The Cycle, Issue 5: Wardrobes Above Replacement

The middle 10 teams in my annual uniform rankings, Dustin Pedroia’s HOF chances, notes on allyship and collective bargaining, evaluating the Arenado trade, and more

In this issue of The Cycle . . .

My annual uniform rankings continue with the middle of the pack, teams 20 to 11.

Also:

Newswire: Why the players didn’t counter-offer; the lesson of the Mickey Callaway scandal

Major Laser: Dustin Pedroia’s Hall of Fame candidacy

Transaction Reactions: the details of the Arenado trade, Sean Doolittle is a Red, the Rays drop the mic on the Chris Archer trade, and more

Reader Survey

Closing Credits

Before we get started, word of mouth is very important to the growth and survival of The Cycle. Please spread the word, on social media and in person. Let people know how much you like The Cycle, and why they should sign up!

If you have any trouble seeing all of this issue on your email, you can read the entire issue at cyclenewsletter.substack.com. If you are already reading it there because you haven’t subscribed yet, you can fix that by clicking here:

The Cycle will be moving to paid subscriptions soon, but it remains free for now.

Watching the Clothes Go ‘Round: Annual uniform rankings, numbers 20–11

On Monday, I started my annual uniform rankings with the bottom ten teams. If you need the introduction to these rankings, you can find it there. Today, we continue with the middle ten, including three teams with identical alternate-jersey color schemes and one which has no alternates at all. The top ten will be in Friday’s newsletter.

I’ll spare you any further preamble, but I do want to repeat my note on the images and sources from yesterday:

The visuals below are all assembled from retail images, most of them from MLBshop.com. The caps are all photographs of actual caps (with the gold New Era sticker still on the bills), but the jerseys appear to have been created digitally on a template. In several cases, I did some additional photoshopping to increase the accuracy of a jersey (adding a missing patch or, quite often, the numbers). If the color of a cap doesn’t match the corresponding uniform, that’s due the difference in the sources and does not reflect an actual difference in the uniforms. In every case, if you are reading on substack, you can click to enlarge. Also, I want to give a blanket credit to UniformLineup.com and Chris Creamer’s SportsLogos.net, which were and are invaluable references for who wore what when, both within the 2020 season (UniformLineup) and over multiple seasons (SportsLogos).

Bring on the uniforms!

20. Cleveland Indians

Cleveland is one of three teams with identical alternate-jersey schemes. They, the Braves, and the Red Sox all have red alternates to their home whites and navy alternates to their road greys. All three have navy caps, and Cleveland and Atlanta both wear a red bill and button at home but an all-navy cap on the road. That lack of originality is a strike against all three. Still, all three are fairly handsome sets on their own merits, provided you can get past the Braves’ and Indians’ team names and Atlanta’s tomahawk iconography, which you needn’t do. Cleveland ranks last out of that trio bunch, but not because they are still using the team name they will discard after this season because it is racially insensitive (although that is not in their favor). Rather, it’s largely because they wear their alternates way to often and their worst jersey, the red home alternate, more often than any other. In 2020, they wore that red jersey 22 times, the blue 20, and the home whites, their best look on a purely aesthetic level, just seven times.

A word of warning: I’m going to bash the red jerseys of all three teams. I don’t have anything against red jerseys, as a rule. Red is actually my favorite color, and I like both the Angels’ red alternate and the Rangers’ red alternate (the latter divorced from the larger mess of Texas’s overall uniform scheme, of course). However, I do think it is hard to do a solid-red jersey well. The color is very aggressive, and it can very easily lean toward orange. Thus, I tend to bristle when teams that have blue as their primary color—which Cleveland, Boston, Atlanta, and Minnesota all do—trot out a red jersey.

Out of that lot, Cleveland has had the most success with red in the past. From 1965 to ’69, Cleveland wore a red cap and a vest over red sleeves, a look most closely associated with Sudden Sam McDowell and Luis Tiant. They brought back the red caps and red stirrups for a single year in 1972, and from 1974 to 1977, amid the explosion of color brought on by the move from flannel to polyester, they had a red jersey that they would pair, in the final three of those seasons, with red pants, a uniform that looked much better on Frank Robinson, Buddy Bell, and Dennis Eckersley than on Boog Powell. So Cleveland can do red, but this big blood clot of a jersey ain’t it.

Cleveland will have to redo at least its home uniforms when it adopts a new nickname for 2022, and the team could go as far as to adopt a whole new color scheme. At the very least, this will be the last season that we’ll see the two jerseys on the left above.

19. Washington Nationals

The Nationals were the most difficult team to rank this year. That’s because, last year, in all of their home games but the last, they wore the special, gold-trimmed uniforms at the far left above. Those weren’t so bad from the front, but the cap was pretty ugly, and the back of the jersey was a real eyesore with gold numbers and a clumsy double outline on the player names. However, those were celebrating their 2019 World Series win and won’t be worn going forward. These rankings are focused on what the teams wore last year, but I can’t bring myself to weigh that gaudy gold-trimmed look as heavily as I might another uniform that spanned, or will span, multiple seasons. Besides, there was a hidden benefit to the team’s devotion to that championship jersey: the Nationals didn’t wear any of their unbalanced, curly-W jerseys in 2020.

