The Cycle, Issue 1: Setting the Table

Taking stock of the Hot Stove, remembering Hank Aaron, and an introduction to The Cycle

Welcome to The Cycle!

Today’s debut issue joins the offseason already in progress and takes stock of what has and hasn’t happened thus far this winter. Specifically, I look at how this winter’s free-agent market has developed, rank the top free agents still unsigned, and check in on the latest from the rumor mill with regard to their markets.

Also:

Transaction Reactions

Hank Aaron (1934-2021)

Author’s Note/Introduction

Reader Survey

Closing Credits

A couple quick notes:

Before we get started, word of mouth is going to be very important to the growth and survival of The Cycle. Please spread the word, on social media and in person, and let people know what it was you liked about this issue of The Cycle and why (I hope) you can’t wait for the next one!

Also, this issue covers the events in Major League Baseball since Friday morning, which is when the previous issue would have been delivered, had there been one. Despite that, this issue went a little long. If you have any trouble seeing all of it on your email, you can read the entire issue at cyclenewsletter.substack.com. And if you are already reading it there because you haven’t subscribed yet, you can fix that by clicking here:

Setting the Table: Taking stock of the Hot Stove

This has been one of the most unusual offseasons in major-league history because of the still-raging COVID-19 pandemic. Typically, I would have little sympathy for teams that cry poor, but the league as a whole inarguably took a financial hit in 2020 given the abbreviated 60-game season and the total lack of ticket and concessions sales. In addition, there is lingering uncertainty about the coming season, not just about the league’s ability to play it (though, thus far, Major League Baseball expects to start on time and play a full season), but about the rules they’ll be playing under. Specifically, we have still not had official word from the commissioner’s office as to whether or not there will be a designated hitter in the National League this season or what the playoff format will be following last year’s expanded postseason. Given that, it’s hardly surprising that this winter’s Hot Stove has been slow to boil.

Still, it is troubling, particularly given that we saw a similarly slow free-agent market, pre-pandemic, in both the 2017-18 and 2018-19 offseasons. The reasons for this winter’s glacial pace don’t change the fact that the Collective Bargaining Agreement between the owners and the Players Association will expire in December with the league having had just one “normal” free agency class in the preceding four years.

Part I: The Big Picture

Before I get into the specifics of who has and hasn’t signed this winter, let’s take a look at those last four offseasons, using today’s date, January 25, as a dividing line.

In the 2017-18 offseason, the market for free agents seemed to go suddenly cold. In a typical year prior to the 2017 season, most of the high-profile free-agent signings would happen in November and December, with a few stragglers carrying over into the new year, but all of the highest-profile players finding teams well in advance of Spring Training. In 2018, however, pitchers and catchers reported with several of that winter’s top free agents—Eric Hosmer, J.D. Martinez, Jake Arrieta, Lance Lynn—still unsigned. Of the 40 free agents to sign contracts with a total guarantee of $10 million or more that offseason, 30 percent of them signed after January 25, adding the likes of Yu Darvish, Lorenzo Cain, and Todd Frazier to that group. What’s more, six of the eight richest free-agent contracts handed out that winter were signed after January 25.

The following winter was only a slight improvement, with 22 percent of all free agents who signed eight-plus-figure contracts doing so after January 25. The offseason’s top two targets, Bryce Harper and Manny Machado, didn’t sign until late February, and pitchers Dallas Keuchel and Craig Kimbrel, whose free agencies were burdened by draft-pick compensation, didn’t sign until after the first round of the draft in early June.

Those two offseasons prompted players, agents, and members of the media to have a public conversation about the likelihood of collusion on the part of the owners. Perhaps in response, things seemed to return to normal last winter. Nicholas Castallanos was the only free agent to sign an eight-figure deal after January 25, and he did so on January 27. Meanwhile, Gerrit Cole signed a record pitching contract with the Yankees ($324 million over nine years), and Anthony Rendon and Stephen Strasburg inked identical seven-year deals with a similar $35 million average annual value.

This year, however, we’re back to the Big Wait. As we wake up today on January 25, the list of free agents still unsigned this winter includes J.T. Realmuto, Trevor Bauer, Marcell Ozuna, Nelson Cruz, Marcus Semien, Justin Turner, Didi Gregorius, Masahiro Tanaka, and several others who could reasonably expect to sign for eight-figures or more.

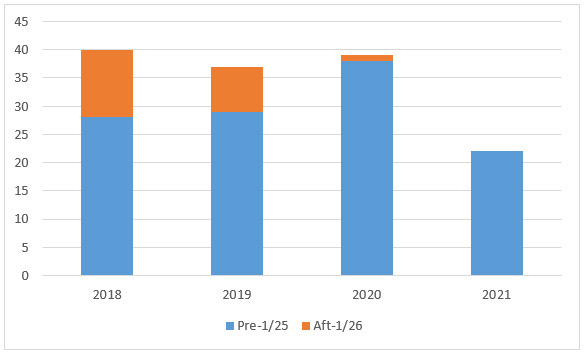

Here’s a look at the breakdown between pre- and post-January 25 free-agent contracts worth $10 million or more over the last four offseasons:

Every free-agent class is different, and this, in my opinion, was a particularly weak one to begin with. Still, this offseason is running behind even 2018 and ’19 by this metric. Because today is January 25, that blue bar over 2021 isn’t going to get any taller. Every eight-figure free-agent contract signed from here on out would be in orange above it.

That graph also illustrates that, while last winter’s market moved faster, it wasn’t necessarily any larger in terms of the quantity of big free-agent contracts signed. In terms of the total dollars committed via eight- or nine-figure free-agent contracts, 2017-18 totaled $1.37 billion, 2018-19 totaled $1.65 billion, and 2019-20 totaled 1.97 billion. Take Gerrit Cole’s record-setting deal out of last year’s total, and there was less money spent on the next 38 largest free-agent contracts last year (even with Rendon and Strasburg included), than on the top 37 the previous year.

This year—even if we include DJ LeMahieu, whose six-year, $90 million contract still hasn’t been officially announced by the Yankees (though it is included in the 2021 total in the graph above)—there has been just $622.3 million committed on free-agent contracts of eight figures or more, and there aren’t any mega-contracts still to come, as there were in 2019 with Harper and Machado signing late.

