The Cycle, Issue 116: Dead Men Tell Ball Tales

On the six new Hall of Famers elected by the Eras committees and nine major leaguers we lost over the last two months

In this issue of The Cycle . . .

Housekeeping: The Cycle is taking an extended holiday pause

The Hall of Fame: The eras committees name six new inductees

In Memoriam: Eddie Robinson, Don Demeter, Bill Virdon, Ray Fosse, Jerry Remy, LaMarr Hoyt, Doug Jones, Ricky Nelson, and Ron Blazier

Feedback

Closing Credits

Housekeeping

First, my apologies for the late arrival of this issue.

Second, it’s going to be even longer until the next one, as The Cycle will be taking an extended pause for the holidays and, potentially, much of January. The extended part is, in part, because I’m going to be doing some behind-the-scenes work on a couple of Baseball Prospectus books over the next six weeks or so, and I need to make sure I hit my deadlines on those projects.

I will continue writing the free MLBTR Newsletter on Monday through Friday mornings (minus, I assume, a couple of holiday-related time-outs), so you can get my quick takes on the latest baseball news, what little of it there is likely to be, there. In the meantime, I’ll pause all subscriptions here until The Cycle resumes, so no one will be charged during this pause in the action.

I’m assuming that the MLB lockout will outlast this pause, so it’s unlikely that much of significance in the baseball world will happen during this time-out. The next major event on the baseball calendar is the announcement of the results of the BBWAA’s Hall of Fame voting on January 20, by which point The Cycle should be back in action to react to those results and celebrate its first anniversary (on January 25!).

That makes this the last issue of 2021, and possibly of The Cycle’s first year. So, I just want to say, once again, thank you to all of you for reading, subscribing, participating, and supporting The Cycle this year. I wish you all happiness and health, always, and a full, 162-game MLB season in 2022!

The Hall of Fame

Last Sunday, the Hall of Fame’s Early Baseball and Golden Days Committees met in Orlando, Florida, the site of the partially cancelled winter meetings, and elected six new members of the National Baseball Hall of Fame. Both committees consisted of 16 members, some overlapping, each of whom had four votes they could distribute among the 10 candidates on their respective committee’s ballot. Each candidate needed 75 percent of the committee’s support, or 12 votes, to gain induction.

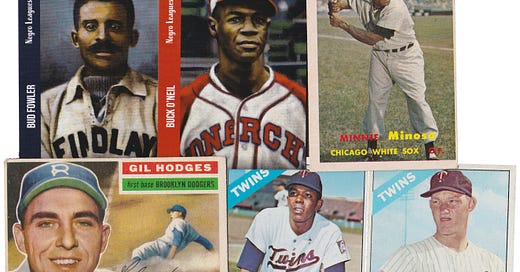

The Early Baseball Committee, presented with a ballot with nine arguably deserving candidates, elected two, Negro Leagues icon Buck O’Neil and Black baseball pioneer Bud Fowler. O’Neil and Fowler were indeed, in my estimation, the two most deserving candidates on the ballot.

The Golden Days Committee, presented with a ballot that was a bit more of a mixed bag, managed to elect four of the 10: White Sox great Minnie Miñoso, by far the most deserving of the 10; Gil Hodges, who, in addition to his accomplishments on the field, was the candidate who had received the most support on the writers ballot (63.4 percent in his final year on the BBWAA ballot) without eventual induction (that distinction could be passed on to Curt Schilling if he falls short in this, his final year on the BBWAA ballot); and former Minnesota Twins teammates Tony Oliva and Jim Kaat. Dick Allen fell one vote shy.

That Golden Days Committee result reveals an extraordinary amount of coordination on the part of the committee members, as 61 of the 64 possible votes went to just five candidates. In December 2017, The Athletic’s Jayson Stark was on the Modern Era Committee that elected Alan Trammell and Jack Morris, and he discussed the experience and the process later that month on Ross Carey’s Replacement Level Podcast. That episode is an essential listen for anyone interested, or frustrated, about how these committees work. Here’s the key bit from Stark, which could help explain how this year’s Golden Era Committee managed to be so successful:

I can’t speak for how everyone voted, but I did get the sense that there were a lot of people in the room like me. They were trying to read the room. I went in there with the names of people I was virtually certain I was going to vote for, but then the dynamic in the room was such that, again, that weight of making every vote count had an impact on how I filled out my ballot. When you get to that last name, you’re thinking to yourself, ‘okay, who do I think has a real chance here.’ Even if I think Player X is more deserving, I also think Player Y is a Hall of Famer, and so many people in the room seem to think that, I’m going to vote for Player Y instead of Payer X.

The ballots are secret, and there is no second round of voting to get someone like Allen that one missing vote, but that concept of reading the room and trying to form, or at least detect, a consensus in the discussion that precedes the vote goes a long way toward explaining the efficiency of this year’s Golden Days committee vote, as well as the productivity of the Eras committees in general over the last five years.

Before Stark’s committee elected Trammell and Morris, the veterans committees, in their various forms, had not elected a living player in 16 years. They did induct various living managers and executives, but the Negro League Committee stiffed Buck O’Neil mere months before his death in 2006 and elected Ron Santo almost exactly one year after his death in December 2010. Though both are now rightly in the Hall, their inability to enjoy their deserved inductions during their lifetimes still stings, and likely always will.

The current eras committee format was put in place after Santo was snubbed for the last time by the 2009 Veterans Committee, the fourth time in seven years that he was on the ballot but not elected. The format was further tweaked in 2016, expanding the scheme from three committees to four. Since 2017, those Committees have excelled at electing living players, and this year’s Golden Era result suggests that a focus on living players has become a priority if not an outright mandate for the committees on which living players have appeared, as two of the three living players on the ballot (Maury Wills was the third) were inducted.

Since 2017, the Eras committees have elected Trammell, Morris, Lee Smith, Harold Baines, Ted Simmons, Tony Oliva, and Jim Kaat, all alive to hear the news. They have also righted the long-time omissions of Marvin Miller and now Buck O’Neil, Minnie Miñoso, Gil Hodges, and Bud Fowler, all deceased. Of that lot, I’m thrilled that Miller, O’Neil, Miñoso, Fowler, and Trammell are finally in. I’ll admit to having a soft spot for Hodges, too, though there is definitely some regional bias there given that his candidacy hinged largely on his accomplishments with the Brooklyn Dodgers and Mets. I’m less sanguine about Oliva, Smith, and Simmons, borderline candidates whose inclusion in the Hall neither diminishes nor improves it, in my opinion. Kaat, Morris, and Baines, however, just don’t belong, at least not to my eye.

All of that prompts this question: Is it better to induct the occasional Jim Kaat or Harold Baines if it’s part of a process that opens the door wide enough for the O’Neil, Miñoso, and Millers of the world, and if it means that more inductees will be alive to enjoy it, or was it better to keep the Hall more exclusive even if it meant letting deserving inductees go to their grave without the honor?

Seeing those words in print, I don’t think there’s much question that the former is preferable. I say that as someone who leans toward a bigger Hall in general, and who isn’t entirely blind to the arguments for Kaat and company. Jim Kaat, for example, was never a dominant ace, but the list of pitchers who pitched for 25 years, had 13 seasons with both 200 innings pitched and an ERA+ above league average, and won 16 Gold Gloves consists of only him, and only 15 other pitchers have done the 200-innings/above-average ERA+ thing as many or more times, with only Roger Clemens (15 times) still outside of the Hall. Kaat also had a long and mostly distinguished career as a broadcaster (his offhandedly racist comment in this year’s Division Series aside; that’s a whole other conversation).

In writing about this year’s ballots in Issue 110, I listed Miñoso, Allen, Hodges, and Oliva as the four candidates I’d put in first of the six I thought were deserving from the Golden Age ballot (Kaat was not among the six, but Ken Boyer and Billy Pierce were). Thus, of the six men elected last weekend, five of them are players I would have voted for if I had the chance. The Hall of Fame’s selection process is never going to be perfect, in part because everyone’s idea of perfect is different from everyone else’s, but the current eras-committee format does seem to be far more effective, at least for big-Hall types like myself. So, whatever objections I might have about Kaat or even Baines, I’ll skip them for now. Congratulations to this year’s inductees and their families.