The Nationals adopted the curly-W jerseys in 2011. They weren’t terrible, but I could never get past the fact that the W on the left breast wasn’t even with the number on the right side (the Pirates’ current black home alternates have a similar issue, as mentioned on Monday). I also disliked the fact that the Nationals had so darn many of those jerseys. They started out with three in 2011: red-on-white, white-on-red, and a navy one that filled an inflated W with stars and stripes. In 2017, they added a stars-and-stripes-on-white version. That’s four W jerseys, all worn at home, to which they added the navy jersey above in 2018, giving them five possible home jerseys (the navy “Nationals” jersey is worn both home and road). That’s a mess, and it kept the Nationals in the bottom 10 in my standings. Trading those four curly-W jerseys for the gold-trimmed championship jersey was an upgrade, in my opinion, and I hold out hope that, this year, they’ll drop the gold and just stick with the three jerseys on the right above.

18. Atlanta Braves

Here’s Atlanta, looking a lot like Cleveland. Atlanta hasn’t gotten rid of its American Indian iconography, but it also strongly favors its home white over the red alternate (21 games to nine in 2020), the latter of which goes from bad to worse with that ugly, blue tomahawk. Regardless of the color, the tomahawk bothers me more each year. With Cleveland finally (if slowly) moving on from that imagery, it’s well past time for Atlanta to do the same. That’s only part of the reason that I’m disappointed that Atlanta didn’t wear its cream Sunday alternates last year. Since 2011, the Braves’ uniform set had included a cream alternate that dropped the tomahawk and used a single line of navy piping instead of the red outlined in navy. It was a throwback to their 1963–67 look, which straddled their move from Milwaukee to Atlanta and seemed to point a way forward to a tomahawk-free future for Atlanta’s uniforms.

A more radical change, which gained some steam in the wake of Hank Aaron’s passing, would be to rename the team the Hammers, in honor of Aaron’s nickname, and to replace the tomahawk with a similarly-designed hammer. That’s not a new idea. You can buy t-shirts, hoodies, and baby onesies with a mocked-up Hammer logo using the kind of hammer you might find in your toolbox. The best version of the Atlanta hammer I’ve seen, however, was part of this redesign proposal (which I don’t particularly care for beyond the hammer design) by Uni-Watch.com reader Jackson Morehead. Morehead’s design shows a hammer made of the head of a sledge-hammer tied to the end of a baseball bat. That design both motivates the retention of the rawhide straps in the logo but also gets to the heart of the idea that Atlanta’s hammers are their bats. It’s brilliant, and I’m sure someone with the Braves could do a better job of integrating it into their current look, which is a classic, but one better left to history.

17. Oakland Athletics

Speaking of redesigns that need to happen, it is way past time for the A’s to return to Kelly green full time. As nice as their home whites are, that Kelly-green alternate is so much better than anything they wear with the darker green, it’s no wonder they chose to wear it 22 times last year, including 16 times at home. Oakland should bring the Kelly green over to their home whites and road greys, ditch the second alternate, and wear the all-green cap (without the yellow outline), or their iconic yellow-billed cap, on the road. That would place them in my top five; it’s that easy. As it stands, the A’s not only wore the Kelly green more than any other jersey last year, they also deemphasized the forest green, which they wore more than 40 percent of the time in 2018 (67 times in a 162-game season), wearing it just nine times (four at home with the yellow-billed cap). Still, the clash of greens keeps Oakland mired in the middle of the pack despite all the other great things about this uniform, from its unique (for the majors) color scheme, to the wonderful elephant patch on the sleeve.

16. Cincinnati Reds

Speaking of patches, the Reds have a pretty fierce patch game between the full-body Mr. Redlegs on the home white and the Mr. Redlegs head on the red alternate. I even like the team-logo patch on the road jersey despite the fact that it largely echoes the cap logo (which is against my second rule of uniform clutter). I don’t love the red alternate, but Cincinnati limited it to Sundays and double-headers (both home and road, with the all-red cap at home). I could do without the drop-shadow, which is even more pervasive than it seems, extending to the home cap and within the logo on the chest of the home jersey. However, I have come around to the Reds’ use of black as an accent color on the road. I enjoy the fact that the city that was home to the first professional baseball team (which was not an ancestor of this franchise, but that’s another rant) is having fun with a nineteenth-century aesthetic in its fonts and mascot’s mustache and pillbox cap. Most importantly, the home uniform just looks great, even with the drop shadow (though it would look better without it). Add the simplicity of three jerseys and a clear home/road distinction for the caps, and the Reds just barely edge out what feels like a transitional set for the A’s.

15. Boston Red Sox

The Red Sox’s uniforms are the best of the three chromatically similar teams (see Cleveland and Atlanta above if you jumped straight here). The Sox largely eschewed the regrettable red alternate last year (just five games), they don’t have any problematic iconography, and their cap is so good they don’t need any variations on it. The sox sleeve patch is a great addition to the road greys and should be added to the navy road alternate (seriously, why is it not there?). The home uniform is a stone-cold classic dating back, in one form or another, to 1933. This is where we transition from good to very good on this list. If Boston ditched the alternate jerseys, this look would easily be in my top 10.