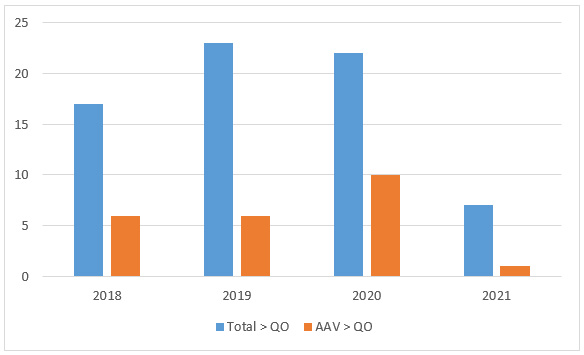

Before I break down this year’s market, I have one more graph I want to share. This one shows the number of free-agent contracts from each of the last four offseasons that surpassed the qualifying offer in total value and in average annual value. The qualifying offer is a good baseline to use because its value is determined by taking the mean salary of the game’s 125 highest-paid players. It was $17.9 million in 2018, remained there in 2019, fell to $17.8 million in 2020—evidence of just how broken free-agency had been the previous two years—and leapt to $18.9 million this year (thanks to Cole, Rendon, and Strasburg, plus scheduled salary increases in older contracts).

Here’s what the last four offseasons have looked like relative to the qualifying offer:

Even with LeMahieu included, there has been just one free-agent contract signed thus far this offseason that has surpassed the qualifying offer in average annual value. That is, just one contract that has exceeded the average salary of the game’s 125 highest-paid players. That was George Springer’s six-year, $150 million deal with the Blue Jays (average annual value: $25 million). The next highest AAV is that of the two pitchers who accepted their teams’ qualifying offers, Marcus Stroman and Kevin Gausman with the Mets and Giants, respectively. Fourth place isn’t LeMahieu. The Yankees spread his $90 million over six years to avoid triggering the competitive balance tax, which has worked as a de facto salary cap over the last four offseasons and will surely be a primary target of the union in the fall. No, after the qualifying offer, the next highest average annual value of the winter is the $18 million per year over three years the White Sox are paying Liam Hendriks to be their new closer. We’re far too late in the offseason for a 32-year-old reliever to hold such a distinction.

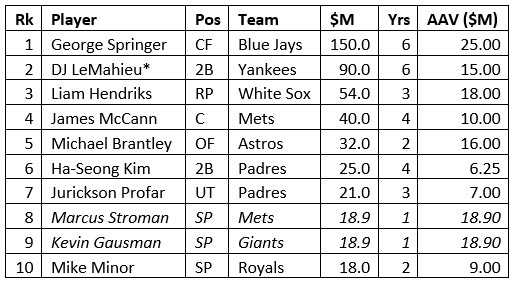

With all of that out of the way, here are the ten largest free-agent contracts, in total value, handed out thus far this offseason:

*LeMahieu gets an asterisk because his deal is still technically unofficial. Stroman and Gausman are in italics because they accepted the qualifying offer.

Part II: The Unsigned Free Agents

So, who is still out there? This is my personal top 10, along with the latest rumors about their potential landing spots:

1. J.T. Realmuto, C

The Player: The consensus best catcher in baseball is an all-around athlete who has hit .282/.336/.466 (115 OPS+) over the last five years and is an asset both behind the plate and on the bases. He won’t turn 30 until March, and his free agency comes amid a league-wide low point for catching production. He would improve any team in baseball, most of them dramatically.

The Market: A return to the Phillies still appears to be the most likely outcome, in part because Realmuto declined their qualifying offer, thus attaching draft-pick compensation to his free-agent price. Realmuto is said to be seeking a record average annual value for a catcher (the current mark is Joe Mauer’s $23 million), which seems like an easy price to meet in the near term. For a catcher about to turn 30, it’s the contract’s length that’s likely the issue. Something like a five-year, $120 million deal (AAV: $24 million) might get it done.

Meanwhile, the Braves are reportedly showing interest, though that could just be to drive up their division rivals’ price, as are “teams on the west coast,” per Fansided’s Robert Murray. Flipping through those teams in my head, that most likely means the Angels. The Dodgers have Will Smith. The A’s have Sean Murphy. The Mariners and Giants are too far from contention, and the latter has Buster Posey set to return. The Padres have been aggressive, but they seem to have a good thing in Austin Nola. The Angels just signed Kurt Suzuki, but he’s 37 and cost $1.5 million. Still, look for Realmuto to head back to Philly.

2. Marcus Semien, SS

The Player: Semien is a talented player who steadily improved his game after being traded from the White Sox to the A’s in December 2014’s Jeff Samardzija swap. In 2019, he burst into full flower, with 33 home runs, a 139 OPS+, and a third-place finish in the American League’s Most Valuable Player voting for what Baseball-Reference calculates as a nine-win season. In 2020, however, he wilted on both sides of the ball.

So who is he? Is he one of the best shortstops, and thus players, in baseball? Or is he a talented but erratic player capable of great things but more often than not struggling to deliver them? This is the lingering problem of the 2020 season. How do we evaluate that small sample, played without regular access to the video that so many players use to make in-game adjustments, particularly when that 2020 performance differs so much from what came before it? Me, I trust the growth Semien showed over multiple full seasons prior to 2020 more than those small-sample struggles and rank him just ahead of his shortstop brethren, who are both a year older than he is.

3. Didi Gregorius, SS

The Player: Gregorius lost the first half of the 2019 season to Tommy John surgery, but appeared to return fully to form in 2020, hitting .284/.339/.488 (119 OPS+) with 10 homers in the 60 game season. He’ll turn 31 around the time pitchers and catchers report (he’s actually just seven months older than Semien) and adds an above-average glove, an elite clubhouse presence, and a raft of postseason experience to that capable bat. In the two seasons before his Tommy John surgery, he averaged 4.6 bWAR, and I think he can continue to be that player for several more seasons.

4. Andrelton Simmons, SS

The Player: One of the best fielding shortstops in major-league history, Simmons struggled to stay healthy over the last two years and will turn 32 before the coming season ends. Still, he was a league-average bat in his five years with the Angels, rarely strikes out, offers speed on the bases, and, if he can stay healthy, his work in the field will pay for itself.

The Market: For all three of the shortstops above, the big question is: who needs a shortstop? Certainly, Semien and Gregorius’s old teams, the A’s and Phillies, do, but the Angels moved quickly to put José Iglesias in Simmons’ spot, and the Orioles, Iglesias’s old team, aren’t buyers right now. Cleveland just traded Francisco Lindor, and that, alone, indicates that they have no interest in either contending or spending money on a shortstop for 2020. Besides, they got Andrés Giménez and Amed Rosario in the deal.

Among possible contenders, the Brewers, who may want to upgrade on Orlando Arica, and the Reds, who have a hole at the position, would be the other most likely landing spots. With the A’s and Phillies, that’s enough teams to play a game of musical chairs with these three shortstops, with the loser getting Freddy Galvis. Still, there’s a sense that this is like three guys trying to fit through a door at once. If there was a more obvious hierarchy among them, or just one of them was on the market, they’d probably have signed sooner.

Also hanging over the market for these three is the promise of next winter’s shortstop bumper crop, with Lindor, Corey Seager, Javier Báez, Carlos Correa, and Trevor Story all due to reach free agency in November. I expect that more than one of that quintet will sign an extension with their current club before hitting the market. Still, their potential availability could be preventing this year’s trio from getting long-term offers, contributing to the freeze on their market.

