The Cycle, Issue 2: Future Hall of Famers

Parsing the Hall of Fame vote, thoughts on a delayed Spring Training and sticky baseballs, shortstop dominoes fall, the Yanks and Sox make a trade, and a puppy has a party

In this issue of The Cycle . . .

Just because no one was elected to the Hall of Fame doesn’t mean the results of the vote have nothing to tell us. I take you through the history of writers’-ballot shutouts and look at Tuesday night’s results to try to determine which players from this year’s ballot have the best hope of eventual induction.

Also:

Newswire: Cactus League requests delay, Sticky-stuff suit dismissed

Transaction Reactions: Realmuto signs, Shortstop dominoes fall, Yankees and Red Sox make a trade

Puppy Party

Reader Survey

Closing Credits

Before we get started, word of mouth is very important to the growth and survival of The Cycle. Please spread the word, on social media and in person, and let people know how much you like The Cycle, and why (I hope) you can’t wait for the next one!

If you have any trouble seeing all of this issue on your email, you can read the entire issue at cyclenewsletter.substack.com. If you are already reading it there because you haven’t subscribed yet, you can fix that by clicking here:

Hall of Fame Results: Every vote means something

Part I: You can still get a goose from a goose egg

As was widely expected, the Baseball Writers’ Association of America* failed to elect anyone to the Hall of Fame this year, according to the vote results announced on the MLB Network Tuesday evening. This marks just the ninth time in 77 years** of BBWAA voting that the writers threw up a goose egg, and the first since 2013.

*I am a member of the BBWAA, but still a few years away from my first Hall of Fame ballot

**there were nine years between 1940 and 1965 in which the writers did not hold a Hall of Fame vote

I remember being quite annoyed that the writers couldn’t get anyone over the 75 percent threshold required for induction in 2013. I’m less upset this year, but only because I’ve come to realize that a shutout this year doesn’t mean none of the players on this year’s ballot will ever get in. Quite the opposite, in fact.

The 2013 ballot, which yielded no Hall of Famers that year, included nine players who have since been inducted, six by the writers (Craig Biggio, Jeff Bagwell, Mike Piazza, Tim Raines, Edgar Martinez, and Larry Walker) and three by the Today’s Game Era Committee (Jack Morris, Lee Smith, and Alan Trammell). Four more players from that ballot (Curt Schilling, Roger Clemens, Barry Bonds, and Sammy Sosa) were still on the ballot this year, and will be again next year, their final year of eligibility. We’ll take a closer look at their chances in a moment.

As for the other six shutouts by the writers, all but the last two were the result, not of a lack of viable candidates or finicky writers, but an overabundance of viable candidates and the voting rules preventing the writers from being able to vote for enough of them.

The first shutout came in 1945, and it was an absolute mess. The writers had held a vote just once in the previous five years, electing just one player, Rogers Hornsby. As a result, the 1945 ballot was absolutely overrun with worthy candidates. That year, 95 different players receive votes, including Joe DiMaggio, who wouldn’t retire for another six years. A whopping 56 of them would eventually be inducted, but with a limit on the number of players any individual writer could include on their ballot, the lack of an obvious consensus doomed the process. The vote was so diffuse that Lefty Grove, retired for four years by that point, was named on just 11.3 percent of ballots and finished 26th in the voting. Every man in the top 33 that year has since been inducted. The same problem plagued 1946, another massive ballot loaded with future Hall of Famers (76 players received votes, 46 have since been inducted). Jimmie Foxx, who was active the year before, received 12.9 percent that year, finishing 26th. The top 28 vote recipients in 1946 have since been inducted.

You’d think the writers would have fixed the process by 1950, but no dice. That year, 100 players received votes, including 49 future Hall of Famers. Foxx was still on the ballot; he finished third with 61.3 percent. No one got the required 75 percent. The BBWAA was more productive in the 1950s, but, in 1956, the Hall decided the writers should only vote in even years. After taking 1957 off, the writers’ ballot in 1958 was perhaps the biggest mess yet. A whopping 154 players received votes that year. Only Max Carey was named on more than half the ballots; he got 51.1 percent of the vote. Two years later, same problem: 134 players received votes, no one got more than Edd Roush’s 54.3 percent.

The next shutout wasn’t until 1971, and that ballot was far more reasonable. Still, it still suffered for the lack of the five-percent minimum, as 23 players returned to that ballot that year to receive less than five percent of the vote. In total, 48 players received votes in 1971, but this time just 15 would eventually reach the Hall of Fame. The top vote-recipient was Yogi Berra at 67.2 percent. Yogi Berra. This is worth bearing in mind for those who would like to eliminate the five-percent minimum so as to get multiple chances to consider players such as Kenny Lofton, Jim Edmonds, and Johan Santana, just to name three recent candidates who deserved better than to be one-and-done on the ballot. If there are too many players on the ballot, it makes such a mess that not even Yogi Berra can get elected. The better solution to the one-and-done problem is to remove the limit on the number of players each writer can select. That way, writers can throw a vote to a player they might want to keep from falling off without having to bump someone they consider more deserving off their ballot.