14. Philadelphia Phillies

Taken on their own, each of the Phillies’ four uniforms is very strong. The alternates are both throwbacks. The powder blue is an exact reproduction of their 1973–88 roadies (though the sleeve patch narrows that down to ’84–88). The cream, which is worn on Sundays, is an update on their 1946–49 look. For the standard home and road unis, the sleeve numbers are unique and a great detail, as are the corresponding blue stars in the wordmark and blue button on the caps (which were not a part of the original uniforms which inspired them). There is a lot to like here, but there are also some problems.

The biggest one is the powder-blue violation of wearing that old roadie at home, which is the only place the Phils wear it, though they do limit it to Thursdays (plus one double-header last year). That ’80s throwback is additionally problematic because the maroon clashes with the red of the rest of the set and gives the team a sort of confused identity similar to what the Brewers had prior to last year when they would alternate between their stalk-of-wheat logo and their ball-in-glove logo. Also, the home whites and road greys date back to 1992, and the font used for the number and player name, as well as the sleeve stripes on the road grey, are feeling a little dated. That said, as fond as I am of the team’s look in both eras, I still prefer this update to their 1950–69 look to the 1970–91 maroon set.

13. Milwaukee Brewers

Speaking of updates, the Brewers finally let go of the stalk-of-wheat (barley?) look last year and went with a full update of a two of their classic uniforms. I didn’t mind the barley design, but when you have something as good as that ball-in-glove logo (it’s an “m” and a “b” for those who never noticed, and there’s always someone who hasn’t noticed), you have to stick with it. The latter is one of the great sports logos of all time, and the Brewers brought a lightly updated version back full time last year for their 50th anniversary as part of their new kit, which updates their ’70s and ’80s home uniforms and adds a couple of new road looks.

Having grown up with Robin Yount and Paul Molitor in Brewers pinstripes, I like that update of the ’78–89 home uniform (worn 15 times last year), but I love the cream update on the ’72-77 uniform that Hank Aaron wore (worn 14 times last year). The Brewers also went the extra mile to design two new patches: a baseball with barley seams on the home jerseys, and a bricked-up Wisconsin (with a baseball in the correct location for Milwaukee, Rangers) for the road jerseys. Wearing cream during the week, pinstripes for weekend series (Friday to Sunday), and both in double-headers, the Brewers look awfully sharp at home.

I’m less enthused about the road options. The grey is fine, but the navy, worn 17 times to the grey’s 14 last year, looks like a college jersey. Some people like that; I don’t. The navy alternate also tries to have it both ways on the wordmark by using a script that incorporates block serifs that echo the other jerseys. It just doesn’t work for me at all. I actively dislike it, and, as much as I appreciate the return of the yellow-front road cap (previously worn 1974–85), I think it makes that jersey look even more amateurish. Drop the navy alternate and wear the yellow-front cap with the road grey (or, go all the way and turn that road grey into a powder blue), and this set is an easy top 10.

12. Kansas City Royals

That’s a lot of jerseys for this high in the rankings, and there’s a powder blue that they wear at home. However, the Royals, like the Rays, do the home powder-blue correctly, pairing the powder-blue jersey with white pants. No violation there. The gold-trim jersey is a relic from Kansas City’s championship celebration in 2016, but the Royals get away with it because they have gold in their logo. They are the Royals,after all, even if we will never be. Kansas City limits the gold trim to Friday home games. The powder blue is for Sunday home games. The royal-blue alternate is for Sunday road games. Those alternates are all well within bounds for the Royals’ overall look. Plus, they still play the vast majority of their games (more than 70 percent in 2020) in their standard home whites and road greys, which are just gorgeous and, despite many variations over the years, have been, since 2006, almost identical to the uniforms the franchise broke in with in 1969.

11. Detroit Tigers

The Tigers and Yankees are the only two teams in the majors without an alternate jersey, and there is a great deal of history in both uniforms. The Tigers have had an Old English D on their home jerseys for most of their history and combined it with placket piping for the first time in 1934. The script on the road jersey dates to 1930 (though the road-only use of orange only dates to 1972). On pure aesthetics, the road cap rivals the Twins’ gold-free TC cap for the title of the best in baseball (and the home cap isn’t far behind). I only have two notes here: First, the double outline on the road uniforms is unnecessary; drop the white (and maybe the number on the front, as well). Second, the team changed the D on the home jersey in 2018 to match the one on their cap. I understand why, but I’m still not used to it. The old jersey D pre-dated the current cap logo by decades and had been largely unchanged since 1908. I wouldn’t want to change that D on the cap, but adding it to the jersey undermines the legacy of the home uniform. Those two complaints keep Detroit out of the top 10, but just barely.

Newswire:

Players reject offer, Freedman offers insight

On Monday, as expected, the Players’ Association rejected the owners’ offer of a delayed, 154-game season with full pay but expanded playoffs. You can find more detail on the offer and the players’ objections in Monday’s newsletter, but I wanted to share an insight about the lack of a counter-offer from the union that Eugene Freedman, a baseball writer and labor lawyer, shared on twitter Monday night.