5. Marcell Ozuna, LF

The Player: Ozuna had monster seasons at the plate in two of the last four years, but he was just slightly above average in the two in between, and he’s a sub-par defensive outfielder. The question here is if the 30-year-old righty can keep raking like he did last year, when he led the National League in homers (18), total bases (145), and RBI (56), posting a career-high 175 OPS+, albeit in just 267 plate appearances. Well, maybe not at that level, but I’d be willing to bet on his bat, which has also proven itself in the postseason, with a .534 slugging percentage and five homers across 21 postseason games.

The Market: Ozuna is one player whose market has surely been slowed by Major League Baseball’s refusal to announce whether or not there will be a designated hitter in the National League this year. (I don’t have time for the rant here, but it’s absurd to ask teams to endure an entire offseason, or, really, any part of one without knowing if they’ll need eight or nine hitters in their lineup in the coming season.) Nonetheless, Z Deportes’s Héctor Gómez lists the Dodgers, Mets, and Brewers, all NL teams, along with the AL’s Yankees, Red Sox, and Twins as teams having interest in Ozuna. For his part, Ozuna, after settling for a one-year deal with the Braves last winter, wants at least four-years this time. I see no reason he shouldn’t get it.

6. Justin Turner, 3B

The Player: Turner is 36, a lock for one disabled list stay a season, and his fielding is in decline, but darn if he doesn’t still rake. Turner hit .302/.382/.503 (139 OPS+) in seven years with the Dodgers, and largely replicated that line in both 2019 and 2020, as well as over 314 career postseason plate appearances. His poor choices after getting a positive COVID-19 test in the middle of Game 7 of last year’s World Series aside, he is a great teammate, a valuable veteran presence, and gives back to the community. The only real knock against him is his age. His career could go belly-up at any moment, but if you cover up his birthdate, you wouldn’t expect it to be soon.

The Market: According to the Los Angeles Times’ Jorge Castillo, the Dodgers want to bring Turner back. However, Turner wants a four-year deal, which, given his age and fragility, is, frankly, absurd. The Dodgers won’t go past two years, per Castillo, nor should they, and Turner should take it.

7. Trevor Bauer, RHP

The Player: Is Bauer down here because he’s a budding Curt Schilling? In part. Bauer, a red-pilled, gamergate-type, is going to do or say something problematic, abusive, or possibly even illegal again sooner or later, and it’s going to cause a giant headache for whichever team signs him. His history of such behavior is already extensive enough that signing him would be an affront to a significant portion of any team’s fanbase. I don’t dispute his right to earn a living plying his talents, but I do think teams should think twice, then think again if they really want to spend the length of his contract apologizing for and attempting to spin his behavior; if they really want to get that on them.

With regard to the baseball stuff, Bauer is looking for a record-setting salary, and will also cost a team draft-pick compensation, but he has had just two elite seasons in a nine-year career, they were not consecutive, and one of them spanned just 73 innings. Still, one must contend with the defending National League Cy Young award winner. Bauer has posted a 144 ERA+ with 11.2 strikeouts per nine innings over the last three years, but the middle year of that span saw his walk and homer rates spike and his ERA balloon to 4.48. His small-sample award-winning campaign last year was largely the result of a huge spike in spin rate across all his pitches, something Bauer has made a point of proving often stems from the use of foreign substances. Those substances, incidentally, are central to a lawsuit filed against MLB and the Los Angeles Angels last August by former Angels employee Brian Harkins, who claims he was wrongfully fired for providing such a substance to pitchers on the Angels and other teams.

So you have an inconsistent pitcher who likely cheated* his way to small-sample success last year and is sure to embarrass your organization and possibly bring down other careers with his own. I’ve probably ranked him too high.

*To be fair, the use of sticky substances is an open secret within the game and a very common practice. I’m sure I’ll write more about it in future issues in reaction to developments in the Harkins case.

The Market: According to the Ken Rosenthal story that ignited a twitter grease fire over the weekend (due to Rosenthal initially downplaying Bauer’s offenses, a reminder of the kind of kindling Bauer provides), the Mets, Dodgers, Blue Jays, and Angels are all interested in this mess, but the Twins are not. Of that lot, the Angels seem the most desperate. I just hope Bauer doesn’t red-pill Mike Trout.

8. Nelson Cruz, DH

The Player: Cruz is four years older than Turner and exclusively a designated hitter at this point in his career, but his bat seems only to improve as he ages. Over the last six seasons, he has hit .289/.369/.563 (152 OPS+) while averaging 37 home runs per year. Meanwhile, where’s what his OPS+ has done over consecutive two-year spans since he turned 30:

That’s goofy. Cruz drew a performance-enhancing drug suspension in late 2013 in connection with the Biogenesis scandal, but that was his age-32 season, and he has passed all of his tests since. Like Turner, the end is near for Cruz, who will turn 41 in July, but you wouldn’t know it from his performance on the field.

The Market: Cruz’s market is also complicated by the lack of a decision on the universal DH. Thus far, it seems, he has been playing chicken with the Twins, asking for a two-year deal while the Twins increase their offer on a one-year pact. Minnesota’s interest in Ozuna may just be to leverage Cruz, but they could do worse than to get a player who is a decade younger and won’t kill you in left field. Then again, any team with an open DH spot could do much worse than a one-year deal with Nelson Cruz.

9. Masahiro Tanaka, RHP

The Player: At 32, Tanaka is now more reliable veteran than potential ace. He has assembled a 114 career ERA+ since coming to the United States in 2014 and, despite an early Tommy John scare, averaged 29 starts and 174 innings in the five years between his rookie season and last year’s abbreviated one. What’s more, prior to stumbling last October, he had a 1.76 ERA in eight career postseason starts. Tanaka isn’t going to make a good team great, but he’s a solid piece to have in the rotation and has a habit of coming up big in big spots and a knack for improvising and figuring out new ways to get hitters out.

The Market: SNY’s Andy Martino reports that all Tanaka wants is a one-year, $15 contract. That would still be too expensive for the Yankees if they insist on avoiding the competitive-balance tax. That is, of course, absurd, given the Yankees’ spending power and potential to go deep into the postseason with a proven big-game pitcher like Tanaka in the rotation. You’d be hard pressed to find too many teams that wouldn’t be improved by signing Tanaka to that deal; that list is probably the Dodgers and maybe the Padres, who actually had interest in Tanaka. Still, with MLB pinching pennies, Tanaka might opt to return to Japan for a more lucrative contract, which is a damning condemnation of the state of free agency on this side of the Pacific.