In Memoriam

Obituaries have been a running feature of The Cycle from the very beginning, as I have always tried to honor a player’s life and career on the occasion of his death. Unfortunately, three major figures—Eddie Robinson, Ray Fosse, and Jerry Remy—died in October, when my postseason coverage kept me too busy to give them the attention they deserved. Since this week’s top story centers on honoring players’ careers, as well as on the mortality of those players, this seemed like an appropriate time to go back and honor those three, as well as some of the others I have missed in recent weeks, and those who have passed more recently.

Unfortunately, as has always been the case in this newsletter, this is not a comprehensive accounting of those the baseball community has lost over the last couple of months. For a more complete compilation of baseball obituaries, I recommend RIP Baseball, which is maintained by SABR member Sam Gazdziak. In some cases, Sam’s obituaries, as well as the invaluable SABR biographies, have informed the below.

Eddie Robinson (1920–2021)

Prior to his death on October 4 at the age of 100, Eddie Robinson was both the oldest living major leaguer and the only surviving member of the last Cleveland team to win the World Series. As a player, Robinson was a four-time All-Star first baseman who hit .268/.353/.440 (113 OPS+) with 173 home runs and 1,146 hits across 13 seasons, winning the World Series as Cleveland’s starting first baseman in 1948 and losing it as a left-handed bench bat with the Yankees in 1955. That’s a fine career, but Robinson loomed even larger as a Zelig-like figure who spent 65 years in baseball and was an eyewitness to much of the game’s history over that span.

Born in Paris, Texas, in December 1920, Robinson began his professional baseball career in the Pirates’ organization in 1939 at the age of 18. He made his major-league debut with Cleveland in September 1942, but spent the next three years in the Navy, though, like many players, he never left the United States while in the service.

In 1946, Robinson returned to the triple-A Baltimore Orioles in the International League, which just happened to be the first integrated league in the twentieth century. With Baltimore, Robinson played against Montréal’s Jackie Robinson and beat Jackie out for the league’s MVP by hitting .318/.405/.578 with 34 homers and 123 RBI (Jackie hit .349/.468/.462 with 40 steals and 113 runs scored). Eddie returned to the majors that September. In 1947 he was teammates with the Larry Doby as Doby became the first Black player in American League history.

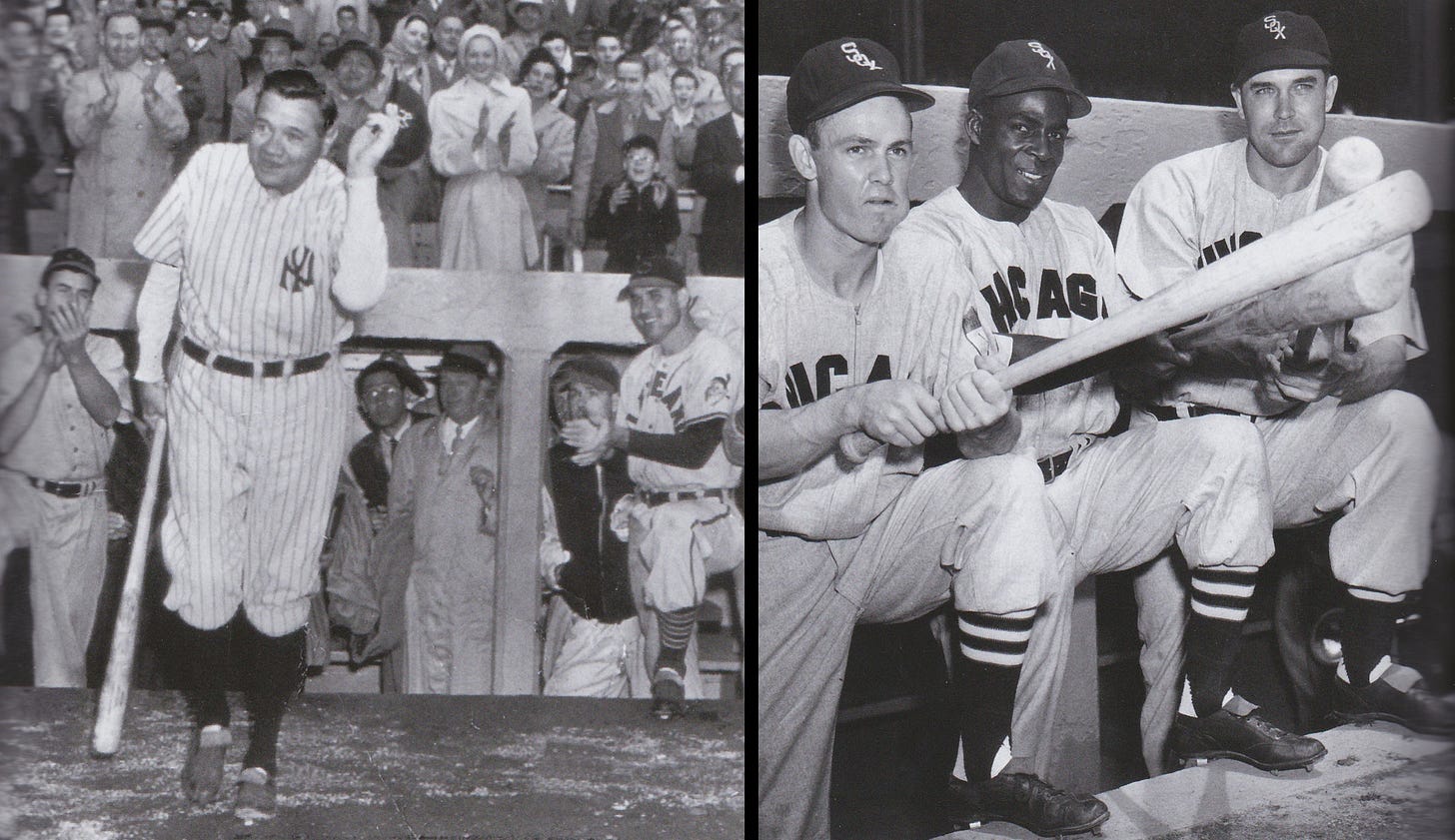

In 1948, Robinson and Doby were both regulars in the Cleveland lineup as Cleveland won the pennant and the World Series that remains the most recent in franchise history. In June of that year, Cleveland was in New York to play the Yankees on the day that Babe Ruth’s number was retired. That was the day this famous picture of Ruth, in uniform for the last time, was taken. The bat Ruth is leaning on is Robinson’s (you can see Robinson cheering on Ruth as he leaves the dugout with his bat in the photo on the left above). Less than a month later, Robinson and the rest of the Cleveland team got a new teammate: Negro Leagues legend Satchel Paige.

When Robinson was a youngster with Cleveland, the team employed Tris Speaker and Rogers Hornsby as Spring Training instructors, and Robinson got to pick Hornsby’s brain about hitting. As Robinson’s career progressed, he played for every original AL franchise except the Red Sox, and was thus teammates with nearly every great American League player of the 1950s except Ted Williams, who visited him countless times at first base. Robinson also played for nearly every notable AL manager of the era, including Hall of Famers Casey Stengel, Al Lopez, Bucky Harris, and Lou Boudreau (with both Cleveland and the Kansas City Athletics), though Robinson’s one year with the Philadelphia A’s came after Connie Mack’s retirement.

Robinson’s last major-league manager, with the 1957 Orioles, was Paul Richards, who was also general manager of Baltimore at the time. Richards took Robinson under his wing as a coach and scout, and Robinson helped Richards lay the foundation of the great Orioles teams of the late ’60s. In 1961, Richards and Robinson became the first general manager and assistant GM, respectively, in Houston Colt .45s/Astros history. The two collaborated on acquiring players such a Joe Morgan, Jim Wynn, and Rusty Staub. After the 1965 season, Astros owner Judge Hofheinz fired Richards, so Robinson reached out to his former Yankee teammate Eddie Lopat, who was then the GM of the Kansas City Athletics, for a job. A’s owner Charlie O. Finley hired Robinson as Lopat’s assistant GM that winter, and there Robinson was instrumental in drafting Reggie Jackson.