The gist of Freedman’s thread is that the structure of the season is already governed by the collective bargaining agreement and not subject to additional bargaining during the term of the agreement. By making offering to make changes to the schedule, the owners are, in effect, asking the players to open the agreement to renegotiate those parts touched on by the offer. The players are not required to do so, they already have an agreement in place, but if they make a counter offer, that represents an implicit agreement to open the agreement to renegotiation on these issues. Once those negotiations are open, a failure to reach agreement could allow the owners to implement their preferred terms unilaterally, as commissioner Rob Manfred did last summer in implementing the 60-game schedule. Thus, the players are rejecting the owners’ offer without countering so as to avoid reopening the agreement, as they would be happy to play the season under the standard rules already in place.

That last increasingly seems like the most likely outcome for the 2021 season. The only question, then, is what becomes of the various “new rules” that were in place last year, specifically the universal designated hitter, seven-inning double-header games, and the automatic runner on second base in extra innings. That remains to be seen, but the players’ choice not to counter the owners’ offer has a very specific legal motivation.

Incidentally, if you don’t follow Freedman on twitter, do so. He’s not only incredibly insightful on these matters, but he seems like an all-around good dude.

Callaway revelations expose failed allyship

An article in The Athletic on Monday detailed current Angels pitching coach, and former Mets manager, Mickey Callaway’s pattern of harassment of female members of the media. I suppose one could classify his behavior as aggressive flirting, but I’ll skip the details; there are plenty in the article. However you categorize it, Callaway’s behavior occurred over a period of at least six years, spanning his time with Cleveland, the Mets, and the Angels, and was entirely inappropriate, particularly in a work environment with a power dynamic as skewed as that between the press and the people they cover. The Angels suspended Calloway Tuesday afternoon, promising to collaborate with Major League Baseball on an investigation, but they should have relieved Callaway of his job immediately, and I hold out hope that the organization will ultimately come to that realization.

As disappointing and disturbing as Calloway’s behavior has been, however, there was a running theme in the descriptions of the reporters’ experiences with him that I found equally disturbing. Time and again, the article mentions that the women Callaway harassed were “warned” about Calloway by colleagues, and that that Calloway’s inappropriate behavior toward women in the workplace was “the worst-kept secret in sports.” I don’t know if those warnings came from other women on the beat or from some men, as well, but, either way, the information was heading in the wrong direction. Rather than warning potential victims (or, at least, in addition to warning potential victims), those who knew of Callaway’s behavior should have been reporting it to his superiors, and those superiors should have been taking it seriously and acting to stop it by taking concrete action against Callaway up to and including firing him.

This is especially true if those issuing the warnings were men. The recent revelations about Callaway and former Mets general manager Jared Porter make clear the fraught environment women covering baseball are forced to navigate. The men in our industry need to be better allies to the women in our industry. If we are aware of behavior like this, no matter its severity, we need to act, not just to warn the women, but to stop the offending men. There should be no tolerance for any sexualization of the relationship between team employees and the media. When it happens, it needs to be stopped, both in the moment and in general, and the men who dominate this industry (at least in number) need to take action to stop it.

I have no doubt that there are more Mickey Callaways and Jared Porters in baseball. I just hope the next time one is outed, it’s not because the women he harassed had to come forward, but because their colleagues said something to those in power, and those in power did something.

From Keystone to Cooperstown: Dustin Pedroia’s Hall of Fame case

Longtime Red Sox second baseman Dustin Pedroia announced his retirement on Monday. The 37-yeaer-old Pedroia had one year left on the eight-year extension he signed in July 2013, and he will still receive his $12 million salary for the coming season, but he had been limited to just nine games over the last three seasons by the deterioration of his left knee. Monday’s announcement was little more than Pedroia copping to the obvious: his body just won’t let him play anymore.

Because Pedroia has been sidelined for so long, it can be easy to forget just how good a player he was, and how great his career was, even if it was cut short by injury. The American League’s Rookie of the Year in 2007 and Most Valuable Player in 2008, Pedroia was the best all-around player on some impressive Red Sox teams and was central to their championship runs in 2007 and 2013. In truth, Pedroia has a very legitimate case for induction into the Hall of Fame. He’s far from a slam dunk, and may ultimately be left out, but he’s a candidate the voters (which hopefully will include me by the time Pedroia hits the ballot in 2025) will have to take very seriously.

The easiest way to illustrate Pedroia’s legitimacy as a Cooperstown candidate is to compare him to the Red Sox second baseman who is already in the Hall of Fame, Bobby Doerr. Here’s a quick side-by-side comparison of their careers:

*award shares, per Baseball-Reference’s calculations, based on portions of the vote received, not necessarily awards received

Doerr missed his age-27 season while serving in World War II. Credit him for that season, and he surpasses Pedroia in WAR and JAWS. It’s pretty obvious that Doerr had the better career, he saw more action, collected more hits, hit for more power, made more than twice as many All-Star teams, and edges Petey in the advanced stats, if you correct for that missing season. Still, it’s pretty close. They were obviously very similar players with similar-length careers. They were similar hitters, both excellent fielders, and both played the same position in the same home ballpark for the same team, just a half-century apart. Most importantly, Doerr is in the Hall of Fame. It took him until 1986 and a Ted Williams-led Veterans Committee to get in, but he’s far from a regrettable selection.