10. Jackie Bradley Jr., CF

The Player: Like Simmons, Bradley makes this list on the strength of his play in the field. Add a roughly league-average bat and speed on the bases to elite centerfield defense, and you have a very valuable player. Bradley’s left-handedness makes him a good candidate for a platoon partner. Fortunately, righty-swinging centerfielders Kevin Pillar and Jake Marisnick are also still unsigned. Bonus: all the “Jackie Rogers Jr.’s $100,000 Jackpot Wad” memes you can handle! (I’d link that classic Saturday Night Live sketch from the 1984-85 season, but it has more black- and brownface than the Virginia state government).

The Market: The Giants have some interest, per the San Francisco Chronicle’s Susan Slusser, who has crossed the Bay after more than 20 years covering the A’s. MLB Network’s Jon Heyman adds the Mets, Phillies, Astros, and Rockies, and confirms that the Red Sox haven’t fully turned the page just yet (likely due in part to their flirtations with trading Andrew Benintendi).

Transaction Reactions

Padres re-sign UT Jurickson Profar ($21M/3yrs)

Once the top prospect in all of baseball, Profar seems unlikely to ever blossom into a star now that he’s heading into his age-28 season, but he’s still one hell of a Swiss Army knife (or, in the case of the Curaçaoan Profar, Dutch Army knife). A switch-hitter with power and speed who can play anywhere in the infield or outfield and has been a league-average bat over the last three seasons (.243/.323/.434, 101 OPS+), Profar is an extremely valuable bench player for a stacked Padres team that is likely to challenge the defending champion Dodgers for the division and the pennant in the coming season.

Profar’s contract includes opt-outs after each of the next two seasons, so if he does get a chance to be more than a valuable utility man, he’ll have a chance to cash in before turning 30.

Red Sox sign 2B/UT Enrique Hernández ($14M/2yrs) and RHP Garrett Richards ($10M/1yr + $10M club option)

Speaking of valuable utility men, Kiké Hernández was exactly that for the Dodgers as they won six straight division titles in his six years with the team. Hernandez hit .240/.312/.425 (97 OPS+) for L.A. over that span, with 20-homer power and double-digit appearances at every infield and outfield position. Hernández put up similar numbers in the postseason, with eight home runs in 142 plate appearances, including three home runs against the Cubs in the game that snapped the Dodgers’ 29-year pennant drought in 2017, and a game-tying solo shot to lead off the sixth inning of Game 7 of last year’s National League Championship Game against the Braves. Hernández is also one of the biggest goofballs in today’s game, an easy guy to root for, and a constant source of entertainment inside or outside of the foul lines.

Unfortunately for the Red Sox, rumor has it that Hernández fled the Dodgers this winter because he wanted a full-time job at a single positon. That undermines his value, but, as the Sox’s roster is currently structured, there is opportunity for Kiké to win a full time job at one of his two primary positions: second base or, if Boston doesn’t bring back Bradley, centerfield.

A once-promising Angels starter, Garrett Richards had his career derailed by elbow problems after his age-27 season. Those problems climaxed in Tommy John surgery in July 2018. Mix in last year’s abbreviated season, and he hasn’t thrown as many as 80 innings in a single campaign since 2015. Still, he stayed healthy throughout last year’s abbreviated season and pitched well for the Padres both before and after they bounced him to the bullpen in mid-September. Richards throws in the mid-to-upper 90s with a sinker, slider, and curve, but his fly-ball rates have been heading in the wrong direction, and a move from Petco Park to Fenway for his age-33 season isn’t likely to work in his favor. Still, for a Red Sox team so desperate for starting pitching that they re-signed Martín Pérez, who has a 6.33 deserved run average over the last two years, Richards seems worth the $10 million gamble.

Most importantly, given the Red Sox’s dim outlook for the coming season, Hernández and Richards were sporting glorious moustaches when the 2020 season began. Though Hernández ultimately shaved his off, his cookie duster made him look like Older-era George Michael at times, while Richards’s would have been at home on one of the Three Musketeers. Here’s hoping Kiké grows his back, and he and Richards help Boston return to the gloriously mustachioed mid-80s days of Dwight Evans, Wade Boggs, Bill Buckner, Jim Rice, Tony Armas, Don Baylor, Dave Henderson, Ed Romero, Mike Greenwell, Kevin Romine, and Al Nipper, just to name the most prominent stashes on the 1986 AL Champions, alone.

Nationals sign RHP Brad Hand ($10.5M/1yr) and Ryan Zimmerman ($1M/1yr)

The primary purpose of the Zimmerman contract is to prevent the 36-year-old from ending his career with the decision to opt out of last season. Mr. National started every game of the 2019 World Series at first base and largely replicated his 2019 regular-season line by hitting .255/.317/.418 during Washington’s championship run. The Nats have 28-year-old switch-hitter Josh Bell at his position now, having acquired him from the Pirates earlier in the offseason, but the righty-swinging Zimmerman still has some value as a bench bat and clubhouse presence, and there are bonuses in his contract that could boost its value.

A report by Ken Rosenthal last week had Hand and the Mets on the verge of a two-year contract, but that proved to be erroneous (it was a rough week for Ken, who is a genuinely good guy and tremendous reporter). Instead, Hand is headed to Washington on a one-year deal worth half a million dollars more than the club option Cleveland declined on him in December. That’s a nice upgrade for Hand, and for the Nationals, who will slot him right into the closer’s job.

Over the last five years, Hand has pitched to a 157 ERA+, struck out 12.2 batters per nine innings, and posted a 4.09 strikeout-to-walk ratio in 320 innings, an average of 72 frames per 162 team games. Baseball Prospectus’s deserved run average—which calculates how many runs a pitcher deserved to give up per nine innings after correcting for . . . well, everything you could possibly think to correct for, down to the weather—isn’t buying what Hand is selling, tagging him with a 4.24 DRA in 2019 and a 4.40 mark in 2020. On top of that, Hand has experienced significant velocity drops the last two seasons, shedding roughly one mile per hour each year to go from an average fastball of 93.8 in 2018 to 91.4 last year, per Statcast. Fortunately, for Hand and the Nationals, his primary pitch is his slider, which he throws more than 50 percent of the time, and it’s hard to argue with his actual results. In 2020, Hand didn’t allow a single home run in 22 innings and posted the best walk rate of his career by issuing just four free passes. Still, you wonder if Cleveland was just being characteristically cheap in declining Hand’s option, or if they knew something the Nationals don’t.

Marlins sign RHP Anthony Bass ($5M/2yrs + club option)

This well-traveled 33-year-old is joining his seventh major league team, and sixth team in the last six years, one of which was the Nippon Ham Fighters. He features a mid-90s sinker/slider combination that he compliments with a splitter. With the Blue Jays last year, he threw the sinker more than half the time, inducing ground balls at a career-high rate. With the Jays and Mariners over the last two seasons, he posted a 3.54 ERA across 73 2/3 relief innings with a similar deserved run average. He’ll be a high-leverage arm in the Marlins’ bullpen and will likely battle Yimi García for the closer’s role in camp.