After a year with the A’s, Richards, who had caught on as the Braves GM, hired Robinson away as the Braves’ farm director. In 1972, Robinson succeeded Richards as the Braves’ GM, a position he held throughout Hank Aaron’s pursuit of Ruth’s home-run record, thus Robinson was present for both the retiring of Ruth’s number 3 and Aaron’s 715th home run. It was Robinson that traded Aaron back to Milwaukee after the 1974 season, and Robinson remained as GM after Ted Turner’s purchase of the Braves in 1976.

In 1977, the Rangers’ Brad Corbett hired Robinson as GM, bringing Robinson back to his home state. Before Robinson left, Turner asked him to recommend a successor. Robinson recommended his assistant GM, Bill Lucas, whom Turner subsequently promoted to become the first Black general manager in AL/NL history.

Robinson lasted in Arlington until 1982, when new owner Eddie Chiles fired him. George Steinbrenner immediately offered Robinson the Yankees’ GM job, but Robinson, now in his fifties and finally back home in Texas, opted to stay home and take a position as a special assistant to the Yankees temperamental owner. For those not keeping track, Robinson thus held front-office positions for George Steinbrenner, Charlie Finley, Ted Turner, Judge Hofheinz, and Brad Corbett, among others. He also played for Bill Veeck in Cleveland and Clark Griffith in Washington.

After three years with Steinbrenner, Robinson went independent as a scout and player evaluator, working for ten different teams and contributing to the 1987 and ’91 Twins and 1990 Reds’ championships. After retiring in 2004, he lobbied for and helped win pensions for major-league players who hadn’t qualified due to the higher standard for vesting prior to 1979. In 2011, the same year that victory was secured, he released his autobiography, Lucky Me: My Sixty-Five Years in Baseball, which I recommend. Last year, just before his 100th birthday, he started a podcast, The Golden Age of Baseball with Eddie Robinson, and recorded 25 episodes, most between 10 and 20 minutes long, before he passed.

A few years ago, when I realized that Robinson was the last man alive who had won a World Series with Cleveland, I got it in my head to interview him. I bought and read his book, contemplated lines of questioning, and even pitched the idea as a possible episode of The Infinite Inning, but then I balked. I knew Robinson had been sharp and active well into his nineties, but I wasn’t sure how he was doing at the time, how much of a strain an extended interview would be on him, how easy a phone interview would be (this was before Robinson started his podcast), and didn’t want to seem like I was circling him like a vulture or to be a reminder of how close he was to the end. All of those concerns, save perhaps the last, proved to be unfounded. By all accounts, Robinson was in good form right up until the end and loved to share his experiences.

This wasn’t the first time I failed in this regard. I had the idea to interview my grandparents before they died and, as a journalism student at the time, was even asked to interview my maternal grandfather by his church, but I never did. I had that in mind when contemplating interviewing Robinson, but the latter only felt more intrusive, as I’m not a part of Robinson’s family, nor part of his legacy.

I share this here not to berate myself or to make this tribute to Robison about myself, but to remind those reading this that, when someone dies, their memories go with them. Making an effort to get those memories on tape or on the page honors them, and asking flatters them. Most would love to tell their story, even if they have to do it in short spurts, like Robinson did on his podcast, rather than marathon sessions. Don’t be like me. Interview your elders. Get their memories, thoughts, and ideas on tape. Thankfully C. Paul Rogers III, Robinson’s ghostwriter, and Greg Ricks, the producer of his podcast, didn’t make the same mistake with Robinson that I did.

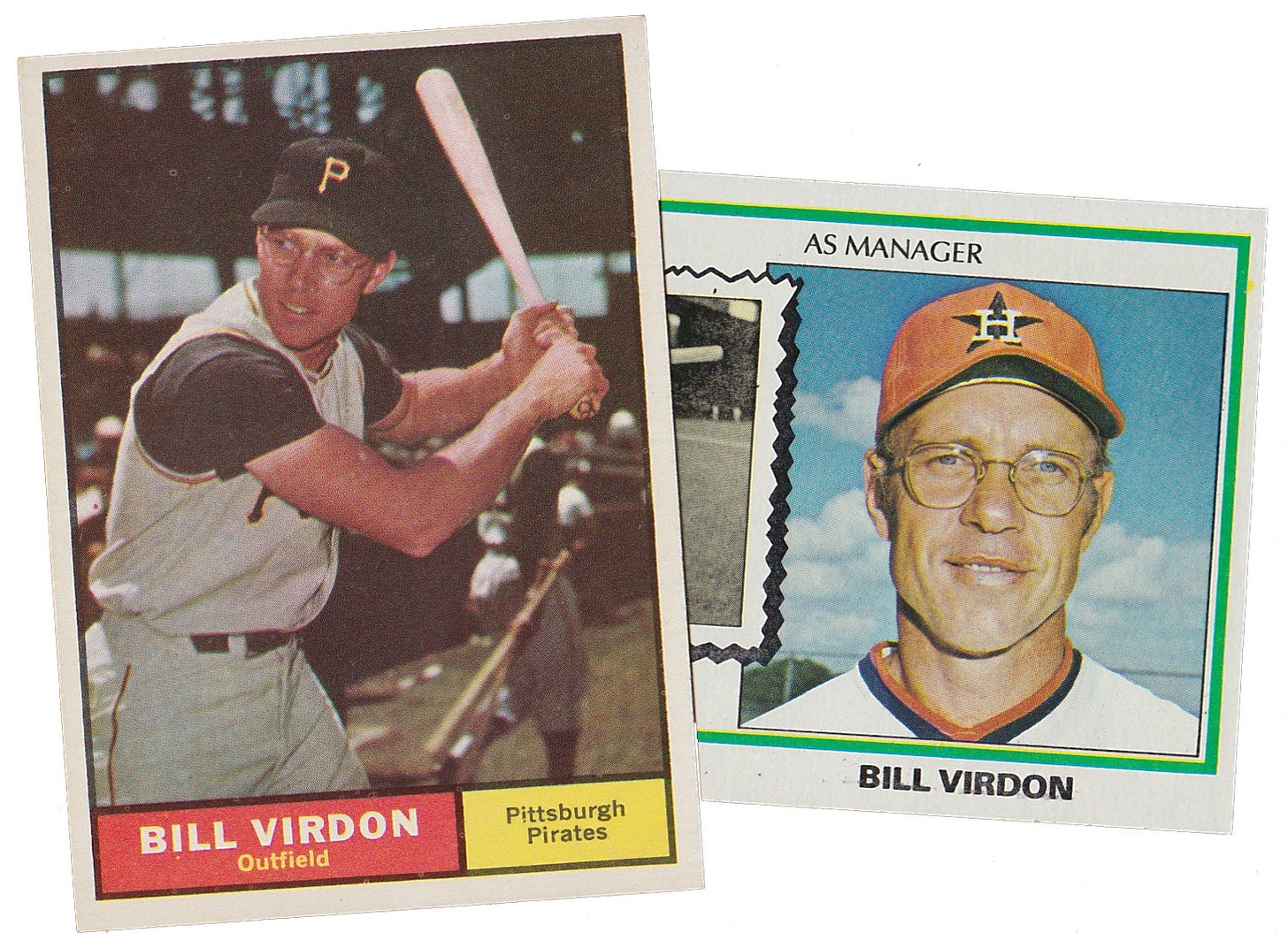

Bill Virdon (1931–2021)

Raised in the suburbs of Detroit, Michigan, and Springfield, Missouri, Bill Virdon attended a Missouri high school that did not have a baseball team. However, he played pick-up games as a kid and, in the summer after his junior year, travelled nearly 300 miles to play for the Clay City, Kansas, American Amateur Baseball Congress team. The next summer, he tried out for the Yankees and landed a contract with a $1,800 bonus.

The Yankees organization was brimming with talent in those days, so it was to Virdon’s advantage that he was one of three players sent to the Cardinals in the April 1954 trade that brought Enos Slaughter to the Bronx. In 1955, at the age of 24, Virdon won the NL’s Rookie of the Year award with his hometown Cardinals, hitting .281/.322/.433 (100 OPS+) with 17 home runs. Despite that solid debut, he was flipped to the Pirates the following May, after struggling to start the season. Virdon would go on to have the best season of his career at the plate in 1956, hitting .334/.374/.462 (127 OPS+) in 133 games for Pittsburgh with a 118 OPS+ overall.