Pedroia and Doerr both fall short of the JAWS standard for second basemen, which is 57.0. However, of the top 24 second basemen, per JAWS, who are already Hall-eligible, 18 are in, and the six exceptions include notable snubs such as Bobby Grich, Lou Whitaker, and Willie Randolph. Of the 18 that are in, five rank below Pedroia in JAWS, including Doerr, Nellie Fox, and Yankee great Tony Lazzeri, though it’s worth noting that those three were all Veterans Committee inductees.

The most relevant conversation to have with regards to Pedroia’s candidacy, however, may be one that compares him to his contemporaries. We’re deep enough into the twenty-first century that we can use the turn of the millennium as a dividing line. Limiting our scope to the new century, four second basemen stand above the pack. Of those four, Robinson Canó stands apart as both obviously Hall-worthy in terms of his accomplishments and obviously compromised due to a pair of positive performance-enhancing drug test, one in 2018 that detected a masking agent, and one this past November, for the steroid stanozolol, resulting in his suspension for the entire 2021 season.

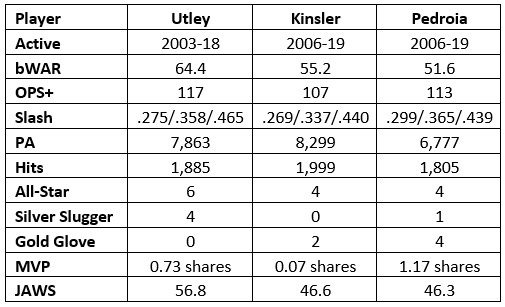

The other three exceptional second basemen of the new century are Chase Utley, Ian Kinsler, and Pedroia. Here’s the side-by-side for that trio:

Utley is right at the JAWS line, but before we get to him, let’s compare Pedroia and Kinsler. Both were athletic, all-around contributors who won, and deserved, multiple Gold Gloves, made four All-Star teams, participated in multiple World Series, and mostly played in the same league over the same 14 seasons. Kinsler stayed healthier, coming to the plate more than 1,500 more times than Pedroia, the equivalent of more than two full seasons. Yet, despite that playing-time advantage, Pedroia is right there with Kinsler in terms of the cumulative wins-above-replacement stats (bWAR and JAWS). Pedroia also edges Kinsler by a fair margin in the park-adjusted OPS+ as well as in his raw batting line. Given Pedroia’s edge in those categories, as well as in awards and honors (Kinsler, inarguably underappreciated, never finished higher than 11th in the MVP voting), I feel confident saying that Pedroia was the better player and had a better career than Kinsler.

That leaves Pedroia alone against Utley for the title of best non-Canó second baseman of the new millennium. Here, Utley’s playing-time advantage is smaller and his wins-above-replacement advantage is much larger. Utley didn’t win any Gold Gloves, but he was a Gold Glove-worthy fielder, as much due to excellent positioning as athleticism. Utley also hit for much more power than Pedroia and edges him in OPS+, Silver Sluggers, and All-Star appearances (though it is worth noting that there was less competition for second-base honors in the NL during their careers than in the AL, which had Canó, Pedroia, Kinsler, and, in the 2010s, José Altuve, who could complicate this conversation if he rebounds from last year and remains productive well into his thirties).

Utley was clearly better than Pedroia, but I also think Utley is clearly a Hall of Famer. His will be an interesting candidacy. As JAWS inventor Jay Jaffe often points out, “Neither the BBWAA nor the various small committees has elected a position player with fewer than 2,000 hits whose career crossed into the post-1960 expansion era, no matter their merits.” None. Not one.

Perhaps Andruw Jones (1,933 career hits) will be the first. He’s certainly trending in that direction. Perhaps Utley will join him after he reaches the ballot in 2024, a year ahead of Pedroia. Still, Utley’s 1,885 career hit seem like they could be a difficult obstacle to overcome for a player that was perceived as being bat-first, even if that perception was inaccurate. Pedroia was more recognized for his fielding (how could you not notice the way he would fling his tiny body into shallow right field to make a play), but his 1,805 hits it could make his already borderline case all the tougher to make.

Still, it’s a case worth making. Pedroia got more out of his (allegedly) 5-foot-9 frame than anyone thought possible. He was a Rookie of the Year and MVP. His best year came three years after the latter award, an eight-win season in which he hit .307/.389/.474 (131 OPS+) with 21 homers, 26 stolen bases, and won the Gold Glove. He was a key player on two Red Sox championships (2007 and ’13), the little engine that made so many powerful Boston teams go both on the field and in the clubhouse.

I’ll admit to being something of a big-Hall guy. Still, I could see myself checking the box for Pedroia if there’s room on my ballot in 2025. The Hall of Fame could do worse than to count him among its members.