After 1971, you have to advance all the way up to 1996 to get another shutout. I remember that one. Phil Niekro, Tony Perez, and Don Sutton each fell between 63 and 69 percent, each inching their way toward eventual induction, but it was a genuinely weak ballot, overall. Jim Rice and Bruce Sutter were the only other players on that ballot who would eventually be elected by the writers, and both are borderline cases, as is Perez and, some would argue, Sutton. In addition to those five, only two other men on that ballot have since gone in via the Eras Committees: Ron Santo, whose tragic candidacy is its own story, and Joe Torre, who would get the nod for the portion of his managerial career that he was only just starting in 1996.

There were plenty of other players on that 1996 ballot that have strong cases for Eras Committee induction—among them Dick Allen, Minnie Miñoso, Luis Tiant, Tony Oliva, Jim Kaat, Tommy John, and Keith Hernandez—but they remain on the outside looking in 25 years later.

The point of all that history is that, of those nine shutouts, the 1996 ballot contained the fewest future Hall of Famers, and it still had seven of them. I hold out hope that others from that ballot will join them, Miñoso especially. So, while none of this year’s candidates were elected, you can be sure there are future Hall of Famers on that ballot. Who are they? Let’s take a closer look at those results . . .

Part II: Finding this year’s future Hall of Famers

Proceeding in rough order of this year’s finish, and grouping comparable candidacies where applicable, we start with three candidates who are their own worst enemies:

Curt Schilling, Barry Bonds, and Roger Clemens

This year’s top vote recipient was Curt Schilling, who was named on 71.1 percent of the ballots, falling just 16 votes shy of induction in a year that a record 14 writers returned blank ballots. For most players, coming that close would mean guaranteed election the next year, but Curt Schilling is a unique case. As are Bonds and Clemens, who continue to move in unison, this year finishing second and third with 61.8 and 61.6 percent, respectively (Bonds, who had finished ever so slightly behind Clemens in all eight of their previous years on the ballot, received one more vote than Clemens this year).

All three will appear on the writers’ ballot for the final time next year. Here’s how their candidacies have progressed to this point:

Bonds and Clemens clearly don’t have the trajectory to get in. Schilling was well on his way in 2016, but that dip in 2017 came after he endorsed the idea of lynching journalists. Many writers have since found the ability to forgive him, but that forgiveness may have reached its limit. Last year, Schilling was just 20 votes shy of induction. This year, he was still 16 shy, and if the votes had been cast a week later, he likely would have lost support.

As always, this year’s voting deadline was December 31. On January 6, Schilling came out in profane support of the insurrection at the Capitol Building, causing many who voted for him to regret doing so. He’s still close enough that he could sneak in on his final ballot, but it seems more likely that he’ll experience another blowback, like he did in 2017, and fall short.

These three are all tragic cases. Bonds and Clemens were clearly inner-circle Hall of Famers before they polluted their legacies with performance-enhancing drugs. The change in their vote share over the years hasn’t been the result of voters changing their minds about Bonds and Clemens. It has been about the voters changing their minds about PED use, and the ceiling those two appear to be hitting could give us an idea of what to expect when Alex Rodríguez hits the ballot for the first time next year.

Meanwhile, the writers seemed to consider Schilling a borderline case when he first hit the ballot in 2013, but I think there is now a consensus that his career was Hall of Fame worthy. However, there is a very understandable reluctance to amplify his voice via a Hall of Fame induction. His inability to keep his racist, seditious, and violently un-American thoughts to himself will most likely cost him what, five years ago, appeared to be a sure thing.

Scott Rolen, Omar Vizquel, Andruw Jones, and Todd Helton

I’ve grouped these four together because they all appeared on the ballot about the same time—Rolen, Vizquel, and Jones in 2018, Helton in 2019—and they have all had encouraging results in their short time on the ballot.

Here are their trajectories:

One of these things is not like the other, and that’s Vizquel. Vizquel debuted with 37 percent of the vote in 2018, and his support grew from there, but domestic violence charges cut into his support this year. Vizquel received just a dozen fewer votes this year than a year ago, but advanced analysis does not support his candidacy, and one wonders if his off-field behavior might reveal his candidacy to be a house of cards.

Far more encouraging are the trajectories of Rolen, Helton, and Jones. I was very disappointed by the weak first-year support Rolen and Jones received, but it appears the writers as a whole are quickly, and correctly, coming around to their candidacies. Helton is right there with them with an extra year of eligibility.

Rolen, already over 50 percent with six years to go, now looks like a lock to get in. Helton, at 44.9 percent with seven years to go, looks likely to follow fellow Rockies great Larry Walker into the Hall now that the writers seem to have figured out how to adjust for Coors Field without simply writing off what those players accomplished there. Jones is a little further behind, but his trajectory is the same as Rolen and Helton. He may take a year or two longer to get there, but with six years left, Jones has the time.