Virdon’s actual player profile was that of a light-hitting, slick-fielding centerfielder. The slim, bespectacled Virdon managed a mere 85 OPS+ over the remainder of his 12-year career, but he was plenty valuable for his play in the field. He was a three-win player for the 1960 champions per Baseball-Reference’s metrics (and it was his would-be-double-play ball that hit Tony Kubek in the throat in the eighth inning of that year’s legendary Game 7, setting the stage for a five-run inning). Virdon won a Gold Glove in 1962, when he led the league in triples (and the majors in times caught stealing going 5-for-18 on the season), and remained a regular through his age-34 season in 1965.

Virdon retired after the 1965 season and went to manage in the Mets’ system. As a coach with the Pirates in 1968, he appeared in six more games as a player, going 1-for-3 with a home run. In 1972, he was made the manager of the defending champion Pirates and guided them back to the postseason only to lose the best-of-five NLCS to the Reds on a walkoff wild pitch in Game 5.

Shaken by the death of Roberto Clemente, the 1973 Pirates struggled to stay above .500. Virdon was fired with just 26 games left in the season, but he would helm one team or another for 13 straight seasons from 1972 through 1984, posting a career record of 995-921 (.519). In 1974, he managed the Yankees to a second-place finish and was named the AL Manager of the Year by The Sporting News, but George Steinbrenner, undeterred by his suspension from baseball at the time, fired the low-key Virdon in favor of Billy Martin in August of ’75.

Virdon’s longest managerial tenure was with the Astros, who snapped him up before the 1975 season was over. In 1979, Virdon’s Astros went 89-73, the best record and highest finish (second) in franchise history. In 1980, Virdon managed Houston to its first postseason, again losing a heartbreaking NLCS, this one to the Phillies in extra innings in Game 5. In the bifurcated strike season of 1981, Virdon’s Astros were the second-half NL West Champions but lost the Division Series to the Dodgers in five games as former Astro Jerry Reuss outdueled Nolan Ryan and shut Houston out in Game Five. The Astros fired Virdon after 111 games in 1982. After just shy of two full seasons with the Expos in 1983 and ‘84, his managerial career was over at the age of 53.

Virdon spent the next 17 years as a coach and instructor with the Pirates, Astros, and Cardinals before retiring at the age of 70, though he continued to attend spring training with the Pirates in his retirement. Virdon died on November 23 at the age of 90. He is survived by his wife of 70 years, Shirley, three daughters, seven grandchildren, and 13 great-grandchildren.

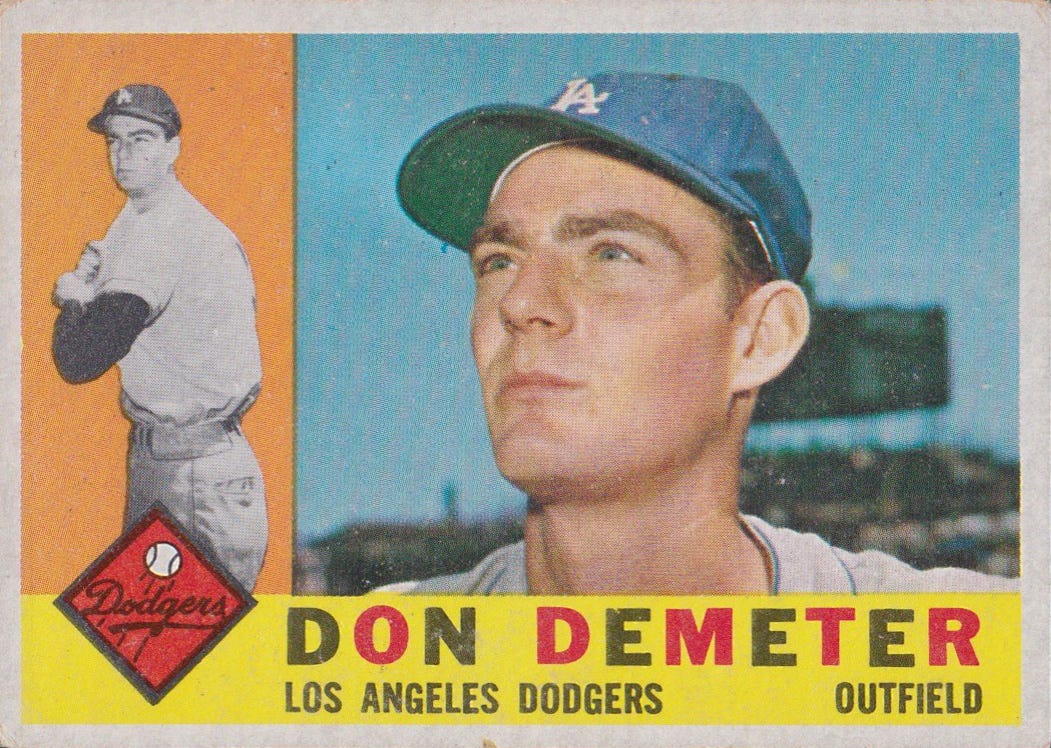

Don Demeter (1935–2021)

Don Demeter (accent on the first syllable) spent parts of 11 seasons in the majors, primarily as a centerfielder for the Phillies, Tigers, and Dodgers. A tall, lean righty from Oklahoma City, he was one of 11 boys from his high school team to sign professional contracts, nine of them with the Brooklyn Dodgers (the school’s coach was a scout for Brooklyn), but the only one to reach the majors. The starting centerfielder for the 1959 World Series champion Los Angeles Dodgers at the age of 24, Demeter had his best seasons after a May 1961 trade to the Phillies. In 1962, at the age of 27, he hit .307/.359/.520 (137 OPS+) with 29 homers and 107 RBI and finished 12th in the National League’s MVP voting. Over the next three years, he hit .263/.307/.451 (112 OPS+), averaging 20 homers a year and picking up a few more MVP votes in 1963.

Those three years spanned a trade to the Tigers in December 1963, and the latter part of Demeter’s career was most notable for his going the wrong direction in notable trades. That 1963 trade sent future Hall of Famer Jim Bunning and slugging catcher Gus Triandos to the Phillies. At the 1966 trading deadline (which was in mid-June back then), Demeter went from the Tigers to the Red Sox, netting righty Earl Wilson for Detroit. In June 1967, the Impossible Dream Red Sox sent him to Cleveland for righty Gary Bell. Demeter was humble and forthright about the reality of those trades. As Demeter told historian Bill Nowlin in 2006, “I tell Gary Bell this a lot when I see him at golf tournaments. Had [the Red Sox] not traded me and got Gary, I don’t think they would have won [the pennant]. Gary won 12 games for them. That’s exactly the truth. He helped them far more than I would have.”

Nagging injuries, declining performance, and an irregular heartbeat ended Demeter’s career at 32 after the 1967 season. He solved the heart problem with a change of diet and went on to found a swimming pool installation company back home in Oklahoma City and became a Baptist pastor at his local church. Demeter died November 29 at the age of 86.