Transaction Reactions

Cardinals acquire 3B Nolan Arenado and cash considerations from the Rockies for LHP Austin Gomber and minor leaguers 3B Elehuris Montero, SS Mateo Gil, and RHPs Tony Locey and Jake Sommers

The Nolan Arenado trade became official on Monday. I wrote about the player the Cardinals are getting in the last issue of The Cycle, so let’s focus here on the other aspects of the trade. There are two main components here: the five-player package the Rockies are receiving from St. Louis, and the various considerations with regard to the terms and value of Arenado’s contract. The latter is the more significant, and goes a long way toward explaining why the former is so insignificant, so let’s start with the contract.

In February 2019, the Rockies signed Arenado to an eight-year, $260 million extension that, at the time, was the eighth-largest contract in major-league history (it is now 14th, having been surpassed by Bryce Harper, Stephen Strasburg, Anthony Rendon, Gerrit Cole, and Mookie Betts). That contract included an opt-out after the 2021 season, which, with the Rockies languishing near the bottom of the National League West in recent seasons, was a key motivating factor for the decision to trade Arenado now.

Heading into this season, the Rockies still owed Arenado $199 million over the next six seasons, not counting the various awards-based bonuses included in the pact. He also had a no-trade clause, which allowed him to leverage the Cardinals for adjustments to his deal. To get Arenado to waive his no-trade clause, the Cardinals added an extra year to the contract, agreeing to pay Arenado $15 million for the 2027 season and thus increasing his remaining guarantee to $214 million over seven years. They also added a second opt-out after the 2022 season. As a result, this fall, after his age-30 season, Arenado will have a choice between the potential spoils of free agency or the six years and $179 million remaining on his deal with the Cardinals. If he doesn’t opt out this fall, next fall, after his age-31 season, he can choose between free agency and the remaining five years and $144 million.

Meanwhile, in order to try to make this something more than a salary dump and to get some half-way decent players in return, the Rockies have agreed pay Arenado’s entire 2021 salary of $35 million ($20 million of which will be deferred), plus another $16 million of what remains on his contract if he does not opt out. From the Cardinals’ perspective, that means they could have Arenado for the next seven years for $163 million (an average annual expense of roughly $23.3 million), they could have him for two years at roughly $35 million (it’s not clear how much, if any, of that extra $16 million from Colorado would go toward Arenado’s 2022 salary), or they could have him as a one-year loaner without having to pay him a dime (other than those awards bonuses, which I’m sure they’d happily pay).

From the Rockies’ side of things, if Arenado wasn’t going to opt out of Colorado in the fall, they just saved $148 million over the next six years. However, if he was going to opt out, they just spent an extra $16 million for five non-prospects and the privilege of watching Arenado play what should have been his final year in Colorado for another team. Unless, of course, Arenado still opts of St. Louis in the fall, in which case they still get the non-prospects and to watch Arenado play for another team, but they didn’t pay extra for the privilege, only what they already owed Nolan.

You can see why I avoided writing about this until these details were finalized.

I’ve already tipped my hand here, but that opt out is why the Cardinals didn’t give up any particularly notable talent in this deal. Of the five players the Rockies are receiving, lefty Austin Gomber is the only one who has reached the majors. He is a 27-year-old former fourth-round pick who had some small-sample success for the Cardinals last year after making his debut in 2018 and spending 2019 back in the minors while battling injuries. The 6-foot-5 Gomber throws a fastball/curveball/slider mix with average velocity and induced a bit more than his share of groundballs last year. He’s most likely swing-man material with a ceiling of being the next J.A. Happ. That’s not nothing, but, again, he’s already 27 and he’s heading to Coors Field. None of the other four players heading to Colorado earned a mention when Baseball Prospectus listed the Cardinals’ top 10 prospects (plus four honorable mentions) last week.

Here are some quick takes on those four:

Elehuris Montero is on the 40-man roster. The 22-year-old is a big, Dominican third baseman who struggled mightily upon reaching Double-A in 2019, in part due to wrist injuries. Last year, he was one of the Cardinals who caught COVID-19, and he spent the healthy portion of his season at the Cardinals’ alternate training site. Baseball Prospectus did rank Montero tenth among Cardinals prospects a year ago, touting his significant power at the plate, but that is undermined by his struggles to make contact. Also, his size and waning athleticism may force him to move to move to first base.

Mateo Gil is a shortstop whom the Cardinals drafted out of a Texas high school in 2018’s third round. Now 20, he has played just two games above rookie ball. Consider him a lottery ticket.

University of Georgia product Tony Locey was the Cardinals’ third-round pick the year after Gil. Locey made 12 relief appearances in the low minors after signing, but did not play last year. He is now 22 and projects as a fairly generic reliever: a sinker/slider righty who throws in the mid-90s with control issues.

Finally, Jake Sommers, an average-sized righty, was drafted out of the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee in the 10th round in 2019. He didn’t get above rookie ball that season, was inactive last year, and will turn 24 in May.