I should note here that that the lack of strong first-year candidates this year made room on many ballots for players like Rolen, Helton, and Jones, who were often mentioned as eleventh men on more crowded ballots (voters can vote for no more than ten in any given year). However, the ballot will remain thin for a few more years. The big additions next year will be Rodríguez and David Ortiz, the latter of whom has a chance of immediate induction. In 2023, Carlos Beltrán arrives, but Bonds, Clemens, Schilling, and Sammy Sosa fall off. In 2024, Adrián Beltré, Joe Mauer, Chase Utley, and David Wright are added, but Jeff Kent leaves. There’s some runway there for players like Rolen and company to get right up to the doorstep of induction, if not all the way in.

Billy Wagner

Check this out:

His first three years on the Ballot, Wagner didn’t seem to be going anywhere. Then, he nearly doubled his support in 2020, and jumped another 15 points (actually 14.5) this year. He’s now at 46.4 percent—trailing only Schilling, Bonds, Clemens, Rolen and Vizquel on this year’s ballot—and appears to be rocketing toward induction.

What changed? Fellow closer Trevor Hoffman was elected in 2018, and Wagner actually compares quite well to Hoffman, with less longevity but a more impressive peak. In 2019, the Today’s Game Era Committee inducted Lee Smith, another National League closer the writers couldn’t quite get across the finish line. With those two in, Wagner suddenly feels like an omission, and his support is growing to reflect that. That said, Smith stalled out at 50.6 percent of the writers’ vote. With just four years left, Wagner can’t afford any backsliding. He should cross 50 percent next year. How he fares on the 2023 ballot could be crucial.

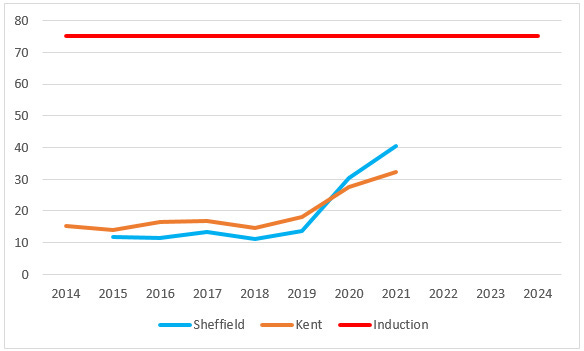

Gary Sheffield and Jeff Kent

It wasn’t long ago that Sheffield, Kent, and Wagner all seemed mired in sub-20-percent limbo, destined to play out their 10 years on the ballot with no actual hope of induction. All three have broken out of that space since, but only Wagner seems to be on a clear trajectory toward induction. Here’s how Sheffield and Kent, the latter of whom got to the ballot a year earlier and thus has just two years of eligibility left, are progressing:

With just two years left, Kent isn’t going to make it. Sheffield, who has three years remaining, is a long shot, but he has a chance. Sheffield crossed 40 percent this year, finishing between Andruw Jones and Todd Helton, two players who I now believe are future Hall of Famers. However, Sheff would need an average gain of more than 10 percentage points in each of his final three years on the ballot to cross the induction threshold. Larry Walker climbed even faster in his last three years, gaining more than 20 percent in each of his last two years of eligibility, so it can be done, but Sheffield is as well liked as Walker, whose candidacy was held back more by Coors Field and a sketchy injury history than by any other concerns. Sheffield was awe-inspiring at the plate, but he was a poor fielder, could be gruff with the media, and admitted to using performance-enhancing drugs during the 2004 BALCO scandal. My guess is he falls just short both on the writers’ ballot and on multiple Veterans Committee ballots in the future, but his is very much a candidacy to watch.

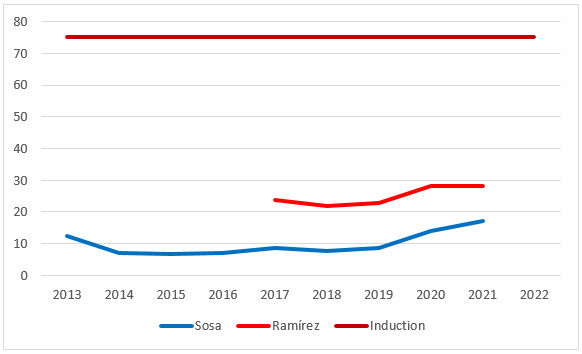

Manny Ramírez and Sammy Sosa

This is what happens when you have significant performance-enhancing drug associations and are not one of the ten greatest players in the history of the game:

Sosa will fall off the ballot with Bonds, Clemens, and, most likely, Schilling after next year. I don’t expect the first three of them to have an easier time of it with the Eras Committees. Ramírez has another five years to go, but he’s not going anywhere with two positive PED tests on his record, which is two more than everyone else on the ballot combined.

Andy Pettitte and Bobby Abreu

Andy Pettitte has gone from 42 to 45 to 55 votes in his three years on the ballot, but that last is still just 13.7 percent. He’s likely trapped in that sub-20-percent limbo for the foreseeable future.