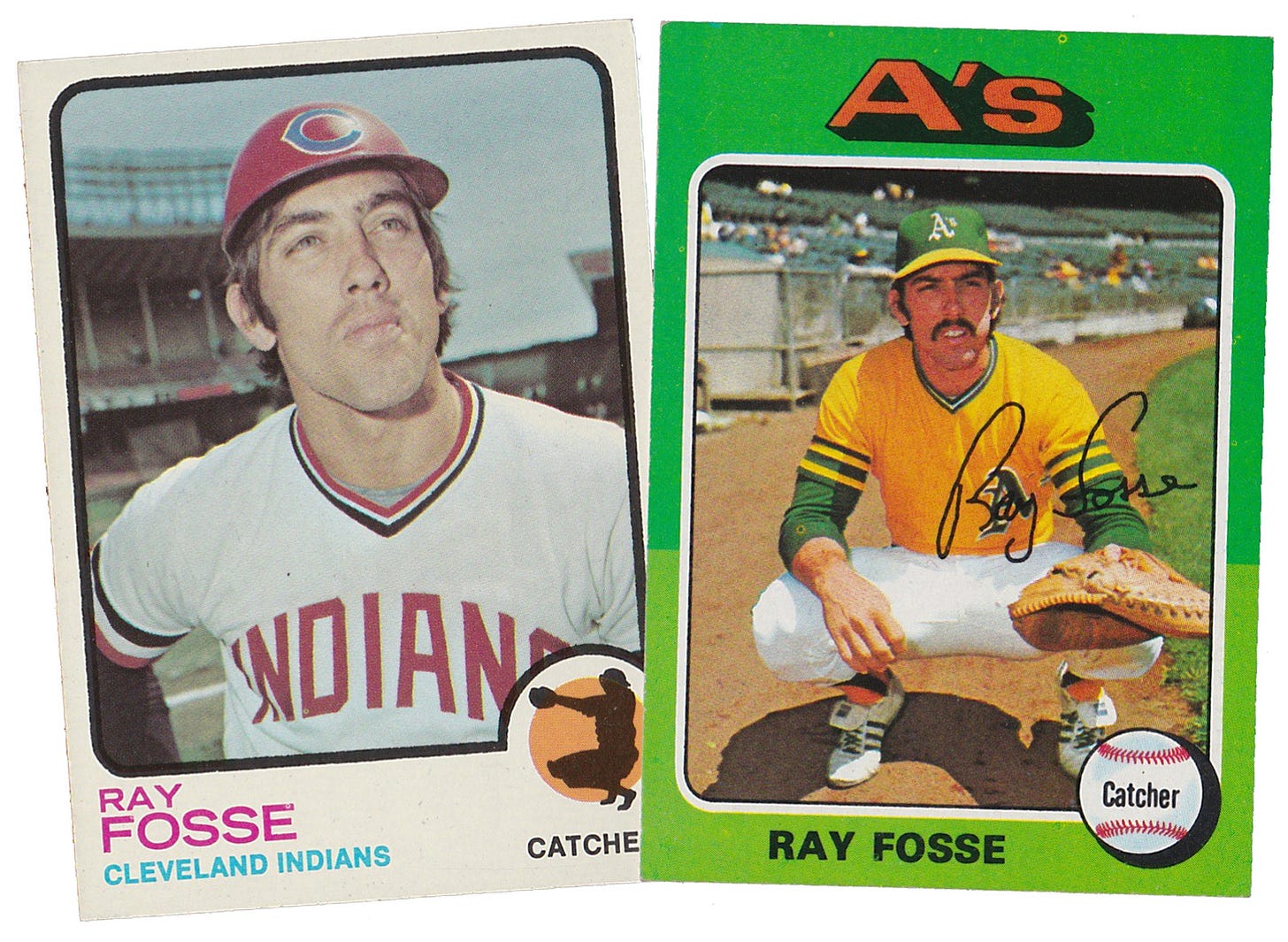

Ray Fosse (1947–2021)

There is a widespread belief that Ray Fosse’s career as a power-hitting catcher was derailed when Pete Rose blew up his left shoulder in the process of scoring the winning run in the 1970 All-Star Game, a famous play that Fosse would embrace as part of his legacy in the game. I’m not convinced. Yes, Fosse slugged .527 with 16 home runs in the first half of the 1970 season and just .361 with two homers in the second half. Yes, Rose did major damage, fracturing and separating Fosse shoulder, injuries which were masked by swelling on the initial x-ray and not detected until the following season. And, yes, Fosse slugged just .355 over the remainder of his career. However, Fosse didn’t hit for much power before the first half of 1970 either. I don’t doubt that the shoulder injury diminished Fosse’s career to some degree, but I don’t think it prevented Ray Fosse from being the next Johnny Bench.

Even without much power, Fosse was a very good player. The seventh-overall pick in the first amateur draft in major-league history in 1965, he was a heralded prospect from Marion, Illinois who first reached the majors in 1967 at the age of 20. Fosse didn’t secure the regular catching job in Cleveland until that fateful 1970 season. An outstanding defender, he won the Gold Glove and made the All-Star team in both 1970 and 1971, hitting .276/.329/.397 (98 OPS+) in the latter season.

Fosse didn’t get to play in the 1971 All-Star Game, not because of the shoulder injury, but because he tore a ligament in his left hand. That was after Fosse charged the mound against the Tigers’ Bill Denehy and suffered a laceration on his right hand that required five stitches. Despite all of those injuries, Fosse played in 253 games in those two seasons, only shutting it down in 1970 after a foul tip fractured his right index finger in early September.

Cleveland traded Fosse to the defending champion Oakland A’s just before the 1973 season, and Fosse served as the A’s primary catcher as they repeated as champions that season. From 1970 through ’73, Fosse averaged 3.2 bWAR per season despite that lack of power and his roughly league-average production at the plate. Thereafter, his playing time diminished due to a combination of injury and decline.

Fosse won another title with the A’s in 1974, but he missed 73 games mid-season after suffering a pinched nerve while trying to break up a clubhouse fight between Reggie Jackson and Bill North. That absence gave Gene Tenace an extended look behind the plate, and the A’s decided they preferred Tenace’s bat back there in 1975, moving Joe Rudi to first and installing 20-year-old Claudell Washington in left (Tenace and Washington both made the All-Star team in 1975, but the A’s lost the ALCS to the Red Sox).

Sold back to Cleveland for the 1976 season, Fosse had his best year at the plate since 1970 (.301/.347/.362, 110 OPS+ in 300 PA). In 1977, Fosse caught Dennis Eckersley’s no-hitter, but Cleveland traded him to the expansion Mariners in September 1977.

That December, Fosse signed a four-year deal with the Brewers covering his age-31 to -34 seasons, but he only managed to play 19 games for Milwaukee. In his first Spring Training with the Brewers, Fosse tore the lateral collateral ligament in his right knee and missed the entire 1978 season. Effectively the third-string catcher in 1979, he was released at the end of Spring Training in 1980, on the day before his 33rd birthday, and retired.

In 1986, Fosse started doing color commentary and pre-game hosting on the A’s radio broadcasts. Over the next 36 years, he became a beloved fixture on the A’s television and radio teams. To multiple generations of A’s fans, Fosse’s time in the booth eclipsed his career on the field. Fosse died on October 13 at the age of 74 after a 16-year battle with cancer. His survivors include his wife, two daughters, and two grandsons.

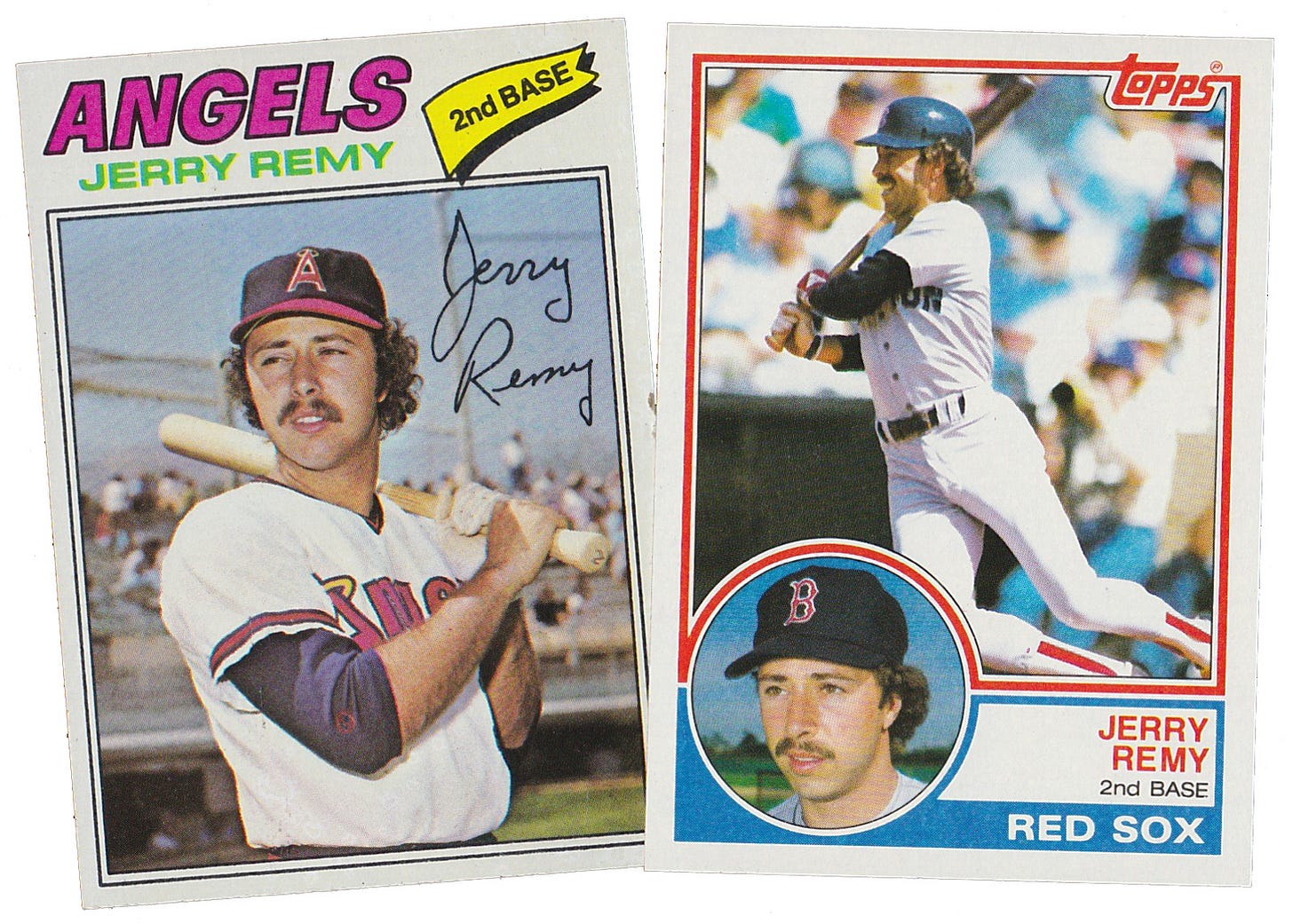

Jerry Remy (1952–2021)

Like Fosse, Remy was a beloved fixture in the broadcast booth for a team he also played for. Also like Fosse, he started his major-league career with another team. Unlike Fosse, however, Remy was a local boy, whose accent and demeanor brought an unmistakable local flavor to his team’s broadcasts.

Remy wasn’t from Boston, proper. He was born in Fall River and raised in Somerset, Massachusetts, in the southern part of the state along the Rhode Island border. With his thick regional accent and the moustache he wore throughout his adult life, the initial impression Remy gave off was that of a real-life Cliff Clavin, the mailman barfly from the Boston-based Cheers, a show that debuted while Remy was the starting second baseman for the local nine.

Remy wasn’t a big guy. Listed at a likely generous 5-foot-9 and 165 pounds, he was initially drafted in the 19th round in by the expansion Senators in 1970, but opted to go to Rhode Island’s Roger Williams University instead. That only lasted a few months as the Angels took him in the eighth round in the January second-phase draft in 1971. That time, Remy, still just 18, signed.

Remy had a couple of strong seasons in the minors in 1973 and 1974 and was the Angels’ Opening Day second baseman in 1975, making his major-league debut behind Nolan Ryan in a game the Halos won in a ninth-inning walk-off against the Royals. Remy didn’t hit much that year, or any of the others in his 10-year major-league career, but he was a slick fielder and a left-handed hitter with speed. In his first four seasons, he averaged 35 steals a year (at a 68 percent success rate) and hit a total of seven home runs. Over his final six seasons, he stole another 68 bases, but never hit another homer.

December 8, 1977 was surely one of the greatest days of Remy’s life. That was the day he was traded to his hometown Red Sox, straight up for righty Don Aase. Just as he had in Anaheim, Remy replaced Denny Doyle as the everyday second baseman. Remy was an All-Star for the only time in his first season with Boston, less because of any change in his performance than perhaps the slight bump he received from the change in ballparks and the lack of competition in the league. The Red Sox were a great team that year, but they collapsed late and suffered a brutal loss to the Yankees in the one-game playoff for the division title. Remy hit second for Boston in that game and doubled and scored in the eighth inning to help close Boston’s deficit. He then delivered a one-out single to put the potential winning run on base in the bottom of the ninth, but was stranded when Goose Gossage got Jim Rice and Carl Yastrzemski to pop out.

That was as close as Remy ever got to the postseason as a player, and his playing time ebbed and flowed in subsequent seasons, often interrupted by injuries. His already weak hitting declined precipitously as he entered his thirties, then his knees gave out. He only made it to May 18 in 1984 before missing the remainder of that season and all of the next with knee problems. The Sox released him in December 1985, and he retired during Spring Training 1986 at the age of 33 having not played in almost two years.

His broadcasting career started just a couple of years later, in 1988 with the New England Sports Network, then in just its fifth season on the air. As a color commentator, Rem Dawg became a New England icon and got to enjoy calling regular-season games for not one, not two, but four Red Sox championship teams.

Despite those highs, the last decade plus of Remy’s broadcasting career was marked by regular absences due both to his own health problems and a shocking family tragedy in 2013, when Remy’s oldest son, Jared, murdered his girlfriend and was sentenced to life in prison without parole. Jerry was first diagnosed with lung cancer in 2008 and battled multiple cases of pneumonia and his cancer for 13 years. He took his last leave of absence after calling the Sox’s win over the Tigers in Detroit on August 4. On October 5, he threw out the first pitch before the AL Wild Card Game against the Yankees. He died on October 30 at the age of 68.

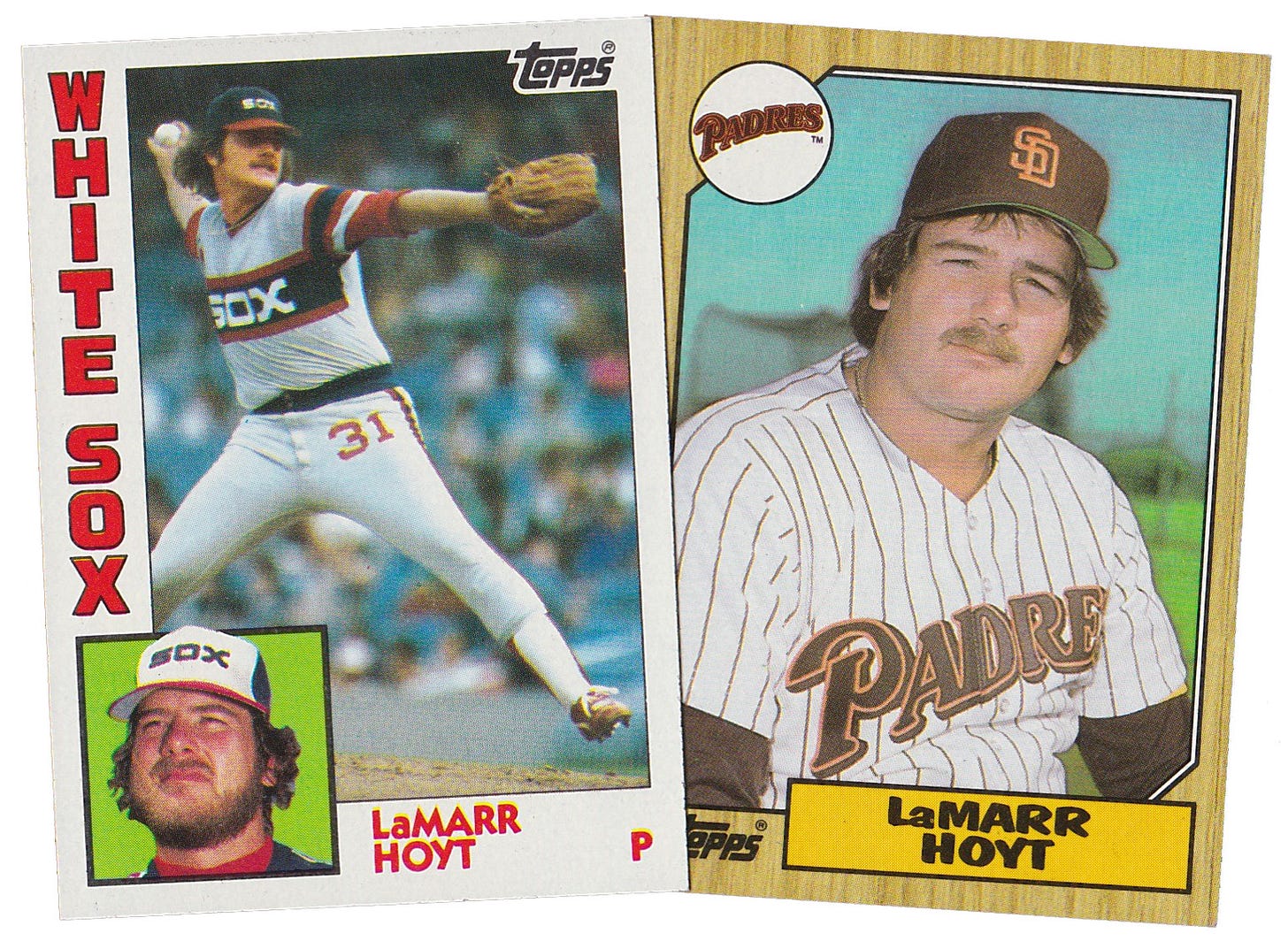

LaMarr Hoyt (1955–2021)

Dewey LaMarr Hoyt is best remembered for the 1983 Cy Young award that should have gone to Toronto’s Dave Stieb, but the more illustrative story that should be told about Hoyt’s career is about how it was cut short by medical negligence and a lack of compassion for his resulting drug addiction.

Drafted by the Yankees out of his South Carolina high school in 1973’s fifth round, Hoyt was included in the April 1977 trade that brought Bucky Dent to the Bronx from the Southside for Oscar Gamble. Hoyt made his major league debut with the White Sox in 1979, but didn’t stick in the majors until 1981, and didn’t become a fixture in the Chisox’s rotation until his age-27 season in 1982.

A big, shaggy, soft-bodied, soft-tossing right-hander, Hoyt was a control artist who succeeded by changing speeds and walking next to no one. From 1982 to 1985, the last of those seasons with San Diego, Hoyt averaged 237 innings and 18 wins a year with a 3.79 ERA (106 ERA+) and just 36 walks per season. His 3.7 percent walk rate over those four seasons was the lowest in baseball among pitchers with at least 600 innings pitched over that span. Drop that minimum as low as 25 total innings over those four years, and only submarining Royals fireman Dan Quisenberry was stingier with a walk.

Thanks to that low walk rate, and the pitchability that allowed him to survive throwing so many strikes, Hoyt led the majors in WHIP (1.02) and strikeout-to-walk ratio (4.77) in 1983, and led the AL in K/BB in 1984 (2.93). He also led the AL in wins in 1982 with 19 and the majors with 24 in 1983, which helped him best the 17-11 Stieb, who received no votes at all in the latter year’s Cy Young voting.

The big name in a six-player trade with the Padres in December 1984 that brought shortstop Ozzie Guillén to Chicago, Hoyt was an All-Star with the Padres in 1985. However, it was in that All-Star Game that Hoyt first felt the pain in his shoulder that would end his career and bring him to the lowest point in his life.

Despite Hoyt’s complaints about the pain in his shoulder, it wasn’t until he posted a 9.82 ERA in four August starts that the Padres shut him down, and they brought him back three weeks later to make five more starts (with admittedly excellent results) in September. Along the way, the shoulder just got worse, and Hoyt developed an addiction to painkillers.

In early 1986, Hoyt was arrested twice in a month’s span on drug charges, missed Spring Training while in rehab, then struggled upon his return, bouncing between the rotation and bullpen. That October, he was arrested again on drug charges, then suspended for the entire 1987 season by commissioner Peter Ueberroth. When that sentence was reduced by an arbitrator, the Padres released him. The White Sox gave him another chance, but he never got into another game. His shoulder was too far gone.

Scoping out his pitching shoulder, the Sox discovered what the Padres hadn’t even bothered to look for: Hoyt had torn three of the ligaments in his rotator cuff and had a 25 percent loss of bone in the ball-in-socket joint. The simultaneous dissolution of his career and his marriage, the constant pain in his shoulder, and a sleep disorder likely resulting from all of the above, caused Hoyt’s addiction to spiral. He needed medical and emotional help. What he got was fired from his job and thrown in jail.

Given how low he got, it’s remarkable and commendable that Hoyt eventually got clean, remarried, and found work as a salesman. It’s also all the more tragic that he went through all of that only to run right into a cancer diagnosis. He died November 29 at the age of 66.

Doug Jones (1957–2021)

When I hear (or use) the term “late bloomer” in reference to a baseball player, I can’t help but think of Doug Jones. Jones grew up in Lebanon, Indiana, and was drafted out of Central Arizona College by the Brewers in the third round of the 1978 draft. He made his professional debut as a 21-year-old in short-season ball in 1978, but advanced quickly and made his major-league debut for 1982’s eventual pennant winners. However, Jones made just four major-league appearances that year, lost most of 1983 to injury, struggled in 1984, and became a six-year minor-league free agent that October at the age of 27.

In Spring Training 1985, Jones was effectively a walk-on in Cleveland’s camp, but he came armed with a new changeup, and that pitch changed everything. Cleveland signed Jones to a minor-league deal and moved him into the bullpen. He was good in double-A in 1985, he was better in triple-A in 1986, and that September he was back in the majors. Jones made the major-league team out of camp in 1987, but spent May back in triple-A before returning for good in June and earning some save opportunities down the stretch.

Then, in 1988, his age-31 season, Doug Jones became a star. Installed as Cleveland’s closer, he racked up 37 saves, posting a 2.27 ERA (181 ERA+) and 4.50 strikeout-to-walk ratio in 83 1/3 innings over 51 games, including a then-record 15 consecutive saves (a record since utterly obliterated) from mid-May through early July. Jones was an All-Star that year and also received some MVP votes despite Cleveland’s sixth-place finish.

The next two years were more of the same, an average of 38 saves in 82 innings over 62 games with a 2.45 ERA (161 ERA+), 3.43 K/BB, and two more All-Star appearances. After a down year at 34, Cleveland figured they had gotten all they could out of Jones and non-tendered him. The Astros knew better, signing him to a three-year contract. In those three years, the last after a trade to the Phillies for fellow closer Mitch Williams, Jones saved another 89 games with a 2.83 ERA (132 ERA+), a 4.48 K/BB, and made two more All-Star teams.

Jones was 37 in the last of those seasons, but he was still far from done. He pitched another six years, with stints with the Orioles, Cubs, and A’s and reunions with Milwaukee and Cleveland, saved another 86 games, and posted a 124 ERA+ over that span, not retiring until after his age-43 season in 2000. Jones never made another All-Star team, but he got a few more down-ballot MVP votes with the Brewers in 1997 and reached the postseason with Cleveland in 1998 and the A’s in 2000. In his final appearance in the majors, he retired three of the four Yankees he faced in Game 4 of the 2000 Division Series. When he retired, his 303 saves ranked 12th all-time and, despite his late start, he ranked 21st all-time in games pitched (he is now 29th and 40th, respectively).

In retirement, Jones served as a pitching coach in the minors and for San Diego Christian College and started a Christian music record label called His Heart Music. He died on November 22 at the age of 64 from complications of COVID-19.