Don’t look for any of those five to have an impact on the Rockies this year or in the future. Meanwhile, do look for a big rebound/quasi-walk year in St. Louis from Arenado, who will likely bat behind Paul Goldschmidt in the lineup and lock Tommy Edman into second base while top prospect Dylan Carlson roams the outfield. In addition to adding Arenado and recently re-signing Adam Wainwright, according to MLB Network’s Jon Morosi, the Cardinals are expected to come to terms on a one-year deal with Yadier Molina after the conclusion of the Caribbean Series this weekend.

Angels acquire RHP Alex Cobb and $10 million for 2B Jahmai Jones

Once a well-regarded groundballer with the Joe Maddon-era Rays, Cobb had a nice walk year in 2017 and, in March of 2018, signed a four-year, $57 million contract with an Orioles team on the verge of total collapse. In his first year with Baltimore, the O’s lost 115 games and Cobb went 5-15 with a 4.90 ERA. The next year, he was limited to just three starts by a femoroacetabular impingement in his right hip that required surgery. Healthy again in 2020, he bounced back nicely, spiking his groundball rate and churning out a league-average performance over 10 starts. Seeing an opportunity to cash in the final year of his deal, the O’s are sending him to the pitching-hungry Angels and paying two thirds of his salary in exchange for 23-year-old Jahmai Jones, who dented the bottom of the major prospects lists prior to the 2018 season but saw his stock fall between that and his 3-for-7 performance in his first major-league opportunity last year.

Jones has never played at Triple-A, but he’ll get a shot at the Orioles’ open second-base job in camp. He hasn’t hit much since reaching Double-A for the first time in 2018, but he’s athletic, young enough, and started out as a centerfielder, so there’s some utility potential here, as well.

As for the Angels, if Cobb is healthy, he could well be worth the $5 million and a faded prospect they’re paying for him (especially given that some of that $5 million will reportedly be deferred), but he’s yet another middling starter on a team that doesn’t feel any closer to a playoff berth.

Rays sign RHP Chris Archer ($6.5M/1yr)

It’s clear by now that the Rays won the 2018 deadline deal that sent Archer to the Pirates for righty Tyler Glasnow, outfielder Austin Meadows, and the Pirates’ first-rounder from the previous year, righty Shane Baz (Baz made three of this year’s major top-100 prospects lists, topping out at 24th on Baseball Prospectus’s top 101). For the Rays to now swoop in and re-sign Archer almost feels like rubbing it in.

Archer arrived in Pittsburgh in late 2018 with a team-friendly contract that made him controllable for just $27.5 million over the next three years via a pair of club options. The Pirates didn’t even get one full season out of him. He managed just 119 2/3 innings in 2019 due to thumb inflammation and a shoulder issue that may have been an early indication of the thoracic outlet syndrome for which he had surgery last June. As a result of that surgery, Archer missed the shortened 2020 season entirely, and the Pirates declined his $11 million option for 2021. Now, Archer will see if he can piece himself back together with his old team at the age of 32. If healthy, Archer and his (formerly?) all-world slider will compete with Josh Fleming, Trevor Richards, free-agent addition Michael Wacha, and prospects Shane McClanahan and Luis Patiño for one of the last three spots in the Rays’ rotation this spring.

Cubs sign LHP Andrew Chafin ($2.75M/1yr + $5.25 mutual option)

From 2017 to 2019, it seemed as though every Diamondbacks game I watched included a relief appearance by Andrew Chafin. Chafin averaged 75 games per season over those three years with a robust strikeout rate and a 130 OPS+. Last year, he was limited to just 9 2/3 innings by shoulder tendonitis and a finger sprain. While he was on the injured list, Arizona flipped him to the Cubs at the trading deadline for a teenage second baseman who has yet to see action outside of his native Dominican Republic. Chafin made four solid relief appearances in late September, then hit free agency. The Cubs are hoping he can recover his pre-2020 form, though he’d be even better if he could show improved control as well.

Reds sign LHP Sean Doolittle ($1.5M/1yr + performance bonuses)

By all accounts, Sean Doolittle is one of the most genuinely decent human beings in baseball. Drafted late in 2007’s first round as a first baseman, he switched to pitching in 2012 and built himself up into a closer, an All-Star, and eventually a world champion with the Nationals in 2019. A thoughtful, charismatic man, he is active in the community and online, funny, self-deprecating, considerate, socially responsible, and generally very easy to root for. That made his struggles last year all the tougher to take.

It was just 7 2/3 innings, and he had issues with his right knee (landing leg) in the middle of it before a season-ending oblique strain shut him down. Still, he’s a pitcher who throws more than 80 percent fastballs whose velocity has been in decline for four straight seasons and took a big dip last year, from an average of 93.5 miles per hour in 2019 to just 90.7 mph. That knee is a source of genuine concern. Knee injuries are what prompted his transition to pitching a decade ago. He’s now 34, will be 35 in September, and he hasn’t followed a healthy season with another since 2014. Still, the Reds are taking an affordable gamble on a pitcher who, if healthy, could succeed the departed Raisel Iglesias as closer, though he’s more likely to set up righty Lucas Sims or fellow lefty Amir Garrett.

Mets acquire RHP Jordan Yamamoto from Marlins for minor-league IF Frederico Polanco

The Christian Yelich trade hasn’t gone well for the Marlins. By that I mean, it has gone even worse than expected. Lewis Brinson looks like a bust; he’ll be 27 in May and has a career OPS+ of 48 after 821 major-league plate appearances. Monte Harrison looked completely overmatched in his debut last year, striking out 26 times in 51 plate appearances and making weak contact; he’ll be 26 in August. That leaves second baseman Isan Díaz as Miami’s best hope for some kind of payoff, because the fourth prospect in the deal, righty Jordan Yamamoto, is the first on which the Marlins have cut bait.

Yamamoto looked like a promising mid-rotation prospect as a rookie in 2019, but his 2020 was a mess. His already sub-par velocity was down, he got lit up, farmed out, then coughed up a whopping 13 runs in a single relief appearance in September. Miami designated him for assignment to make room for free-agent reliever Anthony Bass. The Mets will take a flier to see if the Hawaii native can recover his 2019 form. As for Polanco, he’s an undersized 19-year-old Dominican utility infielder with just 14 games of experience in the States.

Reader Survey

In order to serve you better, I would like to know a little more about you. This is optional, of course, but, if you don’t mind, please reply to this issue with:

your favorite team (or teams, or if you are a general-interest baseball fan)

your general location (as many of the following as you feel comfortable sharing: city, state, province, country for those outside the U.S. and Canada)

your birth year (because it doesn’t change, unlike your age)

The idea here is to know whom I’m writing for, what teams you want to read about, and when and where you’ll receive the newsletter. I can’t promise I’ll write more about the Orioles if you tell me you’re a Orioles fan, but if there’s a large Orioles contingent among the readership, I will likely lower my threshold for including Orioles items and dive deeper into the ones I include.

Closing Credits

I didn’t write all that much about Dustin Pedroia’s personality above, but that was a significant part of his presence in the game at the height of his career. One particularly entertaining running gag was the way that Pedroia and his manager, Terry Francona, would relentlessly rag on each other, both in private and for show, such as during pre-, post-, and in-game interviews. They were like a comedy duo, with haircuts (both men were mostly bald) and card games central to the trash talking. The difference between the two, however, was that Francona was always very obviously kidding. Pedroia had more of a game face and it sometimes was difficult to tell when he was pretending to be a jerk or if he sometimes tripped over the line to becoming one.

One memorable incident in which he clearly was trying to lift the mood was when he effectively gave himself the nickname “Laser Show.” It happened during a post-game interview in early May of 2010. David Ortiz was off to an awful start that season, hitting just .143 in April and still languishing at .182 on the day of the interview. In defending his teammate, Pedroia pointed out his own struggles early in his Rookie of the Year season of 2007 (Pedrioa hit .172 through his first 58 at-bats of that season).

“It happens to everybody, man,” Pedroia said. “He’s had 60 at-bats. I mean, a couple of years ago I had 60 at-bats, and I was hitting .170, and everyone was ready to kill me, too. And what happened? Laser show.”

Pedroia tries to deliver the line straight but can barely suppress his smile during the exchange (one writer incorrectly identifies the season he was referencing as his MVP season of ’08). He remained “Laser Show” for the better part of that decade and lived up to the nickname for the most part, as intentionally ridiculous as it was. It thus seems fitting that I leave you today with a song with that exact title.

This is “Laser Show” from power-pop masters Fountains of Wayne. The song arrives late on the band’s 1999 sophomore effort Utopia Parkway. Utopia Parkway is a real road in Queens. Fountains of Wayne was a real store that sold fountains and other garden decorations on Route 46 in Wayne, New Jersey. I used to drive by it all the time on my way home from my band’s rehearsal space around the time that Fountains of Wayne the band released their third album.

The band’s songwriting duties were split between singer/guitarist Chris Collingwood and bassist/prolific pop genius and New Jersey native Adam Schlesinger, the latter of whom died from complications of COVID-19 last April at the age of 52. Though they always wrote alone, the two shared songwriting credit on every song, and I never tuned my ear to their albums enough to be able to sort out who wrote what (unlike John Lennon and Paul McCartney, who mostly sang their own songs on Beatles records, Collingwood sang everything for Fountains of Wayne). If I had to guess, I’d say this is a Schlesinger tune, but I don’t know for sure.

“Laser Show” has more than a little in common with Nick Lowe’s “Rollers Show,” Lowe’s unironic tribute to Scottish teen idols the Bay City Rollers (whose “Saturday Night” still slaps). In “Laser Show,” all the kids from Connecticut and Long Island are headed to the Hayden Planetarium at Manhattan’s Museum of Natural history to see the music of Pink Floyd and Metallica set to lasers, a stoner’s tradition that continues to the present day. My favorite part is when the lyrics call out the members of . . . And Justice For All-era Metallica as though they’re a boy band:

We’re gonna sit back, relax, and watch the stars

James and Jason, Kirk and Lars!

Someone on YouTube edited Wayne’s World footage to the song. It works.

The Cycle will return on Friday with my top 10 uniforms and, if time allows, more thoughts on the Arenado trade and a look at A.J. Preller’s tenure in San Diego (the Padres just extended his contract four years to 2026), among other things.

In the meantime, please help spread the word about The Cycle!