Bobby Abreu survived his first ballot by just three votes. This year, he added 13 more, but is still in the single digits in terms of percentage. Abreu can note that Andruw Jones went from 7.5 percent to 19.4 in his third year and now seems to be on a path toward induction. I don’t think Abreu will have the same fortune, but don’t count him out just yet. Among the bottom five survivors, he might have the strongest candidacy.

The New Guys

Three of this year’s first-year candidates cleared the five percent minimum required to return on next year’s ballot. In order of support, they are former White Sox ace Mark Buehrle (11 percent), Gold Glove centerfielder Torii Hunter (9.5 percent), and former A’s and Braves workhorse Tim Hudson (5.2 percent). Hudson’s 21 votes matched the minimum number required to return. None of those three are Hall of Famers in my mind, but the reason players are given 10 years of eligibility is that minds can be changed. It is happening for Rolen, Helton, Jones, and Wagner, and it could happen for one or more of the players in the bottom five, as well.

Newswire

Cactus League hosts request Spring Training be delayed

On Friday, the leaders of the Cactus League’s eight host cities and the Salt River Pima-Maricopa Indian Community sent a letter (which you can read here) to Commissioner Rob Manfred requesting a delay to the start of Spring Training in Arizona. The signees cited the difficulty of maintaining a safe environment with the players’ mid-February reporting date fast approaching, and COVID-19 cases spiking in the state.

I have two, somewhat contrary, reactions to this. The first is that, I am very sympathetic to any and all efforts to stem the spread of COVID-19 and to protect people from infection. Prior to the start of the 2020 season, I wrote multiple columns and was publicly outspoken about the fact that the season should not have been played. As much as I did ultimately enjoy the 2020 Major League Baseball season, I still feel that it should not have happened. Just because you got home safely, doesn’t mean it was okay to drive drunk, or that you should do it again. The Cactus League hosts are correct in their safety assessment here and correct to ask for a delay.

The second is that this letter, which was made public on Tuesday, doesn’t seem entirely above board. There are three passages that lead me to that conclusion.

First: “the task force has worked to ensure that ballparks are able to meet COVID-19 protocols such as pod seating, social distancing and contactless transactions.”

Those are protocols for fans, not players or staff. If Major League Baseball could play a 60-game season and the vast majority of an expanded postseason without fans in the parks last year, surely it could let the players prepare for this season without having to have fans in the stands for exhibition games at stadiums that have much smaller capacities and much lower ticket prices.

Second: “This position is based on public data from the University of Washington’s Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, which projects a sharp decline in infections in Arizona by mid-March (an estimated 9,712 daily infections on February 15 and 3,072 daily infections on March 15).”

Those dates imply a delay of a full month. (There is no explicit length attached to the requested delay elsewhere in the letter, but The Athletic’s Ken Rosenthal called for a month delay in his column on Monday, and subsequent reporting, linked below, confirms that intent.) However, the exhibition schedule isn’t slated to begin until February 27. If the concern is about fans, not about players and staff (a smaller contingent on which protocols could more easily be enforced), a mere two-week delay would push the first exhibition games to March 13. If pitchers and catchers can still report on time for workouts and throwing sessions in otherwise mostly empty facilities, MLB could trim two weeks off the exhibition schedule and still start the season on time. Last year’s Summer Camp spanned just three weeks from players reporting on July 2 to Opening Day on July 23. This year’s spring training could be of similar length, but with pitchers and catchers reporting earlier to get the former fully up to speed for the season.

Third: “We understand that any decision to delay spring training cannot be made unilaterally by MLB.”

This is the tell. Manfred may be the addressee, but this letter isn’t directed toward him. After all, the leaders state in the second paragraph that they met with MLB representatives and provided an update just the week before. No, this letter is aimed at the Players’ Association, most likely at Manfred’s request, as a result of that meeting from the week before. [This suspicion was mostly confirmed by this report in The Athletic, though the parties involved continue to deny it. That report was published Tuesday afternoon, after I had completed this section of the newsletter.]

You see, the players want to play a full season this year, but the owners don’t want to play any more games without fans in the stands. So, before the players can make them look greedy and heartless for insisting on having fans in the stands, the owners are hoping to make the players look greedy and heartless for wanting to play a full season.

Financial interest is clearly the primary motivation on both sides. The owners want to maximize their profits. The players don’t want to see their salaries reduced (last year they were pro-rated to the shorter schedule), nor do they want to undermine their bargaining power in arbitration and free agency.

Those are not the only motivations, however. The players could lose not just salary but important, irretrievable opportunities. The lifespan of an athletic career is not very long, and the peak of such a career is even shorter. When games aren’t played, prospects lose crucial development time and exposure, young players could miss the small windows they have in which to establish themselves in the majors, star players lose portions of their peaks that will influence both their legacies and their earning power beyond this season, and aging players are robbed of their last days as major-league-quality players.