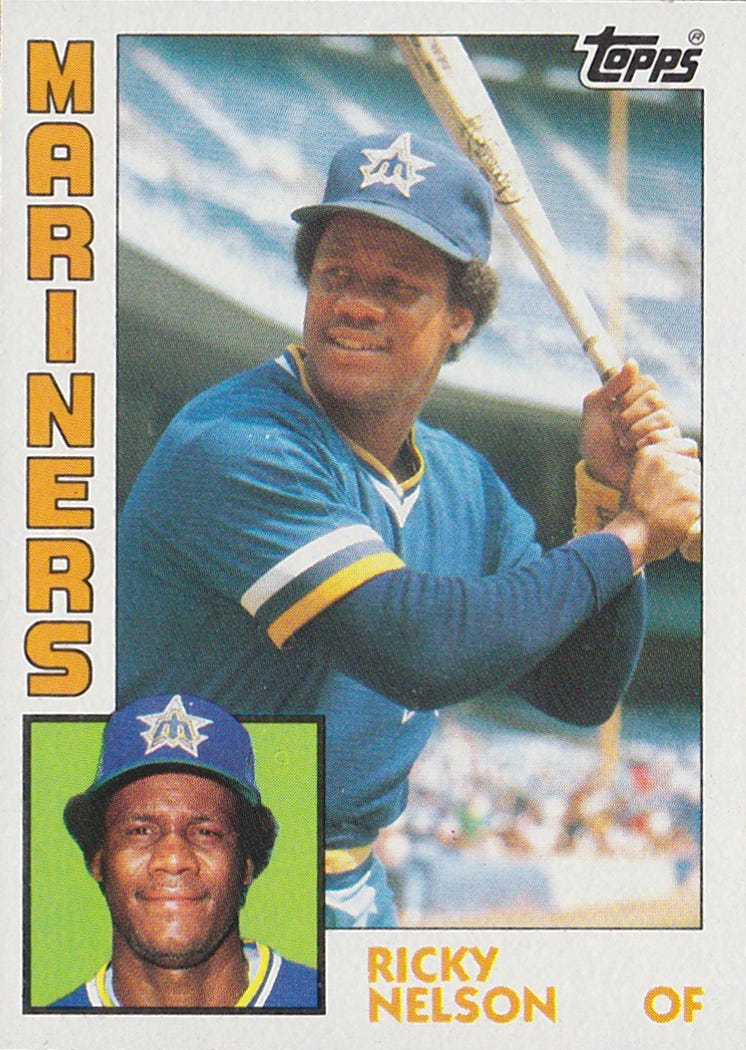

Ricky Nelson (1959–2021)

Ricky Nelson, who had the same birthday (19 years later) as the 1950s teen idol who shared his name, played 98 games for the 1983 Mariners, 91 of them in the outfield corners, but appeared in just 27 more major league games thereafter. A fourth-round draft pick out of Arizona State in 1981, Nelson wasn’t terribly memorable, or good, as a major-league player, but he got his name in the big book, and he deserves to be remembered.

Nelson grew up in Eloy, Arizona, about half-way between Phoenix and Tucson and was somehow both a sports star and a member of the varsity marching band in high school. Initially drafted out of Arizona State by the Angels in 1980, he stayed in school and won the College World Series with ASU’s talented 1981 team, then signed with the Mariners, who took him 20 rounds earlier than the Angels had the year before.

Nelson showed speed and some power in the minors and made his major league debut just nine days after his 24th birthday, but he failed to impress in his rookie season and never got another extended look. He passed through the Mets and Cleveland organizations in 1987, but was out of baseball before he turned 29.

In retirement, he finished his degree in exercise science and physical education at ASU, then worked as a probation officer in Maricopa County. He was also active in coaching local youth sports and helped establish the Arizona Diamondbacks’ training centers in 1998. In 2001, he managed the A’s Rookie League team in Arizona, and in 2013 he was inducted into the Santa Cruz Valley Union High School Hall of Fame. Nelson died of COVID-19 on November 19. He is survived by his wife, Carrie, six children, and several grandchildren.

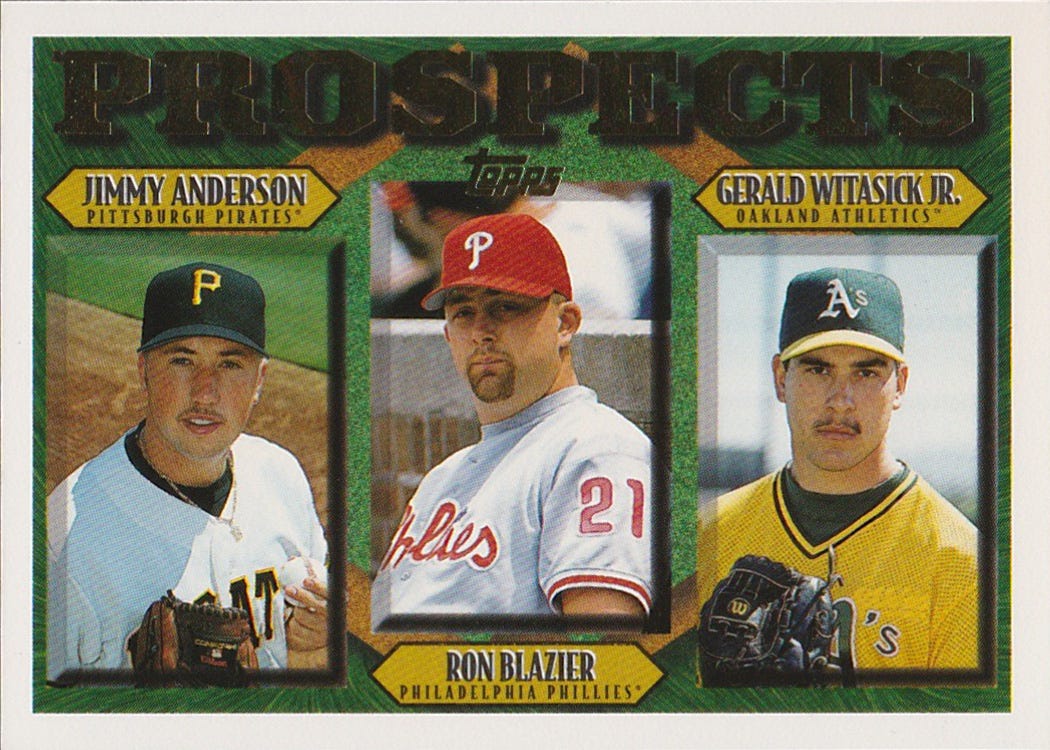

Ron Blazier (1971–2021)

Ron Blazier made 63 relief appearances for the Phillies over the 1996 and 1997 seasons. He wasn’t particularly good in those outings (5.38 ERA, 80 ERA+), and, I must admit, I have no memory of his brief career. That doesn’t mean it wasn’t worth remembering.

A native of Bellwood in central Pennsylvania, Blazier graduated from Bellwood Antis High School in 1989 and landed a minor-league deal with the Phillies via a tryout camp that summer. In 1992, at the age of 20, the big righty was a Sally League All-Star, posting a 2.65 ERA across 159 2/3 innings for the Spartanburg Phillies. He was moved to the bullpen in double-A in 1995, helping Reading to an Eastern League championship, and won the Phillies’ Paul Owens Award as organizational pitcher of the year. He spent some time as a closer in triple-A in 1996, and made his major-league debut on May 31, 1996. Blazier threw 5 2/3 scoreless innings across four appearances before allowing his first run in the majors on a solo homer by the Astros Derek Bell. Prior to that homer, Blazier struck out peak-era Jeff Bagwell on three pitches.

The ’96 and ’97 Phillies were last place teams, and, in July 1997, they sent Blazier, who had a mid-90s fastball and a hard curve, all the way down to High-A to learn a split-finger from none other than Bruce Sutter. Blazier was excellent upon his return (1.15 ERA with 16 strikeouts in 15 2/3 innings across 12 appearances). Unfortunately, Blazier missed all of 1998 due to Tommy John surgery and appeared in just 21 more professional games for the Orioles’ Sally League and double-A teams in 1999. Blazier was out of baseball at the age of 28. Nonetheless, in 2008, he was elected to the Blair County Sports Hall of Fame. In retirement, he worked construction, drove a forklift, and played softball on a local team, in addition to other hobbies. Blazier died unexpectedly at home at the age of 50 this on December 4. He is survived by three sons, ages 13 to 22, two brothers, and his mother.

Feedback

I want to hear from you. Got a question, a comment, a request? Reply to this issue. Want to interview me on your podcast, send me your book, bake me some cookies? Reply to this issue. I will respond, and if I find your question particularly interesting, I’ll feature it in a future issue.

You can also write me at cyclenewsletter[at]substack[dot]com, or @ me on twitter @CliffCorcoran.

Closing Credits

Is it too morbid to close out today’s issue with “Dead Man’s Party” by Oingo Boingo? Maybe, but that’s kind of where we are with today’s issue: “Going to a party where no one’s still alive.” Oingo Boingo, if you didn’t know, was the 1980s band of legendary film composer and frequent Tim Burton collaborator Danny Elfman (he’s the creepy redheaded lead singer in the video below). “Dead Man’s Party” was performed by the band onscreen in the 1986 Rodney Dangerfield comedy Back to School, for which Elfman also composed the score, just the third of his remarkable career, which is now in its fifth decade.

Once, again, The Cycle is going to take a few weeks off, but will return in late January to react to the BBWAA’s Hall of Fame voting and kick off its second season.

In the meantime: