who have yet to pan out in Miami. He could prove to be the team’s primary left fielder, pushing Corey Dickerson over to right on a club that increasingly looks like a legitimate major-league team (and, yes, I know they won a playoff series last year; they were also just one game over .500 in a 60-game season). Duvall hit .248/.307/.545 with 26 home runs in 339 plate appearances with the Braves over the last two seasons, which stands as the best run of hitting in the former All-Star’s career. Per the Miami Herald’s Craig Mish, Duvall will make $2 million in 2021, and there is a $3 million buyout on his mutual option for 2022.

Mets sign IF Jonathan Villar ($3.55M/1yr) and CF Albert Almora Jr. ($1.25M/1yr)

These are depth moves for the Mets, who add a pair of youngish, athletic players who complement their roster nicely. Almora, who will turn 27 in April, is an ace flyhawk in any of the three outfield pastures and a useful bat against lefties. Villar, who will be 30 in May, can play on either side of second base, switch hit, and is a demon on the bases. Without a designated hitter in the NL this year, the Mets would have to put Jeff McNeil at second and Dominic Smith in left to get their best bats in the lineup. These two can caddy them in the field, and, where appropriate, against southpaws.

Angels acquire RHP Aaron Slegers from Rays for a player to be named later or cash

The 6-foot-10 Slegers is a low-velocity, low-spin sinker/slider guy who saw an encouraging jump in his groundball rate last year, a season in which everyone in the Rays’ bullpen seemed to finally find it. For an Angels team in constant need of pitching, it’s certainly worth a roster spot to see if he can repeat that performance over a full season.

Pedro Gomez (1962-2021)

Pedro Gomez died suddenly and unexpectedly on Sunday at the age of 58. Best known for his on-air baseball coverage on ESPN, Gomez wrote for numerous papers over a 35-year career, including the San Jose Mercury News, Sacramento Bee, and Arizona Republic. More important than any of his specific credits, however, Gomez was universally respected and beloved in our industry. I didn’t know Gomez, but I shared that respect. Beyond the quality of his writing and reporting, Gomez radiated a decency, warmth, and generosity that the tributes that rolled in upon the news of his death confirmed. I was particularly struck by Ken Rosenthal’s immediate reaction.

To that end, I wanted to share two twitter threads that speak to Gomez’s integrity and generosity. First, Howard Bryant’s tale of Gomez sticking up for a then-24-year-old Bryant in Tony La Russa’s office in 1993, which you can read here (warning: language). The words in Howard’s final tweet echo: “We lost a real one.”

Then this from ESPN’s T.J. Quinn, an account of how Gomez, writing for the Arizona Republic on the eve of Game 7 of the 2001 World Series, took Curt Schilling, the Diamondbacks’ Game 7 starter, to task in print, then made a point of making himself available on the field the next day to any player or team employee who wanted a piece of him. What resonates for me here, beyond that level of accountability and integrity, is Gomez’s reaction to the player who shook his hand. “Did you see that?!”

I didn’t know Gomez, but one thing that always stood out about him was a trait I’ve recently discovered that I value very highly: enthusiasm. Gomez earned the respect of everyone in the industry, but not by being dour and humorless about his work. He enjoyed what he did. He enjoyed the game, and he enjoyed the people in it. From what I saw of him on ESPN, he was always quick with a smile or a laugh. Though I didn’t know him, I choose to remember him that way.

By pure chance, the one interaction I had with Pedro Gomez can be found on YouTube. It, too, speaks to that joy that he took in what he did. The son of Cuban immigrants, Gomez was born in Miami less than a month after his parents arrived in the United States, a little more than a year after the Bay of Pigs invasion and two months before the Cuban Missile Crisis. As such, he grew up bilingual and was one of the few baseball reporters who could serve as his own translator with the major leagues’ growing Latin population. He would also, on occasion, serve as a translator for others.

My one interaction with Gomez came under such a circumstance. After Yoenis Céspedes won the 2013 Home Run Derby at Citi Field, Gomez served as his fellow Cuban’s translator in the postgame press conference. I was there covering the All-Star festivities for SI.com, with a particular emphasis on the Derby, and I got in an early question to Céspedes, which Gomez translated for me. I’ve queued up the following video to that question, but it’s a bit hard to hear me. What I asked was, “Yoenis, you hit 32 home runs in this Derby, which is tied for third all time with Canó and Ortiz. You also left five outs on the board when you hit that ninth home run in the finals. If you knew you were that close to that leader list, would you have kept going?”

In the video, while I’m speaking, Gomez is focusing on remembering the question to translate it, but you can see him smile when I mention the five outs that were left. He knows where I’m going, and he knows this could be a fun question. When translating, he cracks a smile again at “cinco outs.” Céspedes, to his great credit, nails the moment. He doesn’t equivocate or offer up a cliché. He responds with a single word that everyone in the room understands: “Sí.” It gets a bit laugh from Pedro and the room. Céspedes then adds a bit of explanation, a good tag. In Gomez’s translation: “Canó told me, once I hit nine, you can stop.” Again, Pedro’s having a ball. He’s up on that stage with the Derby champion, a fellow Cuban, he’s speaking Spanish, English, and baseball, and he’s fully engaged in the moment, enjoying every bit of it. I didn’t know Pedro Gomez, but I had that moment with him, and that’s how I’ll remember him.

Feedback

I want to hear from you. Got a question, a comment, a request? Reply to this issue. Want to participate in my reader survey (favorite team, place of residence, birth year)? Reply to this issue. Want to interview me on your podcast, send me your book, bake me some cookies? Reply to this issue. I will respond, and if I find your question particularly interesting, I’ll feature it in a future “Inbox.”

cyclenewsletter[at]substack[dot]com

Closing Credits

Today’s closing credits theme is “try,” something I wish more teams had done this offseason. There were many good options to choose from, including the rarely heard 1964 Rolling Stones original “Try A Little Harder,” Janis Joplin’s soulful “Try (Just A Little Bit Harder),” Sly and the Family Stone’s “You Can Make It If You Try,” and Marshall Crenshaw’s jangle-pop “Try,” but I’ve decided to go full cheese with the 1987 top-40 duet “Can’t We Try.”

Dan Hill was a Toronto-born soul singer and songwriter who had a number-three hit in the United States at the age of 23 with the deliciously maudlin “Sometimes When We Touch” co-written with Brill Building legend Barry Mann (Chorus: “Sometimes when we touch / the honesty’s too much / and I have to close my eyes and hide / I wanna hold you till I die / Till we both break down and cry / I wanna hold you till the fear in me subsides”). He continued to have success in his native Canada, but didn’t return to the American charts until nearly a full decade later, with the third song off his self-titled eighth album, a song he wrote with his wife, Beverly Chapin-Hill.

Like a surprising number of 1980s hits, “Can’t We Try” got a boost from its use in a daytime soap opera, in this case Santa Barbara. “Can’t We Try” is such a soap opera song. Like “Sometimes When We Touch,” it’s dripping with exaggerated earnestness, but this time, Hill has a duet partner: 24-year-old American actress and musician Vonda Shepard (whose name was misspelled, with two Ps, on the 45). Shepard is perhaps best known for her association with the hit ’90s show Ally McBeal. She also married noted producer Mitchell Froom and, as a result, is the stepmother of Suzanne Vega’s daughter.

Shepard’s entrance in this song actually reminds me a lot of Lita Ford’s on the Ozzy Osbourne duet “Close My Eyes Forever,” which only goes to show how pop metal and adult contemporary converged in the late ’80s. “Can’t We Try” was Billboard’s number-one adult contemporary song of 1987, and it sounds like it. The production is peak ’80s ballad, all chiming synth piano, mid-range bass, and echoing drums, immaculate, bloodless, some softly distorted power chords on the bridge, then back to the elevator music. There’s a false ending just after three-minutes that, shockingly, doesn’t cue a key change, but does launch the outro vamp, which reveals the shortcomings of Hill and Shepard’s voices.

Again, pure cheese, but, first of all, I unapologetically love ’80s cheese. Second, that cheese is what sells the relevant lines in the chorus for our purposes here. Hey, MLB general managers:

Caaaaan’t we try just a little bit harder?

Can’t we give just a little bit more?

. . .

Can’t we try just a little more passion?

Can’t we try just a little less pride?

Love you so much baby

That it tears me up in side

The Cycle will return on Friday with my grades for the teams in the Eastern Divisions.

In the meantime, let ‘em know: