The Cycle, Issue 3: Prospect Prospectus

Synthesizing the top-prospects lists, La Stella and Wainwright sign, New York pitching changes, Sara Goodrum’s promotion, and the Baseball Prospectus annual arrives

In this issue of The Cycle . . .

MLB Pipeline and The Athletic’s Keith Law released their top-100 prospects lists on Thursday. I combine their rankings with those of Baseball America and Baseball Prospectus to come up with a consensus top 10, rank the 30 teams according to their presence on the four lists, and dig around for other fun facts about the rankings.

Also:

Transaction Reactions: A Cable Car Named “Desire,” retaining Wainwright, remembering Tanaka, O’Day, Matz, Avila, and more

Personnel Department: Notable front-office and coaching hires and promotions

The Cycle Book Club: Baseball Prospectus 2021

Reader Survey

Closing Credits

Before we get started, word of mouth is very important to the growth and survival of The Cycle. Please spread the word, on social media and in person, and let people know how much you like The Cycle, and why!

If you have any trouble seeing all of this issue on your email, you can read the entire issue at cyclenewsletter.substack.com. If you are already reading it there because you haven’t subscribed yet, you can fix that by clicking here:

The Cycle will be moving to paid subscriptions soon, but this week’s issues have all been, and will remain, free, as will our next issue on Monday.

Promises, Promises: Sorting Through the Top 100 Prospects Lists

Lists are fun. Our culture loves ranking things, forcing ourselves, or others, to put two things of roughly equal quality in unequal places, then complaining bitterly that they’re in the wrong order, or that some other candidate not even being on the list renders the entire thing invalid.

Baseball is especially fond of lists. The Hall of Fame is a list without rankings, and I suspect many people would like it much more (or love to hate it more) if it was ranked. The standings are a ranked list, as are statistical leaderboards. The playoffs sort teams into a list that leaves both more room and no room for dispute. We love lists so much that many publications will create a hot list to rank the teams, which are already ranked by the standings, in a different order. When the offseason starts, we rank free agents. I will do my fair share of lists and rankings in this space, I’m sure. Yet, the listiest of baseball’s lists are the annual top-prospects lists.

There are now four major Top 100 Prospects lists that generate considerable buzz in the game. The originator is Baseball America’s Top 100, which was first compiled in 1990 (Braves lefty Steve Avery was ranked number-one). Baseball Prospectus started a top-40 list in 1999 (No. 1: Eric Chavez, 3B, A’s), but didn’t become real players in the prospect game until Kevin Goldstein moved over from BA and expanded BP’s coverage with a full Top 100 in 2007 (No. 1: Alex Gordon, 3B, Royals). The Baseball Prospectus list now goes to 101 and is authored by Jeffrey Paternostro, Jarrett Seidler, and Keanan Lamb. Keith Law didn’t rank prospects when he wrote for Baseball Prospectus in the late ’90s, but, after a stint in the Blue Jays’ front office, he started doing a list for ESPN in 2008 and has since taken that list to The Athletic. The most recent major addition to the annual prospect roundup is MLB.com’s MLB Pipeline, written by Jim Callis, also formerly of Baseball America, and Jonathan Mayo.

Baseball America and Baseball Prospectus released their 2021 lists last week. Law and Pipeline put theirs out on Thursday. They agree in some places, including in their top overall pick, but there are many more ways in which they differ. With all four lists in hand, I took some time Thursday night to pour over the rankings, dump them into a spreadsheet, and sort, tally, and weigh the rankings to produce both a consensus list and to grade each of the 30 teams in terms of their contributions to the lists. Here’s what I discovered:

All together, the four lists include 146 different players, just 65 of whom made all four lists, and 36 of whom made just one of the four lists, leaving 45 players who made multiple lists, but not all four. The highest ranked player to make just one list was Angels outfielder Jo Adell, who placed 13th on Baseball America’s list. Adell no longer qualifies as a rookie and was thus not considered for the other lists. Putting Adell aside, the highest ranking single-lister was Cleveland catcher Bo Naylor, whom Law ranked 42nd. The lowest-ranking player to make all four lists was Mets righty Matt Allan, whose averaged rank was 85.5. It seems everyone agrees he’s a prospect, but no one is all that enthusiastic about it. None of the four lists ranked him higher than 75th. The highest-ranking player who didn’t make all four lists is White Sox second baseman Nick Madrigal, whom Law did not rank. Madrigal was no lower than 40th on the other three lists, and his average score was 48.5.

A word about that average score: to calculate each player’s consensus ranking, I entered a “rank” of 102 every time a player failed to make a list (that’s one more than the lowest possible ranking on any of the lists, Baseball Prospectus’s 101). I then took the average of the four scores to come up with their consensus ranking.

That method produced this consensus list of the top 10 prospects in baseball entering the 2021 season:

Franco topped every list, a clean sweep. Rutschman ranked second on three of the four, with Law dissenting and listing him sixth. Kelenic ranked fourth on three of the lists and sixth on Baseball Prospectus’s, but he, Rutschman, and Franco were the only three players to rank in the top 10 on all four lists, so he took third in the aggregate rankings with ease.

With one exception, players 4 through 10 on the list above all ranked tenth or lower on two lists. The exception is Rodríguez, who was in the top 10 on three lists, but was ranked 24th by Law. That is the lowest ranking any of the 10 players above received on any of the lists.

One thing that’s striking about the top 10 above is that the Mariners, Padres, and Braves each have two players in the top 10, and both of the Braves’ players have not only reached the majors, but contributed to their playoff run last year. That got me wondering which teams had the greatest concentration of elite prospects, according to these lists, so I came up with a method to rank all 30 teams by their presence on the list.