Meanwhile, the owners may be hiding behind concerns about community spread of the virus, but those concerns are very real and very serious. Tuesday afternoon, we learned of the death of Ron Johnson—who spent 41 years, from 1978 through 2018, as a major or minor league player, coach, or manager, and was also the father of former major-league third baseman Chris Johnson—from complications of COVID-19 at the age of 64.

What all of this amounts to is that, after the contentious offseasons of 2017-18 and 2018-19 (discussed in this space on Monday) and last summer’s failed negotiations over the shortened season, the players and owners (the latter represented by the commissioner) have become completely incapable of recognizing their shared interests (which are, primarily, the overall popularity and financial health of the sport, and the health and safety of both on and off-field employees). If these two sides were capable of reaching an agreement, they’d be working toward one behind closed doors. Instead, reports such as Rosenthal’s, tell us that negotiations are at a standstill. So, instead of progress, we get attempts to manipulate public perception, such as this Cactus League letter, a letter which seems like a bad omen on its face, and may be even worse.

Sticky-stuff suit dismissed

The lawsuit that former Angels employee Brian Harkins had filed against the team and Major League Baseball, related to his providing pitchers with a sticky substance that violated MLB’s rules, was dismissed by Orange County Superior Court Judge Geoffrey T. Glass. That decision came on Monday, after I made mention of the lawsuit in Issue 1 of The Cycle, incorrectly classifying it as a wrongful-termination suit. In fact, it was a defamation suit, with Harkins, who had managed the visiting clubhouse at Angel Stadium, claiming that the publicity surrounding his firing last March had damaged his reputation. Glass’s dismissal asserts that, not only did the Angels not make a public statement about the reasons for Harkins’ firing (the sources cited in connection with those reasons in reports about his firing were all anonymous), but there was no evidence that the Angels’ accusation was untrue.

Indeed, Harkins never argued that it was untrue. Rather, he argued that such substances are widely used throughout the game, thus his reputation was damaged, not by the accusation itself, but by the implication that he was somehow unique in the violation. “All the other kids did it, too,” doesn’t strike me as a strong legal argument, nor does “you besmirched my name by telling the truth about the rules I broke.”

Still, Harkins intends to appeal, and his lawsuit is a reminder that MLB needs to figure out its sticky-stuff problem. Harkins’ argument may not be legally viable, but he has a point. Somehow, Baseball has allowed the use of sticky substances by pitchers to become commonplace, widely accepted, and against the rules, all at the same time. This is not a new issue. I wrote it about for SI.com nearly seven years ago, when the Yankees’ Michael Piñeda was spotted with something that looked a whole lot like pine tar on his pitching hand on a cold April night in the Bronx. It wasn’t new then, either.

The easy solution would seem to be legalizing the stuff, but taking the reins off completely could lead to excessive gooping-up of baseballs. That would not only give the pitchers a better grip—something most hitters are willing to allow in exchange for reducing the chance of a slick ball slipping out of a pitcher’s hand and hurtling toward their head at close to 100 miles per hour—but it could make the ball darker and harder to see, which would give pitchers another advantage and make inside pitches more dangerous for batters. Ray Chapman, the only player ever to die from an injury suffered in a major league game, is said to have never seen the pitch that killed him. Goopy balls (that’s a technical term) could also affect the moment of contact with the bat, its flight thereafter, and the ability of fielders to catch, transfer, and throw the ball. Pitchers’ current need to be surreptitious is, at the very least, keeping the goop in check.

Just two weeks ago, The Athletic’s Brittany Ghiroli and Eno Sarris collaborated on an article about this issue that reminded readers that MLB experimented with a sticky-surfaced ball in Spring Training in 2019. Nippon Professional Baseball and the Korea Baseball Organization have had success with sticky balls (a slightly more legitimate technical term). Ghiroli and Sarris quoted former major leaguer Dan Straily’s praise for the KBO ball: “I didn’t use pine tar all year . . . I didn’t need to.”

MLB’s efforts to develop a viable sticky ball have thus far been unsuccessful, but that solution seems like the one that will ultimately succeed, as it has overseas. The sticky balls don’t need to be rubbed up with mud, so they are not only tackier but also whiter than the current MLB balls. That means they would help both pitchers and hitters, not just the former. Because the stickiness doesn’t require pitchers to apply a foreign substance, all pitchers would have equal opportunity to benefit from the change, and no rule change would be required.

Sarris and Ghiroli argue that having an already-sticky ball wouldn’t prevent some pitchers from continuing to use additional sticky substances. They are right, but that wouldn’t be a step backward, and I believe teams and umpires would be more likely to enforce the existing foreign-substance rules if they knew that the baseline was an already-sticky ball.

The real catch is that, as we’ve already seen in recent seasons, even the smallest changes to the ball can have outsized effects on the way it travels, and thus on home run rate and run scoring throughout the league, and this is no small change. Both getting the texture right for pitchers, hitters, and fielders, and doing so without altering the behavior of the ball (specifically its drag and its coefficient of restitution, a.k.a., bounciness) may be too tall a task. Still, it’s a goal worth pursuing, as it may be the only viable solution.