Cubs sign C Austin Romine ($1.5M/1yr)

In his final two years with the Yankees, Romine hit .262/.302/.428 with 18 home runs in 505 plate appearances. That’s starting-quality production from a catcher in today’s game (the average catcher in 2019 hit .238/.309/.408), but he struggled as a full-timer with the Tigers last year and will return to backup work this year, replacing Victor Caratini behind Willson Contreras.

Yankees acquire RHP Jameson Taillon from Pirates for RHP Miguel Yajure and minor leaguers IF Maikol Escotto, OF Canaan Smith, and RHP Roansy Contreras

The Yankees are taking a gamble here. Taillon has a strong pedigree. He was the second overall pick in the 2010 draft, a highly-regarded prospect prior to his first Tommy John surgery in April 2014, and a quality major league starter across parts of four seasons for Pittsburgh after his recovery (112 career ERA+, including a 122 ERA+ in 191 innings in 2018 after beating testicular cancer the year before). In those seasons, he threw in the mid- to upper-90s with a wicked curve and a changeup, and added a 90 mph slider in 2018. Then the elbow went, again. Taillon had his second Tommy John surgery in August 2019 and hasn’t pitched since.

The Yankees seem to expect Taillon to slot right into their 2021 rotation. The good news is that 18 months will have elapsed between his last surgery and the start of Spring Training in mid-February, so his elbow should be as fully healed as it is going to get. The bad news is that history of pitchers who have had multiple Tommy John surgeries provides little precedent for a successful return to front-end starting.

In an SI.com piece about the A’s rushing the ill-fated Jarrod Parker back from his second TJ surgery in 2015, I included this note:

[T]here is little evidence that an elbow that has been subject to multiple Tommy John surgeries can hold up under the rigors of starting pitching. The pitcher with by far the greatest success as a starter following a second TJ is the Yankees’ Chris Capuano, who has made 105 major league starts since having his second ligament replacement in May 2008. Next on the list is Taiwanese lefty Hong-Chih Kuo, who made 14 spot starts for the Dodgers amid a brief major league career as a lefty reliever, all of which took place after his second Tommy John surgery in '03.

Kuo spent four seasons in Taiwan’s Chinese Professional Baseball League after his final major league season, pitching exclusively in relief. Capuano, meanwhile, maxed out at 109 post-second-TJ starts. Among the other two-timers mentioned in that article who were still in the process of working their way back, the leader in subsequent starts was Kris Medlen with 15 spread over four years, the last seven resulting in an 8.89 ERA. Daniel Hudson was also among that group, and he has managed to stay healthy over seven major-league seasons since (he actually returned in late 2014), but he has worked almost exclusively in relief, making just three starts over that span.

Still, there are a few other pitchers to watch as potentially encouraging signs for Taillon and the Yankees. The Red Sox’s Nathan Eovaldi has made 42 starts since his second Tommy John surgery in August 2016 ended his brief stint with the Yankees, and he was still hitting triple digits on the radar gun last year. Young Brewers righty Drew Rasmussen made 23 starts in the minors in 2019 after his second Tommy John surgery and reached the majors for the first time last year. Most significantly, former Rockies and Cubs Righty Tyler Chatwood has made 82 starts since his second Tommy John surgery in July 2014, which puts him just 27 shy of Capuano’s record for a two-time Tommy John recipient. A free agent this winter, Chatwood signed a $3 million contract with the Blue Jays last week, though it appears they intend to use him as a reliever.

All of that said, here’s the grand total of qualified seasons (162 innings pitched or more) by two-time Tommy John recipients after their second surgery: 2, both by Capuano.

Perhaps Taillon can add to this list, but he’s more likely to do it as a back-end starter, and he may be more effective, and more durable, in relief. All of which makes the collection of talented youngsters the Yankees sent to Pittsburgh for Taillon look more expensive than at first glance.

Of that lot, only Maikol Escotto is a lottery ticket. A teenage infielder from the Dominican Republic, Escotto has yet to play in the U.S., but tore things up in the Dominican Summer League as a 17-year-old in 2019. The other three are closing in on the majors, with one of them having already arrived.

That last is Miguel Yajure, a slender Venezuelan righty who will turn 22 in May and made his major-league debut with the Yankees last year. Yajure was a bit wild in the majors, and had only 11 innings above High-A prior to that, but he was able to miss major-league bats and has a deep enough repertoire (average fastball with a change, curve, cutter, and the occasional slider) that he could have a future in the Pirates’ rotation.

The other pitcher is 21-year-old Roansy Contreras, a skinny Dominican righty who held his own as a 19-year-old starter in A-ball in 2019 with a fastball/curve/change assortment. He could advance quickly given that he, too, is already on the 40-man roster. (Note: The Pirates designated outfielder Tony Stokes Jr., whom they had claimed off waivers from the Tigers earlier in the month, to make room for Yajure and Contreras on the 40-man.)

Finally, there’s outfielder Canaan Smith. Smith can rake. He hit an impressive .307/.405/.465 with 32 doubles, 16 steals (at an 80% success rate), and 74 walks in 124 games in A-ball in 2019. A fourth-round pick out of a Texas high school in 2017, he’ll turn 22 in April and should open this season in Double-A. If some of those doubles turn into homers, he could reach the majors by next year, if not sooner.

None of those youngsters are future stars, but they’re quite a bit better than organizational filler, which means the Yankees have made a real investment in Taillon’s ability to return to form.

Reds acquire LHP Cionel Pérez from Astros for C Luke Berryhill and RHP Héctor Pérez from Blue Jays for a player to be named later or cash

Cionel and Héctor Pérez share more than a last name. They will both be 25 this season. They both have limited major league exposure (20 games for Cionel, just one for Héctor) but did pitch in the majors last season. Both throw a slider and a mid-90s fastball, and both are former minor league starters who are likely to be limited to relief work in the majors due in part to serious control problems. It’s not hard to tell them apart in person, however. Dominican righty Héctor is several inches and a good 60 pounds larger than undersized Cuban lefty Cionel.

Luke Berryhill, no relation to former major league catcher Damon Berryhill, was a 13th-round pick out of the University of South Carolina in 2019. He was not at the Reds’ alternate training site last year, and thus has just eight professional games under his belt, all in 2019. Due to that lack of exposure, I can’t tell you much about his potential as a hitter or a catcher, but the Georgia native is a surprisingly good country singer:

Braves claim OF Kyle Garlick and RHP Víctor Arano off waivers from the Phillies

The Phillies designated these two for assignment a week ago to make room on their 40-man roster for shortstop C.J. Chatham, acquired from the Red Sox for a PTBNL, and free-agent reliever Archie Bradley. The Braves kept them in the division by claiming them on Friday. Garlick, who turns 29 this week, provides some outfield depth for a team that saw Marcell Ozuna, Nick Markakis, and Adam Duvall all hit free agency this winter (all three remain unsigned). Arano, who will turn 26 in early February, impressed out of the Phillies’ bullpen in 2018 (2.73 ERA in 59 1/3 innings), but was sidelined for all but 4 2/3 innings since due to surgery to remove a bone spur from his pitching elbow in 2019 and shoulder issues last year.

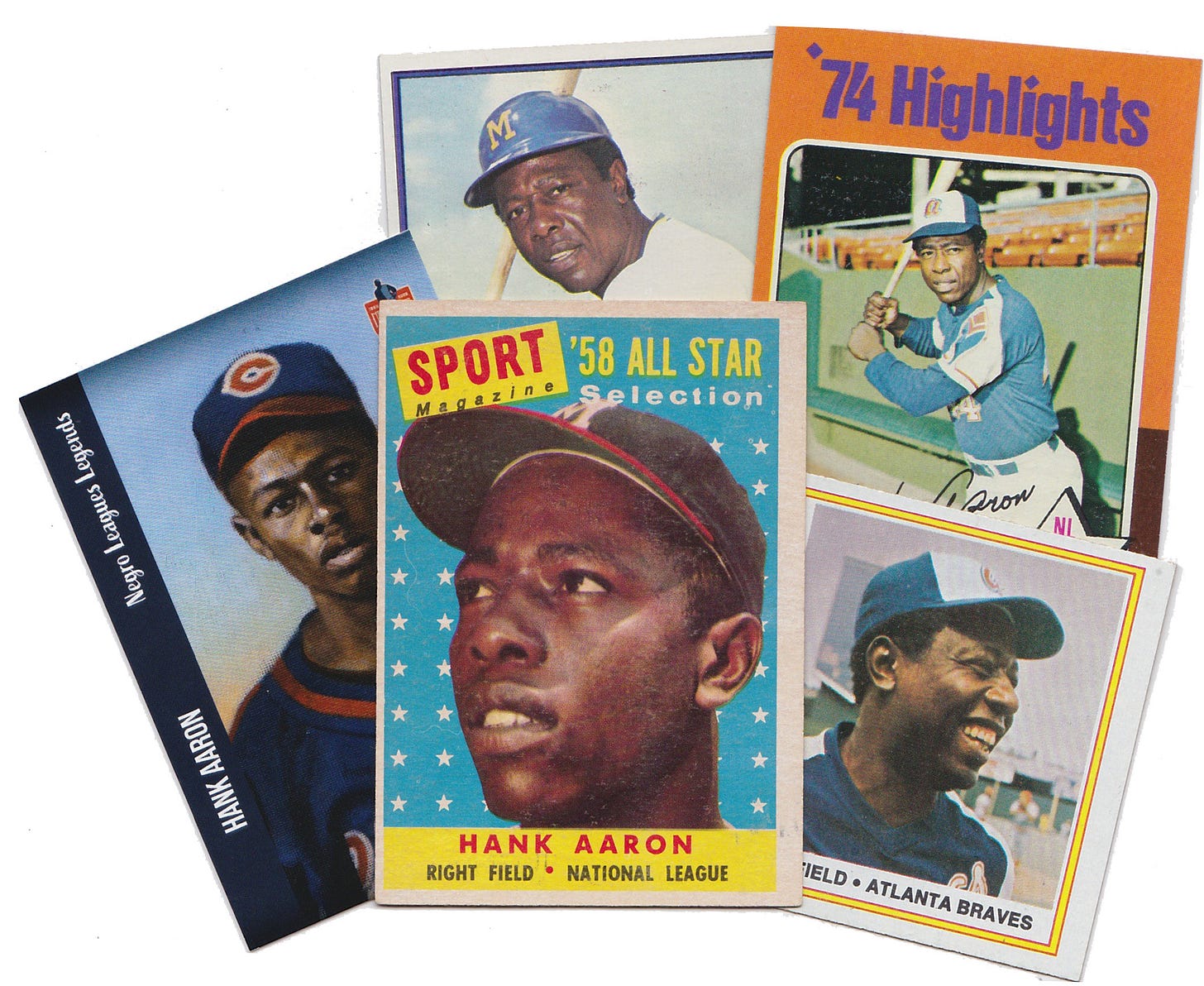

Hank Aaron (1934-2021)

Henry Louis Aaron died on Friday, exactly two weeks shy of his 87th birthday. The size of the loss is staggering. Aaron was among the most accomplished and admirable people ever to grace a professional baseball field. His experiences in the game stretched back to the waning days of the Negro Leagues. His contributions to the game towered over those of all but a select few. His example on and off the field continues to inspire people of all ages, backgrounds, and interests. All of that is true and widely recognized, and yet, Hank Aaron’s greatness somehow still feels underappreciated.

Henry Aaron was born in Mobile, Alabama on February 5, 1934, one of eight siblings in a poor black family in the Jim Crow south. Among those siblings was younger brother Tommie, who would also play and coach for the Braves until his death from leukemia in 1984. As a teenager, Henry played on local semi-pro teams before joining the Indianapolis Clowns of the Negro American League in 1952 at the age of 18. At that time, Aaron was a scrawny shortstop with a cross-handed batting grip. He fixed the grip when a scout, who had come to observe the Clowns for the Boston Braves, pointed it out in batting practice. Aaron hit two home runs in the subsequent game and, in his words, “never looked back.”

That June, the National League’s New York Giants and Boston Braves both attempted to sign Aaron away from the Clowns. According to his autobiography, I Had a Hammer (co-authored by Lonnie Wheeler, who died of a heart attack in July), the Braves offered a higher salary ($350 per week), and the Giants misspelled his last name in their telegram (“Arron”), so Henry chose Boston. The Braves gave Aaron a cardboard suitcase and a ticket for his first airplane ride, to join their Class C team in Eau Clair, Wisconsin.

Aaron was still a minor league second baseman when the Braves moved to Milwaukee in 1953, but, in Spring Training in 1954, Bobby Thomson, the Braves’ newly-acquired left fielder, broke his ankle, clearing the way for 20-year-old Henry to make his major league debut as Milwaukee’s Opening Day left fielder. Despite going 0-for-5 in his debut, Aaron never returned to the minor leagues. He had a good rookie season, finishing fourth in the National League Rookie of the Year voting. The next year, and for the better part of the next twenty years, he was great.

In his fourth major league season, Aaron won the National League’s Most Valuable Player award and, along with fellow future Hall of Famers Eddie Mathews and Warren Spahn, led the Braves to their first of two consecutive World Series appearances against the dynastic Yankees. Both Series went the full seven games. The Braves won the first, with Aaron hitting .393/.414/.786 with three home runs, a 450-foot triple, seven RBI, and five runs scored. They lost the second despite Aaron hitting .333 and reaching base 13 times in the seven games.

Aaron would never return to the World Series as a player. As the sixties progressed, the Braves aged, declined, and moved to Atlanta. Yet, they were never truly lousy, thanks in large part to Aaron. The Braves didn’t post a losing record with Aaron on the team until 1967, and that belated dip was despite Hank’s continued greatness. According to Baseball-Reference’s calculations, Aaron led the team in wins above replacement every year from 1956 to 1969 (and did so again in 1971).

Aaron’s consistency was one aspect of his greatness, but, in a way, it also masked it, as his production varied so little from year to year. From 1955 to 1970, Aaron never played in fewer than 145 games or made fewer than 634 plate appearances. From 1955 through 1973, he never posted an OPS+ lower than 141. His average season over that nineteen-year span saw him hit .312/.380/.574 (162 OPS+) in 642 plate appearances with 37 home runs, 109 RBI, 105 runs scored, 327 total bases, 12 stolen bases, and just 65 strikeouts. That performance, combined with his typically strong play in the outfield, was worth an average of 7.3 wins above replacement per year. From 1956 to 1969, a fourteen-year span, he averaged an even 8.0 bWAR.

Aaron made every National League All-Star team from 1955 through 1974, and made the AL team in 1975 at the age of 41, after the Braves traded him back to Milwaukee to finish his career as a designated hitter with the Brewers. There were two All-Star Games every year from 1959 to 1962, so, in total, he made 25 All-Star games in a 23-year career. Aaron also received MVP votes every year from 1955 through 1973, finishing in the top five eight times. He led his league in home runs, RBI, doubles, and slugging percentage four times each, in total bases eight times, runs thrice, hits twice, won two batting titles, and led the majors in OPS+ three times. When he retired, he held the career records for total bases (6,856), extra-base hits (1,477), RBI (2,297), games played (3,298), plate appearances (13,941), at-bats (12,364), and, of course, home runs (755). He still holds the first three of those records and ranks third all-time in hits (3,771) and seventh all-time in career bWAR (143.1) among all players, including pitchers.

Despite all of that, Hank Aaron was, and is, underrated as a player. Aaron’s signature moment came on April 8, 1974, when he broke Babe Ruth’s career record with his 715th home run. As a result, the image of Hank Aaron in uniform that most readily comes to mind for most fans is of a 40-year-old man trotting around the bases in a colorful double-knit uniform that is a bit snug around the middle. Largely forgotten is the sinewy young man with lightning-fast wrists in a baggy, wool Milwaukee Braves uniform.

Footage of the younger Aaron can be harder to come by, so here is his pennant-clinching home run from 1957, which came off the Cardinals’ Billy Muffett with Johnny Logan on first base and the score tied 2-2- in the bottom of the 11th on September 23 of that year:

Also, here’s the full at-bat, against Don Larsen, from his first home run of the 1957 World Series. This is from the original broadcast and thus a fairly low-quality image:

While I’m at it, here’s an interview with the 24-year-old Aaron from the following year’s Spring Training:

For higher-quality video, see these MLB.com clips of Aaron’s third homer from that Series (from the official World Series film, the entirety of which is available on YouTube), and this color footage of a home run he hit in June 1959. Sadly, I cannot embed MLB.com videos on substack.

That Hank Aaron, the one in the flannel, won three Gold Gloves in right field, played 308 games in center, and averaged 22 stolen bases at an 81 percent success rate from 1961-68 (the last three years, admittedly, as an Atlanta Brave). Aaron won his only MVP award in 1957, but a strong argument can be made for his candidacies in 1959, ’60, and ’61, as well. Speaking of which, good luck trying to determine his best overall season from his age-25 to -29 peak. In those five years, 1959 to ’63, Aaron averaged a 170 OPS+ and 8.8 bWAR per year, yet he finished no higher than third in the MVP voting in any of those seasons and made the top five only in ’59 and ’63.

So, yes, Hank Aaron hit a lot of home runs, but he didn’t just hit a lot of home runs, and he didn’t just accumulate career records. He was an all-around player who could run, field, hit for average (.305 career), and throw. He also hit .362/.405/.710 with six home runs in 17 career postseason games (adding the inaugural National League Championship Series in 1969, which saw the Mets sweep the Braves).

Aaron also wasn’t just a great baseball player. Aaron’s pursuit of Babe Ruth’s home run record was marked as much by the courage and poise with which he endured an onslaught of racist threats as by the accomplishment itself. I never had the privilege of meeting Aaron, but I’ve never heard a bad word said about the man, and never saw him conduct himself with anything other than dignity and class. He spoke slowly and carefully in a deep baritone with a slight drawl, and while he always projected a gentle demeanor, Aaron was not shy about describing the racism that confronted him at various points in his life and career, nor the pain that it caused him. Nor was he shy about speaking out about perceived wrongs when he felt his voice needed to be heard.

Consider this passage from his autobiography about the hate mail he received during his pursuit of the career home run record:

I asked Carla [his secretary] to save the hate letters that she didn’t have to turn over to the authorities. I didn’t read most of them, but I wanted to have them as reminders. I kept feeling more and more strongly that I had to break the record not only for myself and for Jackie Robinson [who died a year and a half before Aaron broke the record] and for black people, but also to strike back at the vicious little people who wanted to keep me from doing it. All that hatred left a deep scar on me. I was just a man doing something that God had given me the power to do, and I was living like an outcast in my own country. . . . I resented it, and I still resent it. It should have been the most enjoyable time in my life, and instead it was hell. I’m proud of the home run record, but I don’t talk about it because it brings back too many unpleasant memories.

Aaron’s greatness and grace dominate his legacy, as they should, but another important part of that legacy is the cruelty with which he was treated regardless of his station. As Aaron wrote in an essay commissioned by Robinson in 1964, a decade before his home run chase, “Baseball has done a lot for me . . . [but] it has taught me that, regardless of who you are and how much money you make, you are still a Negro.”

Aaron retired from baseball after the 1976 season and had been part of the Braves’ front office ever since. He was the team’s vice president in charge of player development from 1976 to 1989, a period that saw the major league debuts of Tom Glavine, Ron Gant, Jeff Blauser, John Smoltz, Mark Lemke, Mike Stanton, Kent Mercker, and David Justice, all of whom were part of the 1991 National League champions who initiated Atlanta’s record-setting run of division championships. From December 1989 until his death, Aaron served as a senior vice president, with a focus on charitable endeavors. His survivors include his wife of 47 years, Billye, four children from his first marriage, and Billye’s daughter, whom he adopted.

We shall not look upon his like again.