Before I dive into the results, some fun facts and a note on method. Cleveland and the Rays had the most players to make any one of the four lists with nine each, but if you give each player only a quarter of a point for each list, thus requiring them to make all four lists to be “whole,” the Rays compile seven points to Cleveland’s 4.5. The Mariners had the most players to make all four lists: five. The Reds had the most prospects to make at least one list without having anyone make all four: six. Cincinnati also made the most lists without having a player that made all four (their quarter points add up to 2.5). Just two A’s prospects were ranked, both made just one list. The Nationals had just one player ranked on just one list.

To rank the teams, I subtracted every player’s consensus ranking from 102. Franco, for example would get 101 points (102 – 1), while Cleveland righty Daniel Espiño, who ranked 100th on the only list he made and thus had a consensus ranking of 101.5, got just a half a point. I then added up the player points for each team and sorted them by high score.

Bearing in mind that this is a measure only of the elite prospects in each farm system, not of the overall strength of the system, here are the results, in reverse order:

30. Washington Nationals (0.75) The Nationals had just one player receive a ranking, right-hander Cade Cavalli. Cavalli ranked 99th on MLB Pipeline’s list, giving the Nationals less than a point as an organization.

29. Oakland A’s (7.0) Arm injuries have undermined former sixth-overall draft pick A.J. Puk to such a degree that he made just one list, raking 84 on Law’s. The only other player in the organization to appear on a list is catcher Tyler Soderstrom, who ranked 92nd on Baseball America’s.

28. Milwaukee Brewers (18.5) The Brewers had just two ranked players. Shortstop Brice Turang made three lists, but outfielder Garrett Mitchell had a lower average rank thanks to placing 65th on MLB’s list.

27. Colorado Rockies (59.25) Outfielder Zac Veen, the ninth-overall pick last June, appeared on all four lists with an average rank of 58. Brendan Rodgers, who no longer qualifies as a rookie and therefore is ineligible for the majority of the prospect lists, was ranked only by BA. Lefty Ryan Rolison snuck onto the bottom of Law’s list at 84.

26. Houston Astros (61.0) Forrest Whitley, a consensus top-10 prospect two years ago, remains on all four lists with an average rank of 54.75. Righty Luis García and shortstop Jeremy Peña made just one list each.

25. Cincinnati Reds (65.0) Again, the Reds placed six players on one list or another, but none of them on all four. Leading that bunch is 2017’s second-overall draft pick, Hunter Greene, who is working his way back from April 2019 Tommy John surgery. Green averaged 75.75 while making two lists, getting all the way up to 28th on Law’s. Lefty Nick Lodolo led the Reds by making three lists, but his average rank is 79.5.

24. Philadelphia Phillies (72.25) The Phillies had just two prospects make the lists, but righty Spencer Howard, who made six major-league starts last year, averaged 49 and ranked as high as 27 on Baseball America’s list. Fellow righty Mick Abel made three lists, averaging 82.75.

23. Boston Red Sox (76.25) The Red Sox placed four prospects, but first baseman Triston Casas was the only one to make all four lists, averaging 65.75. Jeter Downs, part of the return for Mookie Betts, made three lists, averaging 69.5.

22. Chicago Cubs (86.75) The Cubs placed four players, two of them unanimous: lefty Brailyn Márquez (61.75), who got his first taste of the majors last year, and outfielder Brennen Davis (65.5).

21. Texas Rangers (88.25) The Rangers are the highest-ranking team not to have a player make all four lists. Third baseman Josh Jung, who was drafted eighth overall in 2019, made three lists, but not Law’s, while centerfielder Leody Taveras ranked as high as 26th on Baseball Prospectus’s list, but didn’t make BA’sor MLB Pipeline’s, averaging 68.5. Dane Dunning, who was acquired from the White Sox in the Lance Lynn trade, was ranked by BP and Pipeline, but not the other two, averaging 88.75.

20. Los Angeles Angels (108.25) Centerfielder Brandon Marsh tops the Angels’ quartet of prospects, averaging 42.75 as the only one of the four to make all four lists. Again, Jo Adell was ranked 13th by BA, but didn’t qualify for the other three due to the loss of his rookie (and thus prospect) status.

19. Los Angeles Dodgers (109.5) Righty Josiah Gray leads the Dodgers quintet with a 55.0 average across all four lists. Also making all four lists is Keibert Ruiz (66.0), who homered in his first major-league at-bat last August.

18. New York Yankees (120.75) The Yankees placed just three players, but righty Clarke Schmidt made all four lists, as did teenage enigma Jasson Dominguez, who has yet to play a professional game, won’t turn 18 for another week, but nonetheless averaged a 47.5 and topped out at 32nd on MLB Pipeline’s list.

17. New York Mets (123.25) Five prospects, two getting a single listing at 94th (third baseman Brett Baty by MLB, outfielder Pete Crow-Armstrong by Law), and three others unanimous: catcher Francisco Alvarez (49.75), shortstop Ronny Mauricio (51.5), and aforementioned righty Matt Allan (85.5, the lowest average rank of any player to make all four lists this year).

16. Cleveland (169.75) Cleveland placed a whopping nine players on these lists, but just two made all four (scrawny righty Triston “Dr. Sticks” McKenzie, 40.5, and third baseman Nolan Jones, 54.75). Meanwhile, shortstop Gabriel Arias’s lone ranking was 87th by Baseball Prospectus, shortstop Brayan Rocchio’s was 99th by Law, and the aforementioned righty Daniel Espiño’s was 100th by BP.

15. Arizona Diamondbacks (175.75) Baseball America’s willingness to rank players who have exhausted their rookie status rears its head again here. BA ranked Daulton Varsho 67th, but none of the others listed him at all. The other four Diamondbacks prospects made all four lists: outfielders Corbin Carroll (average rank: 36.5), Kristian Robinson (50), and Alek Thomas (70.75), and shortstop Gerald Perdomo (83.75).

14. Pittsburgh Pirates (187.5) There’s a big drop-off after Ke’Bryan Hayes here, but Hayes alone is worth 91 points as a consensus top-10 prospect. Shortstop Oneil Cruz was omitted from BP’s list due to the uncertainty about his legal jeopardy following a car accident in the Domincan Republic that left three dead. He may be absent from Law’s list for the same reason.

13. Minnesota Twins (195.0) Six players, two unanimous and very close in average score. Outfielder Alex Kirilloff, who made his major-league debut in the postseason last year, averaged 30.5, topping out at seventh on Law’s list, while shortstop Royce Lewis, the top pick overall pick in the 2017 draft, averaged 30.75, topping out at 17th on Pipeline’s list.

12. San Francisco Giants (211.25) Five players, three unanimous, and those three suggest a sort of prospect fatigue. Outfielder Heloit Ramos, who first cracked these lists in 2018, averaged 63.75. Catcher Joey Bart, the second overall pick in the 2018 draft and Buster Posey’s heir apparent, who made his major-league debut last year, averaged 33.5. Then there’s the new kid, 19-year-old shortstop Marco Luciano. He tore up the Arizona League as a 17-year-old in 2019 and averaged a 16.75 on the lists, peaking at eight on the Baseball Prospectus Top 101.

11. St. Louis Cardinals (218.25) Again five players, two appearing on just one list, including third baseman Jordan Walker at 92 on Baseball Prospectus. Three others are unanimous: lefty Matthew Liberatore (44.0), awkwardly named third baseman Nolan Gorman (43.0), and the jewel of the system, outfielder Dylan Carlson. Carlson, who impressed in last year’s postseason, cracked both BA and Law’s top 10 and averaged 11.75 to finish 11th overall in my aggregate rankings.

10. Kansas City Royals (231.25) The Royals quintet looks a lot like the cross-state Cardinals, at least in terms of the rankings. Two players scrape the bottom of a list or two (outfielder Erick Peña, 97th on Baseball Prospectus; righty Jackson Kowar, 95th on BA and BP), and three that rank on every list with impressive aggregate scores: lefty Daniel Lynch at 35.25, lefty Asa Lacy at 29.5, and shortstop Bobby Witt Jr., the second overall pick in 2019, who made the top 10 for both Baseball Prospectus and MLB Pipeline and averaged 14.75.

9. Chicago White Sox (241.25) We’regetting into the elite collections of talent now. The White Sox listed just four players, but three made all four lists, and second baseman Nick Madrigal missed just one (Law’s), raking 40th with BA and Pipeline and twelfth with BP. Below him is fireballing lefty Garret Crochet (65.25) and above him is Michael Kopech (28.25) and first baseman Andrew Vaughn, who was drafted one spot behind Witt and matches his average rank at 14.75.

8. Toronto Blue Jays (246.0) Given all the talent they have graduated in recent years, it’s very impressive that the Jays are still this high. Only two of their prospects are on all four lists, but both are elite, and they have seven players listed overall, including stocky catcher Alejandro Kirk (three lists, 91.25). Those elite prospects are 2020’s fifth-overall pick, shortstop (or, possibly, outfielder) Austin Martin, and righty Nate Pearson, who made four major league starts last year, was ranked fifth by Law, and averaged 16.0 between the four lists.

7. Miami Marlins (260.25) Four of the five Marlins prospects to be ranked made all four lists, but all eyes are on righty Sixto Sánchez, who was sixth on BA’s list, fourth on BP’s and ranked 12th overall in the aggregate rankings with a 12.50 average.

6. Atlanta Braves (272.25) The Braves ranked seven players, five of whom failed to make all four lists, but Pache and Anderson both made the aggregate top 10 and were thus worth 182.5 points all by themselves.

5. Baltimore Orioles (277.75) The Orioles had better be up here given the quality of team they’ve been putting on the field at the major-league level in recent years. The big payoff for all that losing was taking Rutschman first overall in 2019. He ranked second on every list but Law’s, where he was sixth. There’s a good drop off from there to righty Grayson Rodríguez, who averaged 33.5, then another to lefty DJ Hall at 57.75. Ryan Mountcastle, who raked in his major-league debut last year, didn’t make Law’s list, but ranked 28th on BP’s. His average is 67.50.

4. San Diego Padres (302.0) Like the Braves, the Padres ranked seven players and placed two, lefty MacKenzie Gore and shortstop CJ Abrams, in the aggregate top 10. That’s 187.5 points just from those two alone. Catcher Luis Campusano averaged 45.0. Outfielder Robert Hassell is at 67.75. That’s four players to make all four lists. Their bottom three are all at the major-league level already: Ryan Weathers, who debuted in last year’s postseason (91.25 on two lists), Adrian Morejon (76th on BA) and Korean import Ha-Seong Kim, who was 78th on BA but may not have been considered for the other lists.

3. Seattle Mariners (381.25) The Mariners are one of just two teams to have five prospects make all four lists. Those five are shortstop Jazz Chisholm (56.75), righties Emerson Hancock (48.0) and Logan Gilber (38.25), and their two top-10 outfield prospects, Julio Rodríguez and Jarred Kelenic.

2. Detroit Tigers (383.0) The Tigers are another team that had better be here given the misery of their major-league team. They had five prospects earn a ranking, and all five made all four lists. They are lefty Tarik Skubal (41.25), righty Matt Manning (30.5), outfielder Riley Green (26.25), 2018’s top overall draft pick, righty Casey Mize (19.25), and 2020’s top overall pick, and 2021’s seventh-overall prospect on the aggregate list, first baseman Spencer Torkelson (9.75).

1. Tampa Bay Rays (401.0) Having the consensus number-one prospect sure helps, but the Rays would rank fourth on this list even without Wander Franco. They placed a whopping nine players on these lists, four of whom have appeared in the majors: lefty Shane McClanahan (another player who made his major-league debut in the 2020 postseason, 91.5), lefty Brendan McKay (who has settled in as a full-time pitcher, 77.25), Randy Arozarena (who hit .358/.429/.790 with 10 home runs in 91 postesason plate appearances and is amazingly still rookie-eligible), and new addition Luis Patiño, acquired from the Padres in the Blake Snell trade. Among their four players to make all four lists are second baseman Vidal Bruján (52.0), Arozarena (29.0 with a high of 17th at Baseball America), Patiño (20.75, with a high of 16th from Law), and, of course, after all that, we wander right back to Franco.

Wander Franco, who was also the consensus number-one prospect last year, won’t turn 20 until March 1 and hasn’t played an official game above High-A. Still, it would not be the least bit surprising to see the switch-hitting shortstop, who has an 80-grade hit tool, per Baseball America, in the majors at some point this season.

Transaction Reactions

Giants sign 2B Tommy La Stella ($19.5M/3yrs)

That $19.5 million, as reported by Susan Slusser of the San Francisco Chronicle, is not bad money for a 32-year-old who doesn’t play his position well and has never made more than 360 plate appearances in a single major-league season.

La Stella made his name as a bench player and pinch-hitting specialist with the Cubs from 2015 to 2018. In November 2018, the Angels acquired him for minor-league lefty Conor Lillis-White, who has yet to throw a competitive pitch in the Cubs’ organization due to injury and the pandemic. Given the starting second-base job in Anaheim, La Stella raked, made the All-Star team, then got hurt and missed both the All-Star Game and most of the remainder of the 2019 season.

Healthy again last year, he was even better at the plate, prompting the A’s to acquire him as a deadline rental in exchange for infielder Franklin Barreto, who had once been the big prospect in the Josh Donaldson trade. La Stella just kept hitting, right into the postseason, and the Giants clearly hope he’ll continue doing so on the other side of the Bay. Over the last two years, which add up to one full season for La Stella, he has hit .289/.356/.471 (122 OPS+) with 21 home runs and just 40 strikeouts in 549 plate appearances.

The snag is that La Stella is a poor fielder at second base, a position the Giants already had manned by another productive late bloomer, Donovan Solano. Solano is a more talented fielder, and thus will likely move into a utility role. A right-handed hitter, Solano could spell the lefty La Stella or left-hitting shortstop Brandon Crawford against southpaws, and will surely get some extra playing time filling in for injuries around the Giants’ aging infield. When this deal becomes official, La Stella, who turns 32 on Sunday, will become the youngest infielder on San Francisco’s 40-man roster.

Cardinals re-sign Adam Wainwright ($8M/1yr)

This contract took longer than expected, but it was expected. Wainwright has spent his entire 15-year career with the Cardinals. He’s third in team history in wins (167, behind Hall of Famers Bob Gibson and Jesse Haines), second in strikeouts (1,830, way behind Gibson’s 3,117), fourth in starts (adding Bob Forsch to Gibson and Haines), sixth in innings pitched, and seventh in games pitched.

He will turn 40 in August, but he proved he could still endure a full, healthy season in 2019, then proved he could still be an above-average starter in 2020, posting a 137 ERA+ across 10 starts with a 3.60 strikeout-to-walk ratio, his best in half a decade. Despite a poor outing in the 2020 Wild Card Series, Wainwright still has that big-game moxie, posting a 1.62 ERA in 16 2/3 postseason innings in 2019 to go with his 2.89 career mark in 109 postseason frames. Now, the big question is if the Cardinals will bring back the only active player who has been with St. Louis longer, Wainwright’s 38-year-old catcher, Yadier Molina.

Yankees sign RHP Darren O’Day ($2.45M/1yr + $1.4M player option/$3.15M club option)

O’Day has long been underrated because of his sidearm delivery and soft stuff. Indeed, he hasn’t broken 90 miles per hour with a pitch since 2017, according to Brooks Baseball, which adjusts for ballpark variations in radar readings. So, you might be surprised to learn that, among active pitchers with at least 500 innings pitched, he ranks third in ERA+ at 172. The only pitchers ahead of him on that list are Craig Kimbrel (188) and Aroldis Chapman (183), and O’Day has thrown more innings in the majors than either of them (albeit just eight more than Kimbrel). Leave off his rookie year with the Angels, and O’Day’s ERA+ jumps to 183 in 533 1/3 innings, which matches Chapman’s career mark in just 14 fewer frames.

Over the past three seasons, O’Day has posted a 194 ERA+ and struck out 11.9 men per nine innings with a 5.50 strikeout-to-walk ratio. So how did the Yankees get him so inexpensively? Well, for one thing, he’s 38 (and will turn 39 before the end of the World Series). For another, he has thrown just 41 2/3 innings over those last three seasons. O’Day missed time with hamstring injuries in 2016 and 2018, and a different part of 2016 and most of 2019 with forearm injuries. He was healthy last year, but only asked to make 19 appearances in the shortened season. The concern here, then, is not performance but health.

That might explain the curious option situation on this contract. According to Joel Sherman, O’Day will make $1.75 million this season, then have a player option for 2022 worth $1.4 million with a $700,000 buyout. If he declines that, likely because he stayed healthy and increased his value, the Yankees will have a $3.15 million club option on him for 2022. All of which means he’ll either be a Yankee or retired in 2022. For O’Day and the Yankees both to decline their options, both player and team would have to stubbornly place his value for the 2022 season in that narrow window between $1.4 million and $3.15 million. As for the $2.45 million “total value” of his contract listed above, that’s the value (2021 salary plus 2022 buyout) that’s relevant for the competitive-balance tax calculations, which reportedly leaves the Yankees with a little less than $6 million left to spend before triggering the tax.

RHP Masahiro Tanaka signs two-year contract with Rakuten Eagles

I mentioned this possibility on Monday. Having found Major League Baseball’s free agent market wanting, Tanaka is returning to Japan. That should be an embarrassment for MLB and the owners, but I can’t imagine Tanaka is terribly upset about leaving a country that completely botched the pandemic response to return to his home country, and his former team, to do what he loves to do and make more money than he could have here. Tanaka, who signed a seven-year, $155 million contract with the Yankees in late January of 2014, posted a 114 ERA+ in 1,054 1/3 major league innings comprising 173 starts and one relief appearance. He was an All-Star as a rookie in 2014 and again in 2019, and finished fifth in the Rookie of the Year voting in the former season, and seventh in the Cy Young voting in 2016. The 2016 season was, indeed, his best in the States, as he posted career-bests in ERA+ (140), innings (199 2/3), starts (31), and, for what it’s worth, wins, going 14-4.

Tanaka arrived in U.S., at the age of 25, facing sky-high expectations and completely lived up to them in his first three months in the majors. Over his first 16 starts, he went 11-3 with a 2.10 ERA, 0.95 WHIP, and a 7.05 strikeout-to-walk ratio, completing three of those starts, including a shutout of the Mets at Citi Field, and averaging more than seven innings per outing. He then had a couple of rough starts to start July and was diagnosed with a partially torn ulnar collateral ligament, which limited him to just two more apperances in the second half of the season. Tanaka never needed Tommy John surgery, and proved to be a wizard at altering his approach to accommodate whatever was or wasn’t working on a given day, but he was never that dominant pitcher again.

Except, perhaps, in the postseason. In total, Tanaka posted a 3.33 ERA in ten postseason starts, but the first eight of those starts yielded a 1.76 ERA. His best October came in 2017, when he allowed a total of just two runs in three starts across 20 innings, including tossing seven scoreless against both Cleveland in Game 3 of the Division Series and the Astros in Game 5 of the American League Championship Series, both Yankee wins. Tanaka, ultimately, wasn’t able to live up to the hype, but he did enough to earn the respect of the Yankees, their fans, and fans of Major League Baseball in general. I wish him nothing but the best back home.

Blue Jays acquire LHP Steven Matz from Mets for RHPs Sean Reid-Foley, Yennsy Díaz, and Josh Winckowski

When the Mets won the pennant in 2015 with a young rotation of stud Matt Harvey, sophomore Jacob deGrom, and rookies Noah Syndergaard and Steven Matz, baseball was abuzz about that quartet’s potential. Perhaps you’ve heard, it didn’t work out. Yes, deGrom has emerged as the best pitcher in baseball, winning consecutive Cy Young awards in 2018 and ’19, but Harvey almost immediately turned into a pumpkin, Syndergaard has struggled to stay healthy, and Matz has thus far proven to be the least accomplished of the bunch. Matz got some Rookie of the Year votes in 2016, but has never qualified for an ERA title, was bounced to the bullpen late last year, and leaves town with a career ERA+ of 91.

It’s a shame to see a kid from Long Island named “Matz” traded away from the team he grew up rooting for, but he is entering his walk year and age-30 season and has very little left to offer the Mets. The Blue Jays, meanwhile, are throwing a lot at the wall this offseason and will see what sticks once Spring Training and the regular season begin. One encouraging sign: Matz had career highs in strikeout rate and strikeout-to-walk ratio last year. Of course, the latter was still just 3.60, they came in just 30 2/3 innings, and he allowed a whopping, almost unbelievable, 14 home runs in those 30 2/3 innings. Still, the Jays must believe Matz’s potential is still there if they’re willing to give up three warm bodies for him.

As for those warm bodies, Reid-Foley, one of just two major leaguers born in Guam (but raised in Florida), is a 25-year-old righty with control problems to the tune of six walks per nine innings over 71 2/3 major-league frames. He’s raw material for the underside of the major-league bullpen. Yennsy Díaz is a 24-year-old Dominican righty who missed last year’s abbreviated season with a right latissimus dorsi strain. He’s a middling minor league starter whose only action above Double-A was facing seven major-league batters in 2019 and walking four of them. Winckowski, 22, is another undistinguished right-handed minor league starter who did not pitch last year.

Mets sign LHP Aaron Loup ($3M/1yr)

After losing most of 2019 to an elbow injury, Loup, a stocky, sidearming southpaw, surprised last year with a strong season for the Rays that recalled his younger days in Toronto (see his only regular-issue Topps card above). That performance helped Tampa Bay reach the World Series. As fairly generic lefty relievers in their thirties will do, however, he’s on to the next one on a one-year deal with the Mets, who already had an impressive collection of righties in the bullpen, but were in need of a lefty complement. SNY’s Andy Martino reports that the deal will be worth “approximately $3 million.”

Nationals sign C Alex Avila to a one-year deal

Avila suffered four concussions in a 13-month span from August 2013 to the final day of the 2014 season. The last three came in relative quick succession and called into question the wisdom of Avila continuing to catch. He has kept his head clear and his gear on since then, however, and a half-season of hot hitting on his return to the Tigers in early 2017 helped sustain the idea of Avila as a productive backstop. I say “idea,” because he has hit .184/.238/.349 (79 OPS+) in 497 plate appearances over the last three seasons. In Washington, the 34-year-old (as of today, Happy Birthday, Alex!) will replace Kurt Suzuki and give Dave Martinez a left-handed backup to righty Yan Gomes.

This signing, reported by Ken Rosenthal, reunites Avila with three of the Nationals’ top four starters. He caught Max Scherzer with the Tigers, Jon Lester with the Cubs, and Patrick Corbin with the Diamondbacks. Scherzer and Corbin will likely be glad to see him, Scherzer having posted a 3.27 ERA in 107 games with Avila behind the plate and Corbin a 3.34 ERA in 14 such games. Lester . . . not so much. He only threw to Avila twice while with the Cubs and posted an 11.74 ERA in those games.

Cubs sign RHP Kohl Stewart to major-league contract

Stewart was the fourth-overall pick in the 2013 draft, selected out of a Houston-area high school by the Twins. He made it to the majors in 2018, but in 62 major-league innings, across six starts and 11 relief appearances in 2018 and ’19, Stewart struck out just 34 men against 26 walks. He was lousy at Triple-A, as well, in 2019, prompting Minnesota to outright him off the roster. Stewart refused the assignment, was released, and landed with the Orioles, who kept him at their alternate training site last year. I don’t know if the Cubs saw him there and liked something, or if they’re just desperate for starting options after losing John Lester, José Quintana, and Tyler Chatwood to free agency, but they’ve given Stewart, who is now 26, a big-league contract and a spot on their 40-man for the coming season. Don’t expect much.

Personnel Department

Mets hire Zack Scott as acting general manager

Team president Sandy Alderson is the final word on player personnel decisions in the Mets’ front office, but Scott will assist him as the interim replacement for the disgraced Jared Porter, with a chance to get that “acting” label removed. Scott, a 43-year-old white man, spent the last 17 years with the Red Sox, the last two as an assistant general manager in charge of analytics and scouting. The Mets originally hired him last month as one of Porter’s assistants.

Brewers promote Sara Goodrum to Coordinator–Hitting Development Initiatives

I wouldn’t normally take the time to discuss a minor league coaching move (Goodrum’s wordy title amounts to “minor league hitting coordinator”), but I’m very excited about the inroads women are making into major- and minor-league coaching staffs, and want to highlight and celebrate those whenever possible. The Brewers originally hired Goodrum in 2017 to work in their Sports Science and Integrative Sports Performance lab (another mouthful). This promotion puts her in charge of hitting instruction for all of the Brewers’ minor leaguers.

Goodrum played softball at the University of Oregon and has a masters in exercise and sports science from the University of Utah. Jake McKinely, the Brewers’ director of development initiatives (they’re killing me with these titles) called Goodrum, “an elite technician of hitting [with] a great feel for people and . . . an awesome human being.”

Goodrum is the first woman to lead the hitting instruction for an organization’s entire minor league system. Three other women currently hold jobs as hitting coaches in the affiliated minor leagues, Rachel Folden (Cubs, Arizona League), Rachel Balkovec (Yankees, Gulf Coast League), and Bianca Smith (Red Sox), the last of whom is the first black female coach in affiliated baseball. The Giants’ Alyssa Nakken remains the only woman on a major league coaching staff, but that increasingly seems likely to change sooner rather than later.

Brewers hire Junior Spivey as Coordinator of Baseball Diversity Initiatives

Spivey’s position is a new one the Brewers created to provide support to minority players. It is believed to be the first of its kind in the majors, and is a welcome acknowledgement of the additional difficulties that minority players face in the majors. For anyone skeptical about the need for such a position, six former major-leaguers—Doug Glanville, LaTroy Hawkins, Torii Hunter, Jimmy Rollins, Ryan Howard, and Dontrelle Willis—who discussed those difficulties in a roundtable with The Athletic’s Ken Rosenthal last June. Spivey, who is black, spent five years in the majors from 2001 to 2005, including parts of two seasons with the Brewers, and remained active in the minors until 2009.

The Cycle Book Club: Baseball Prospectus 2021

The Cycle will include reviews of notable baseball books (and movies, baseball card sets, etc.) from time to time, but they will be somewhat sporadic, as I’m not a terribly fast reader, at least when it comes to books. The Baseball Prospectus annual, however, is a book with a limited shelf life. My copy arrived in the mail on Wednesday, but the review can’t wait for me to read all of its 1,500-plus player comments and nearly 40 essays, so I’m going to give you my first impressions and let annual’s reputation do the rest.

I can’t be impartial about the BP annual. I still feel somewhat invested in its continued success, even though I haven’t had anything to do with the book* in nearly a decade. In 2006, before I quit my day job as a book editor, I signed BP to a three-year contract with Plume and edited the 2007 and ’08 editions. I also contributed chapters to five editions (2006 and 2009–12).

*I still draw an occasional check from Baseball Prospectus when they publish one of my movie reviews as part of their Great BP Baseball Movie Guide.

That copy line on the front, “The Essential Guide to the [####] Season”? That’s mine. Those who have a long row of BPs on their shelf, as I do, will notice that line first appeared on the first Plume edition in 2007. I’m tickled every year when I see it’s still on the cover. My subtitle for The Cycle “Your companion to Major League Baseball’s seasons,” is an intentional echo of that. I love that idea of providing baseball fans with something they can read throughout the season to enrich the experience of watching the games.

The Baseball Prospectus annual is a great guide (or companion) to the baseball season. It is the product of some of the game’s most insightful observers, savviest analysts, and best writers dumping their brains out into a massive book that you can browse at your leisure. Look up your favorite player or the new acquisition you’ve never heard of. In almost every case, that player has a comment in this book. Every team gets its own chapter, with an essay followed by approximately forty to fifty player comments. I refer to it constantly in my work to make sure I haven’t missed anything about a given player or to learn more about a young player I haven’t had a chance to see. I absolutely used both the 2021 edition and past editions in writing this issue of The Cycle.

The book is also a massive undertaking. Again, I edited this beast twice. It’s a job I don’t want back. For most books, nine months elapse from the author’s delivery of the manuscript to the book going on sale in stores. That time is spent editing for content, copyediting, creating the page design, setting the text, proofreading, correcting, designing the cover, standing up marketing and publicity, etc. The BP annual, an oversized book of roughly 600 pages dense with text and statistics (so, more like a 1,000-page book, if not more), is created from scratch, from the first letter typed on a blank page to the finished copy in the readers’ hands, in about three months.

It has to be. In non-pandemic times, November, December, and January are the only months of the year without major-league players in uniform. As a result, the book is famously error-prone. In the first edition I edited, which just happened to be the one that hit TheNew York Times’bestseller list, the Adrián Beltré comment was accidentally deleted during layout. By the time we noticed, it was too late to fix it (Beltré is still in the index, but he’s not in the book). The very first, self-published edition, in 1996 (the only one I don’t own, because it was made on a photocopier and purchased by fewer than 200 people), had 27 team chapters. It left out the St. Louis Cardinals. (The Cardinals were restored to the online edition, available here). I haven’t detected anything that egregious in this year’s edition, but you don’t have to read far to find a typo or a missing word. Knowing the near impossibility of getting this book finished at all, I find that relatively easy to forgive.

Raising the degree of difficulty even further, Baseball Prospectus’s senior staff bought the brand’s independence in late 2018, and BP has been self-publishing the book ever since. This is the third edition published by BP’s company, DIY Baseball, and there are still some amateurish tells in the page design. As someone who moonlights as a proofreader, I may be overly sensitive to these things, but word spacing as large as a half centimeter, of which there is at least one example in this edition, is likely obvious to non-editors, as well. Ditto something like pages 167–8, where, amidst the Blue Jays’ pitcher comments, the bottom half of one page is empty despite the fact that the top two comments on the next page would fit there comfortably. Elsewhere, the statistical introduction introduces two new pitching metrics included in the players’ statistical tables, fastball percentage and whiff rate, abbreviating them as FB% and WHF. An inch and a half lower on the page is an example of the pitcher stat tables that appear throughout the book; it abbreviates the new stats as FA% and Whiff%.

I have a couple other minor complaints, which, again, may be primarily a result of my overfamiliarity with the book. BP has made a variety of small but noticeable improvements over the years. I love the graphic snapshots for each team. I was happy to see individual bylines for the team essays and player comments appear for the first time in 2014. The number of contributors has ballooned, from 20 in my first year of involvement (a group that included the book’s editors), to 61 this year, not counting seven non-writing editors. That brings a diversity of voices to the book that was missing in the old days.

Those are all positives, but one change I noticed this year concerns the Line Outs. In 2006, my good friend Steven Goldman, who edited the book from 2005 to 2011, added blocks of quick-hit, single-sentence player comments to the end of each team section. It was a way to cram another twenty-odd marginal players into each team chapter without having to devote space to a full statistical table for each. The Line Outs survived until last year. This year, they’re gone . . . or are they?

I didn’t notice their absence upon my initial survey of the book, but I did notice several regular player comments that were just one sentence long. My initial impression was that all of these one-sentence comments were an unfortunate side effect of the book being rushed, but I’m now wondering if they are actually Line Outs that were given full stat tables. If so, that’s technically an upgrade (same comment, more stats), but I can’t find any mention in the book of that being the case. As a result, less-familiar readers may think those comments are a cheat, when they’re actually getting more (if, indeed, they are).

Also, when I edited the book, all 30 teams were placed in the book alphabetically, and players were placed in the chapter of the team with which they finished the previous season. That made it easy to find what you were looking for by just flipping through. George Springer? H for Houston. S for Springer. Done. This year’s book has the teams arranged by division, but not by league, so you get the teams in the NL East, then AL East (which isn’t alphabetical), then the Centrals, then the Wests, and the players are listed with their new teams, but only if they changed teams before publication. George Springer? Well, he’s on the Blue Jays. Oh, but he signed too late for the book to know that, so back to the Astros. Where are the Astros? They’re in the AL West, so . . . argh. At least there’s an index.

I find the practice of putting players with their new teams particularly frustrating. I understand the impulse, the book feels more up-to-date, but it locks it in time in an incomplete offseason and leads to situations such as that on page 20. That’s in the Braves chapter and features the player comments of Charlie Morton, a new Brave in 2021, and Darren O’Day, who just signed with the Yankees on Wednesday, too late for the book to know. Morton and O’Day were never teammates on the Braves, but they’re together in the Braves chapter.

Fortunately, what matters most is the content, and, in quantity and quality, it is well worth the investment*. In addition to the usual team essays and player comments, statistical tables and snapshots, manager stats, and the Top 101 Prospects list, with unique comments for each prospect, this year’s edition has essays from Rob Mains on 2020’s abnormalities, Marc Normandin on the coming labor battle, Russell A. Carleton on WAR’s shortcomings, Eric Nusbaum on the human cost of MLB’s purge of the minor leagues, Steven Goldman on, well, death (which visited all too often in and out of baseball in 2020), and Adam Sobsey on . . . the experience of watching baseball in 2020, I think. I haven’t had a chance to read that one yet.

*Speaking of which, if you order directly from BP before February 28 and use the code PLAYB21, you’ll get 30 percent off and free shipping.

It also contains a new section with comments and statistics for select players from Nippon Professional Baseball, the Korea Baseball Organization, and Taiwan’s Chinese Professional Baseball League. The focus in those sections is on the Western players playing in those leagues, but there are a good number of native players, as well, whose names are printed according to the local custom (that’s family name first in Korea and Taiwan) and accompanied by their names in Japanese, Korean, or Chinese characters. That’s a tremendous addition, and no easy task. I applaud BP and eagerly anticipate perusing those sections. I hope you will, as well.

Reader Survey

In order to serve you better, I would like to know a little more about you. This is optional, of course, but, if you don’t mind, please reply to this issue with:

your favorite team (or teams, or if you are a general-interest baseball fan)

your general location (as many of the following as you feel comfortable sharing: city, state, province, country for those outside the U.S. and Canada)

your birth year (because it doesn’t change, unlike your age)

The idea here is to know whom I’m writing for, what teams you want to read about, and when and where you’ll receive the newsletter. I can’t promise I’ll write more about the Mariners if you tell me you’re a Mariners fan, but if there’s a large Mariners contingent among the readership, I will likely lower my threshold for including Mariners items and dive deeper into the ones I include.

Closing Credits

I do have one actual credit to offer today, not for work done on this issue, but for a gesture done for The Cycle, in general. Craig Calcaterra, formerly of NBC Sports’ Hardball talk and now the proprietor of substack’s leading sports newsletter, the baseball-focused, but also very wide-ranging (beyond both baseball and sports), Cup of Coffee, took the time to make an elaborate pitch for this newsletter in his. That was above and beyond the call of duty, led quite a number of you here, and is very much appreciated. I’ve thanked him directly, but I wanted to include a note here, as well. If you have time and money for two baseball newsletters in your life, Craig and I approach things very differently, and I believe Cup of Coffee and The Cycle are complimentary, rather than competitive. Craig agrees, of course, because he’s a mensch.

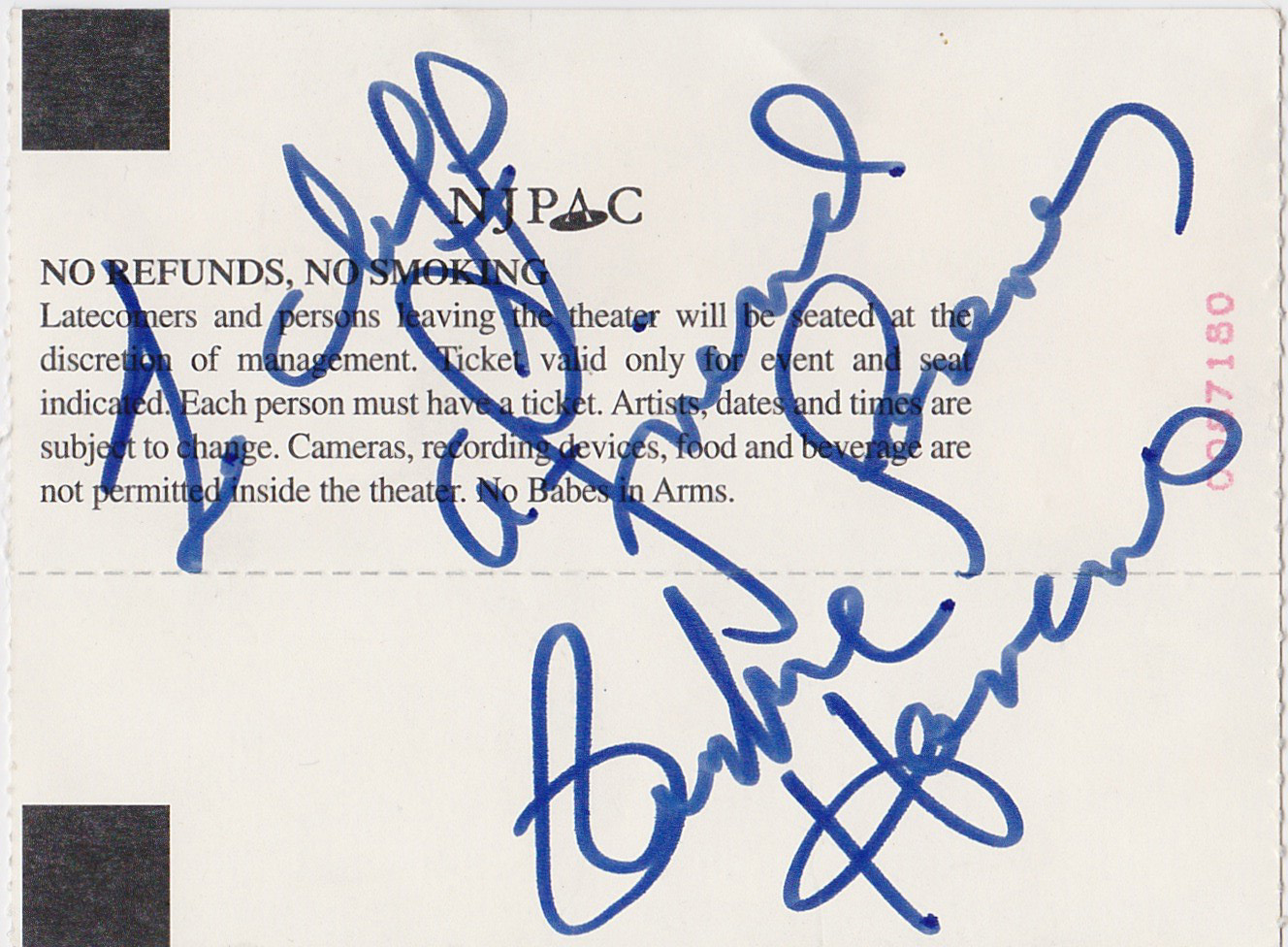

On to the song. I’ve loved Richie Havens’ voice and unique, rhythmic guitar playing ever since I first saw the original Woodstock film on PBS as an adolescent. In 1999, one day after my 23rd birthday, I got to meet him. My girlfriend (now wife), myself, and several friends went to that year’s New Jersey Arts & Music Festival on the grounds of Newark’s Performing Arts Center (NJPAC). It was a Sunday afternoon. They got the tickets to see the Violent Femmes, but I was also excited about Havens, Los Lobos, and Koko Taylor. John Sebastian was also performing, as were others I’ve since forgotten (the Chieftains? probably the Chieftains). After Havens performed on the main stage, looking just a little older than he had at Woodstock and dressed quite similarly, I noticed him off to the side, near a chain-link gate that led back to his bus or trailer or whatever green-room sort of situation was provided, talking to just a couple of fans. At my girlfriend’s suggestion, I went over and had a chance to shake his hand, compliment him, and get my ticket signed. He wrote “To cliff, a friend forever, Richie Havens.” For years I thought I’d lost it, but, just last year, I went to clean out an old box of memories, and there it was. Havens died in 2013, but forever ain’t over.

“There’s a Hole in the Future” opens side two of Havens’ sixth record, 1970’s Stonehenge (yes, he put out a record called “Stonehenge”; this was 14 years before Spinal Tap). Havens was best known for his covers, but “There’s a Hole in the Future” is an original composition. It has a bit of a Jackson 5 strut in the bass, no drums, but a lot of percussion (including Havens’ guitar), and some strings buried in the mix. I choose it for today not because, like the careers of too many prospects, it is over too quickly, but because the concluding refrain has just the right combination of hope and cynicism for the future for someone dreaming on a highly-regarded baseball prospect:

There’s a hole that’s waiting in the future, Mona

It could already be filled when we get there.

The Cycle will return on Monday with another free issue. In the meantime, please help spread the word!