Transaction Reactions

Phillies re-sign C J.T. Realmuto ($115.5M/5yrs)

In listing Realmuto as the top unsigned free agent on the market on Monday, I wrote, “Something like a five-year, $120 million deal . . . might get it done.” This is very much something like that. Realmuto reportedly wanted to break Joe Mauer’s record for average annual value for a catcher, as much to lift the standards of pay for the position as for any kind of bragging rights. Mauer’s record was $23 million. The AAV of Realmuto’s new contract is $23.1 million. Clearly, those reports were accurate. The contract will take Realmuto, who will turn 30 in March, through his age-34 season. That’s an easy commitment to make to keep the best catcher in baseball, and retaining Realmuto for another five years validates the Phillies’ willingness to part with pitching prospect Sixto Sánchez and catcher Jorge Alfaro to acquire him prior to the 2019 season.

Blue Jays sign SS Marcus Semien ($18M/1yr)

This is a curious one. As the A’s shortstop, Semien finished third in the American League’s Most Valuable Player voting in 2019. However, after an off-year in the abbreviated 2020 season, and with a murderer’s row of shortstop talent due to hit free agency in November (again: Francisco Lindor, Corey Seager, Carlos Correa, Trevor Story, and Javier Báez), he has opted to take a one-year pillow contract with the Blue Jays and move to second base, in deference to both emerging star Bo Bichette and that imposing upcoming class of rival shortstops.

Semien is obviously betting on himself to rebound at the plate, but simultaneously hoping to avoid direct competition with Lindor and company by establishing himself at the keystone. Semien last played on the other side of the bag in 2014, when he made 25 starts at second for the White Sox. Given the successful effort he made to improve his play at shortstop, I have no concern about his ability to make the position switch, which will push Gavan Biggio to third base full time. I’m also confident that he will rebound, at least to some degree, at the plate (bad luck on balls in play was a big factor for Semien in 2020, but 2019 still stands way above the rest of his career in terms of plate production).

The bigger question is if Semien and the Jays can make this one-year contract count. The Jays have been aggressive this offseason, handing out the winter’s richest contract to George Springer despite an already well-staffed outfield, adding Semien to an already talented infield, and making smaller moves to shore up the bullpen with one-year deals for Kirby Yates and Tyler Chatwood, the guarantees of which combine to be less than half what Semien will make this year. Signing Semien means the Jays are likely out on Justin Turner and Andrelton Simmons, but they’re still believed to be interested in Trevor Bauer, who may demand a larger contract than Springer, and is certainly after a higher salary.

Coming off a .533 winning percentage and spot in last year’s expanded playoffs, do the Blue Jays have enough now to make a postesason without a similarly expanded playoff field? Would Bauer put them over the top? Such a run could certainly help inflate Semien’s value heading into next winter. Also, with the infield now full (from third to first: Biggio, Bichette, Semien, and Vladimir Guerrero Jr.), Lourdes Gurriel Jr. is clearly remaining in the outfield. So, will the Jays will try to trade incumbent centerfielder Randal Grichuk?

Keep an eye on the Jays. They’re not done.

Twins sign SS Andrelton Simmons ($10.5M/1yr)

This signing also involves a move across the keystone, though, in this case, it’s not the new guy, Simmons, but the incumbent shortstop, Jorge Polanco, who is making the move. Polanco has played just five games at second base in the majors, but he played it extensively in the minors as recently as 2016. He has his reps there. The transition should go smoothly.

Meanwhile, the incumbent second baseman, Luis Arraez, will return to his 2019 role as a utility man. In 2019, Arraez played eight or more games each at second, third, short, and left field. Given the recent fragility of Simmons, third baseman Josh Donaldson, and the fact that top outfield prospect Alex Kirilloff has played a grand total of one major league game (in last year’s postseason, no less), there should be plenty of playing time for Arraez in the coming season. That makes the Simmons signing both a depth move and an upgrade at shortstop.

From Simmons perspective, however, he’s headed right into next winter’s shortstop crunch. This one year deal makes him the equivalent of next offseason’s Freddy Galvis, the consolation prize for the team that didn’t get one of the big guys (ironic, since Simmons was one of this offseason’s big guys at short stop). It’s surprising that he didn’t demand at least an option on this deal that could have potentially leapfrogged him over next year’s absurd crop of free-agent shortstops.

Cleveland re-signs 2B César Hernández ($5M/1 yr + club option)

Hernández is an underrated player. He is a switch-hitter with a career .352 on-base percentage. In 2020, he won the American League’s Gold Glove at second base and led the league in doubles with 20 in just 58 games. I thought Cleveland might try to use both Andrés Giménez and Amed Rosario, the two shortstops they acquired from the Mets in the Francisco Lindor trade, in the middle infield in 2021. Perhaps they’ll try Rosario in center, instead. That was something the Mets had been contemplating prior to the trade.

Tigers sign C Wilson Ramos ($2M/1yr)

Ramos had a poor season at the plate in 2020, but he was an All-Star as recently as 2018 and has been an above-average bat and a strong defender behind the plate over the course of his career. He’ll turn 34 in August, but for a rebuilding team like the Tigers, he should provide a valuable veteran presence behind the plate and a significant upgrade over what Detroit got from Austin Romine last year.

Orioles sign SS Freddy Galvis ($1M/1yr)

On Monday, I figured the A’s, Phillies, Reds, and Brewers constituted the bulk of the market for the big three free-agent shortstops on the market (Semien, Simmons, and Didi Gregorius), and had Galvis pegged to end up with the team that failed to sign any of them. Tuesday night, three of those players, including Galvis, signed, none of them with one of those four teams. That should give Gregorius a ton of leverage. Then again, the fact that Semien and Simmons both signed one year deals could have set the market lower than Didi would like. Surely he is smart enough to try to leapfrog next year’s shortstop class.

Oh, right, Galvis. Freddy goes to the O’s, who traded José Iglesias to the Angels in early December for minor league righties Garrett Stallings and Jean Pinto, who have combined for 12 professional innings. Iglesias will make $3.5 million this year, so the Orioles save some money and get two lottery ticket arms while making what is largely a parallel move at shortstop. Small potatoes, but still a nice sequence for Baltimore general manager Mike Elias.

Red Sox acquire RHP Adam Ottavino and minor league RHP Frank German from the Yankees for a player to be named later or cash

This is just the fifth trade between these two rivals since George Steinbrenner bought the Yankees in 1973. That speaks to just how unconcerned the Yankees are about the threat the Red Sox pose in the division this year. It may also speak to how the Yankees’ opinion of Ottavino has dropped since they signed him to a three-year, $27 million deal two years ago.

Ottavino is, after all, a 35-year-old with a problematic walk rate (5.2 walks per nine innings over the last four seasons) who saw his ERA spike by four full runs in 2020. That last was over a minuscule 18 1/3-inning sample, though. If you look past his ERA, Ottavino’s underlying performance in 2020 was arguably better than the year before, as evidenced by his deserved run average dropping from 3.63 to 3.35. That’s a valuable performance, but not at the level of the actual 2.19 ERA he posted over 144 innings between the 2018 and ’19 seasons. I wouldn’t expect that kind of dominance from him again. Still, in Boston’s thin bullpen, Ottavino could challenge Matt Barnes for closing opportunities, which means the Yankees might have just given the Red Sox a closer for next to nothing.

Not just a closer, but a closer, a kid, and cash ($850,000, per Buster Olney). Frank German—not to be confused with Domingo Germán, nor former Tiger Franklyn Germán (though Frank’s full name is Franklin)—was a fourth-round pick out of the University of North Florida in 2018. A slender righty, he spent most of 2019 in the rotation with High-A Tampa with unexceptional results. He’s now 23 and not much of a prospect, just a warm body. German represents Queens, while Ottavino was raised out in Brooklyn, which makes this trade between New York and Boston feel even stranger, but Ottavino went to college at Northeastern, so he should feel somewhat at home in either city.

From the Yankees’ perspective, the purpose of this trade is to free up $8.15 million of salary ca . . . , er, “competitive-balance tax” space. If the Yankees follow up this trade by signing Masahiro Tanaka and pushing Jameson Taillon into the bullpen, we might have proof that Brian Cashman reads The Cycle. More likely, according to the rumor mill, is another one-year deal for the now-37-year old Brett Gardner. Gardner’s last deal guaranteed him $12.5 million, but that included a $2 million signing bonus and the $2.5 million buyout of the $10 million club option that the Yankees declined in November, leaving just $8 million as salary. The Yankees are likely hoping that $8.15 million is enough to keep the team’s longest-tenured player in pinstripes.

Getting back to the history of Yankees-Red Sox trades, if we include the selling of players from one team to the other (which, after all, is how Babe Ruth got from Boston to New York), Yanks-Sox trades didn’t really become a rarity until Steinbrenner entered the picture in 1973. Between 1967 and 1972, the two teams made four swaps, including the Yankees sending an aging Elston Howard to Boston in August 1967 to enjoy one last pennant run, and New York fleecing the Sox in the Danny Cater-for-Sparky Lyle swap just before the start of the 1972 season.

With the Lyle trade included for context, here are the last six trades between the two teams, along with the remaining career wins above replacement for the players involved (that is, from the date of the trade forward), and the difference between the two teams in the standings at the end of the season in question:

*final standings from the 60-game 2020 season

As you can see in the Final Standings column, over the last three decades, these trades have only happened when the Red Sox have not posed a threat to the Yankees in the division. Even then, the Bankhead and Drew/Johnson deals amounted to almost nothing. The former came after the start of the 1994 strike, and Bankhead posted a 6.00 ERA in 39 innings for the Yankees in 1995, his final major-league season. Drew was awful for the Yankees down the stretch in 2014, posted a 77 OPS+ in 2015, then left as a free agent. Meanwhile, Johnson played just 10 games for Boston before the Sox traded him again, on August 30, this time to Baltimore.

The other two swaps are more interesting. The 1986 deal was a straight-up challenge trade between what would prove to be the top two teams in the American League East that year. The perception at the time was that the Red Sox won the deal. Baylor hit 31 homers and was hit by a major-league leading, and career-high, 35 pitches that year. He then hit .346/.469/.577 against the Angels in the American League Championship series as Boston won its first pennant in 11 years. Over the next two seasons, his last in the majors, Baylor returned to the World Series with the Twins and A’s. The Yankees, meanwhile, needing pitching more than another bat, finished 5 1/2 games behind the Red Sox, and would have to wait another decade to return to the playoffs.

On the merits of the trade alone, however, the Yankees may have actually done better. Baylor was good in 1986, posting a 112 OPS+, but Easler was a year-and-a-half younger and hit .302/.362/.449 that season, good for a 121 OPS+. Both players were then traded, Baylor to the Twins for a career minor leaguer, Easler to the Phillies in a four-player deal that brought right-hander Charles Hudson to the Bronx. Hudson posted a 123 ERA+ in 154 2/3 innings in 1987, briefly looking like the pitcher New York needed, but by then the Yankees were already starting to decline.

The post-Lyle Yankee-Red Sox swap with the greatest legacy, however, is the one from 1997. As a good-hitting catcher, Mike Stanley was a key part of the Yankees’ return to respectability under Buck Showalter from 1992 to 1995. He signed with Boston as a free agent prior to the 1996 season, when new manager Joe Torre convinced the team to go with a glove-first backstop in Joe Girardi. In 1997, New York reacquired Stanley on the downslope of his career for a successful stretch run, with Stanley posting a 127 OPS+ as a designated hitter and first baseman and going 3-for-4 in the postseason. Stanley then left as a free agent again, this time for Toronto.

Though they would go on to combine for 16 wins above replacement, neither Armas nor Mecir ever played a game for Boston. Still, the Sox were the easy winners of that trade. Mecir was lost to the Devil Rays in that fall’s expansion draft, but Armas was one of the two pitching prospects, along with future Yankee Carl Pavano, that the Red Sox sent to the Expos that December for 26-year-old incumbent National League Cy Young-award winner Pedro Martínez. That sequence was masterful work on the part of Boston general manager Dan Duquette, who had also acquired Martínez for the Expos as their GM in 1993.

Happy Birthday, Luna!

My family lost our beloved dog, Maisie, to a spinal tumor around Thanksgiving 2019. We grieved through the holidays, then began looking for a new puppy. It was a long, hard search, but we finally found one that fit in March and agreed to adopt her right before the pandemic shut everything down. She, her ten litter mates, and their mother, Maize, were fostered and carefully placed by the Australian Cattle Dog Rescue Association (the dogs are part cattle dog, plus parts of many other things). We brought Luna home on April 3 of last year, and she has been crucial to our collective mental and physical health for the last 10 months. On Tuesday, Luna celebrated her first birthday, so my wife made her a dog-food “cake” decorated with treats and string cheese. We might need to get out more, but, fortunately, Luna gives us good reason to. I just thought I’d share.

Reader Survey

Thank you to everyone who responded to the reader survey in Monday’s debut issue. I’m including it again here for those who haven’t gotten around to it or didn’t see it. Again, in order to serve you better, I would like to know a little more about you. This is optional, of course, but, if you don’t mind, please reply to this issue with:

your favorite team (or teams, or if you are a general-interest baseball fan)

your general location (as many of the following as you feel comfortable sharing: city, state, province, country for those outside the U.S. and Canada)

your birth year (because it doesn’t change, unlike your age)

The idea here is to know whom I’m writing for, what teams you want to read about, and when and where you’ll receive the newsletter. I can’t promise I’ll write more about the Marlins if you tell me you’re a Marlins fan, but if there’s a large Marlins contingent among the readership, I will likely lower my threshold for including Marlins items and dive deeper into the ones I include.

Closing Credits

“Nothing Was Delivered” is a Bob Dylan composition recorded by Dylan with the Band in the basement of the house they called Big Pink in Saugerties, New York in late 1967 as part of what would come to be known as the basement sessions. The first official release of this version came on The Basement Tapes in 1975, though the Byrds, as was their wont with Dylan songs, covered it in 1968 on their alt-country classic Sweeheart of the Rodeo. I prefer the Dylan version, which has a kind of Fats Domino roll to it thanks to Rick Danko’s bass line and Richard Manuel’s piano. The lyrics are easier to understand on the Byrds version, but it’s a dark, bitter song, and this version communicates that mood better. The second verse is perhaps the most on-point for last night’s Hall of Fame results, and a few of the candidates:

No, nothing was delivered

I can't say I sympathize

With what your fate is going to be

Yes, for telling all those lies

Now you must provide some answers

For what you sell was not received

And the sooner you come up with them

Then the sooner you can leave

The Cycle will return on Friday. In the meantime, please help spread the word!