Author’s Note

Before I go any further, thank you for signing up for The Cycle. I put this introduction down here so that we could get right into the baseball up top, but I want to you to know how much I appreciate your interest in this newsletter (and the fact that you’ve read this far into it!). I launched The Cycle because, while I have continued to write steadily about baseball, for a variety of publications, since departing SI.com in late 2016, I haven’t had the opportunity to dig into the daily grind of the baseball season in the manner to which I am accustomed. I’m proud of the work I did for Sports on Earth, The Athletic, and others, some of which I’ll surely reference as we go along here, but when I started blogging about baseball way back in 2003, it was because I loved that ebb and flow of the season and the degree to which baseball rewards close examination. That is what I’m so excited to return to here.

Some prefer to view the game from ten-thousand feet, to focus on the big themes, historical resonances, and societal lessons that they can glean from baseball. I value those perspectives tremendously and will not hesitate to share something from that point of view here. However, my love of the game starts with the small stuff: parsing the results of a single game, contemplating the impact of a transaction or rule change, the beauty of a spectacular play, the details of a uniform, appreciating a player’s excellence, understanding his shortcomings, and determining how those things might influence a team’s fortunes.

This newsletter will focus, as much as possible, on the game on the field. I call it “your companion to Major League Baseball’s seasons” because my intention is for The Cycle to enrich your baseball-watching experience. My primary goal throughout my career as a baseball writer has been to answer two questions: “Why did this happen?” and “What does it mean?” My hope is that, when something interesting happens in baseball, you will turn to The Cycle for those answers.

I also hope that this newsletterwill serve as something of a viewer’s guide to the season as it progresses. The Cycle will publish Monday, Wednesday, and Friday, with the issues arriving in your inbox in the wee morning hours on those days. During the regular season, the Monday and Friday issues will include a look forward to key matchups in the week, or weekend, to come. I will also be looking forward in previews of Spring Training, the regular season, opinions on All-Star and Hall of Fame voting, evaluations of trade-deadline needs, more detailed previews of postseason matchups and games, and so on.

The degree to which I supplement that material with frivolities such as musings on uniforms, baseball cards, and pop culture (I spent half a decade as a music critic before starting my first baseball blog) remains to be seen, and will likely vary depending on the quantity of baseball news in a given issue and your feedback.

On that last point, it is very important to me that The Cycle is responsive to you, the reader. I do not have the comments open on Substack, but I encourage you to email me with questions, comments, criticisms, or corrections. It’s my hope that, as The Cycle finds its feet, an ongoing conversation with you and the readership at large becomes part of it.

You can reply directly to each issue, or email cyclenewsletter@substack.com. I want to hear from you. I might respond to your email directly, reply to it in the newsletter (I’d love to have a reader mailbag as a regular feature), or even use it as the launching point for larger piece, but I will respond, and I will bear your comments, requests, and criticisms in mind as The Cycle takes shape.

Most likely, the newsletter’s content and format will evolve over time, not unlike the first season of Saturday Night Live (though, I’m sorry to say, I won’t be able to stage a Simon & Garfunkel reunion to give myself a breather). It may also change as we proceed through the stages of the baseball season. Indeed, that progression was the primary inspiration behind the name. I chose “The Cycle” to evoke the manner in which the yearly cycle of the baseball season echoes the annual cycle of the four seasons. Those four seasons are represented in the logo by the four hits required to hit for the cycle.

A note on “politics”: The U.S. House of Representatives will transmit its articles of impeachment to the Senate today, but you won’t read any more about that here. That’s not why you came here, and it’s not what I came here to do. As anyone who follows me on twitter (@CliffCorcoran) knows, I make no secret of my political opinions (I’m a progressive who voted and volunteered for Elizabeth Warren in last year’s primary). However, as important as I think political activism is, that is not the intended purpose of this newsletter.

A huge part of the appeal of sports is as a diversion, a release, and a confined space that offers the illusion of an order, control, and fair play. Whether or not I was aware of it, I suspect that was a significant part of what drew me to baseball, and sports in general, around the time of my parents’ divorce. With the United States’ executive branch back in the hands of responsible, capable people with good intentions, I would like to keep the focus here on the game and other frivolities, and for this to be a place of positivity, camaraderie, and escape.

That said, the outside world will intrude, be it because of a national or international crisis such as the pandemic, or because of the actions of individuals in and around the game. When the baseball discussion breaches those topics, I will not hesitate to weigh in, but I will try not to get bogged down. One cannot stick to sports when sports bleeds over its supposed boundaries (which are illusory to begin with). Still, I do not intend to use this newsletter as a soapbox.

Reader Survey

Getting back to you, my dear reader. In order to serve you better, I would like to know a little more about you. This is optional, of course, but, if you don’t mind, please reply to this issue with:

your favorite team (or teams, or if you are a general-interest baseball fan)

your general location (as many of the following as you feel comfortable sharing: city, state, province, country for those outside the U.S. and Canada)

your birth year (because it doesn’t change, unlike your age)

The idea here is to know whom I’m writing for, what teams you want to read about, and when and where you’ll receive the newsletter. I can’t promise I’ll write more about, say, the Pirates if you tell me you’re a Pirates fan, but if there’s a large Pirates contingent among the readership, I will likely lower my threshold for including Pirates items and dive deeper into the ones I include.

Closing Credits

Okay, there are no closing credits. I wrote and edited every word of this issue. (Nearly 10,000 of them! Future issues should be shorter. I had too much time to prepare this one.) I conceived of and created the name and logo. I arranged and scanned in the baseball cards from my own collection. It’s all me: Cliff Corcoran. However, I like the idea of leaving you with a song, and I like it even more if you think of it as the music that would play behind the closing credits, if we had any. So, at least to start, “Closing Credits” will be the outro music for each issue.

We start today with what some might consider an obvious choice. It’s the song my good friend Steven Goldman mentioned off the top of his head when we discussed The Cycle on Steve’s “The Infinite Inning” podcast two weeks ago: XTC’s “Season Cycle.” If you read this far without skipping ahead, you can guess why just from the title.

“Season Cycle,” written by Andy Partridge, XTC’s guitarist and principle songwriter, closed side one of what many consider the British psychedelic-pop trio’s best album, 1986’s Todd Rundgren-produced Skylarking. Musically, it’s sort of a jaunty take on Smile-era Beach Boys. Lyrically, it’s about the cycle of the seasons and the mystery of what created all of this and propels us forward, the last of which reveals that the title is a pun. Here’s the key bit:

Darling, don’t you ever sit and ponder (Darling, did you ever think)

About the building of the hills a yonder (All this life stuff’s closely linked)

Where we’re going in the verdant spiral

Who’s pushing the pedals on the season cycle?

The Cycle will return on Wednesday with a reaction to the Hall of Fame vote (results will be announced Tuesday evening on the MLB Network as part of a show that starts at 6pm EST) and a look toward next year’s ballot, among other things.

Enjoy! And please help spread the word about The Cycle!