The Cycle, Issue 125: The Best of Everything

Previewing the season by picking the Best of Everything in each league, plus the Nats' cherry blossom uniforms, new MLB and MiLB rules for 2022, what you need to know, and more . . .

In this issue of The Cycle . . .

What You Need to Know: New MLB rules adopted, this year’s minor-league rule experiments, plus umpire announcements, sticky stuff checks, humidors, PitchCom, and good news on the Apple TV+ games.

Rooting for Laundry: The City Connect program returns in D.C.

The Best of Everything: Picking the best teams and players in various categories in each league heading into the 2022 season

Feedback

Closing Credits

What You Need to Know

Ohtani Rule and Other 2022 Rule Adjustments Are Official

Last week, I wrote about the rule adjustments on which that Major League Baseball and the Players Association had come to terms. Those rules, including loosening of roster restrictions through May 1, the return of the automatic runner in extra innings for 2022 only, and the new “Ohtani Rule” governing the designated hitter, are now official and were announced by MLB and the MLBPA on Thursday. To review (with some added detail):

Roster Rules: Through May 1, to compensate for the abbreviated Spring Training, active rosters will expand to 28 players (29 for double-headers), with no restrictions on the number of pitchers on the roster, and optional assignments will not count toward the new CBA’s seasonal maximum of five. Starting on May 2, the roster rules will revert to those initially intended to take effect in 2020 but thus far put on hold due to the pandemic and lockout. Those include a maximum of 26 players (27 for doubleheaders) with a maximum of 13 pitchers, a minimum injured-list stay for pitchers and two-way players of 15 days, and a minimum optional or outright assignment for pitchers and two-way players of 10 days. Rosters will return to a maximum of 28 in September, as they did last year. Because of the limited expansion of rosters in September, September will no longer be omitted from service time when calculating rookie eligibility, as was the case last year.

Automatic Runner: Same as last year, every inning after the ninth will begin with a runner on second base.

Ohtani Rule: Starting pitchers who bat for themselves, with their team forgoing the designated hitter, will be treated as two separate players in terms of substitutions. Thus, if such a two-way player is removed from the game as a pitcher, they can continue to hit in the DH spot and, if they are removed from the game as a hitter, they can continue to pitch. Teams can thus leave a pitcher at DH for a full game, even if he is replaced on the mound, and can reclaim the DH spot with a pinch-hitter. However, the split treatment is not transferable to a two-way player pitching in relief, who would be treated as a single player as under the previous rules. This rule will remain in place for the duration of the current Collective Bargaining Agreement as a feature of the universal designated hitter.

Also:

Starting this season, umpires will make announcements over the ballpark public address system explaining replay review decisions. Such announcements have long been part of the replay review process in the NFL, NBA, and NHL.

Umpires will be checking pitchers more thoroughly for foreign substances between innings as MLB believes, based on spin-rate data, that pitchers were finding ways to continue using grip-enhancing substances late last season. Specifically, the umps will be checking the pitchers’ hands, using the admittedly sound logic that, for the sticky stuff to get on the ball, it would have to get on their hands as well. These enhanced checks have already begun in exhibitions games.

All thirty teams will store their game balls in humidors this season, regulating the condition of the ball throughout the league. Ten teams had already been using them, most famously the Rockies, but also the Diamondbacks, Astros, Blue Jays, Cardinals, Mariners, Marlins, Mets, Rangers, and Red Sox. Teams like the Rockies and Diamondbacks used the humidors to combat the thin, dry air at their ballparks, but teams such as the Mariners and Marlins derived the opposite benefit, keeping the balls slightly drier than they might otherwise have been in their damp, seaside climates. It will be interesting to see if the use of the humidor helps improve batting performances in similar cities known for their pitching-friendly ballparks, such as San Diego, San Francisco, and Tampa Bay.

Pitchers and catchers have been experimenting with PitchCom this spring, a device which allows catchers to communicate pitches wirelessly to pitchers. The device is part of a series of proposals from the league aimed at reducing sign stealing, and could also speed up games as it would eliminate the need for visible signs, multiple signs, and changing signs. The league has also proposed limiting the degree to which players can consult and coaches can alter scouting reports during games.

Good news on the streaming front: the MLB games on Apple TV+ are free to all, no subscription required. Well, the first 12 weeks of games are free. That’s 24 games in all, two per night, every Friday night from April 8 to June 24. As for the rest of the season, it’s unclear. Apple’s press release announcing the schedule for those 24 games said only that “‘Friday Night Baseball’ games will be available to anyone with internet access across devices where Apple TV+ can be found.” However, when Apple tweeted about the announcement, it said “free for a limited time.” I don’t know if that means only those 24 games will be free, or if the archived versions of the games will move behind the paywall after a certain amount of time, but this is at least good news for the time being and I tentatively retract some of my cynicism about this deal.

This Year’s Minor-League Rule Experiments

MLB announced this year’s slate of experimental minor-league rules back on March 14, and they are more focused than in years past. All of them related to issues that were reportedly discussed during the labor negotiations and foreshadow rules we are likely to see implemented in the major leagues as early as next year. Very quickly, they concern the pitch clock, limits on shifting, larger bases, and the automatic ball-strike system (ABS).

This year, all full-season affiliated minor leagues will use a pitch clock allotting pitchers 14 seconds between pitches with the bases empty and 18 second with runners on (19 seconds with runners on in Triple-A), and hitters must be ready to hit with nine seconds remaining on the timer.

Also, all pitchers in those leagues will be limited to two pickoff attempts or step-offs per plate appearance. MLB claims that rule and the pitch clock reduced the time of game by more than 20 minutes in the Low-A West and Arizona Fall Leagues last year. The pitch clock now seems inevitable, but I don’t like the limit on pickoffs. Yes, it absolutely would speed up the game, but it would also allow baserunners to take huge leads after that second pickoff throw. And, yes, I do love the stolen base, but I love the cat-and-mouse of it. Giving the runner such a big advantage throws that balance out of whack. That said, it is likely to result in many more back-picks from catchers, and if the ABS eliminates catcher framing from the game, we’re likely to see an increased emphasis on catcher arm strength from the combination of the two rules.

ABS is only being implemented at two levels, but one of those is Triple-A. It won’t be used all season at every Triple-A stadium, but it will be used all year at the home park of the Charlotte Knights, the White Sox’s Triple-A team, and throughout the Triple-A West starting on May 17. ABS will call all the pitches in those locations, but Low-A Southeast, which used ABS last year, will introduce a challenge system for select games, in which each team has three challenges per game to appeal to ABS for a pitch ruling, with with only unsuccessful appeals counting toward that three-challenge total (similar to MLB’s replay system). That challenge system had previously been used in the Atlantic League and Arizona Fall League. As someone who thinks instant replay has improved the game, I look forward to ABS reaching the major-league level. But about those checked swings . . .

Conversely, I loathe the idea of limiting shifting, for reasons I’ve detailed here and elsewhere numerous times. Sadly, it seems likely to happen next year. This year, it’ll happen in Double-A, High-A, and Low-A via a rule requiring four fielders in the infield and two on either side of second base when a pitch is delivered. To me, the shift makes the game more interesting and more entertaining, it introduces more variety from pitch-to-pitch and batter-to-batter, as well as the potential for some genuinely creative defensive alignments. Meanwhile, efforts to curb it seem to stem from a backward, reactive conservatism that misunderstands both the effects of the shift and the likely effects of limiting it, the latter of which will likely only benefit the sort of three-true-outcome lefty hitters those old-school types also grouse about. So, humbug on this one, to say the least.

Finally, and least significantly, all minor league levels will use larger bases, going from 15-inch bases to 18-inch bases (remember that home plate is 17 inches across, so 18 inches is hardly out of proportion). The idea there is to limit collisions around the bases by giving runners and fielders more real estate to work with around the bag. The bases will also be made from a material less likely to become slippery in wet conditions. That the larger bases will also reduce the space between first and second and second and third by 4 1/2 inches, potentially benefiting the running game, is a side effect MLB embraces. I’m fine with all of that. Injuries are the worst, and stolen bases are awesome, so an effort to reduce the former that could increase incentives for the latter is just peachy with me.

Not included in that March 14 announcement is the fact that the minor leagues are also moving second base, correcting a geometric irregularity with the placement of that base that dates back to 1887. As Jayson Stark illustrated over at The Athletic, if you trace the diamond of the field down the foul lines and from the back of first and third base toward second, you find that your lines intersect not at the rear of second base, but in the middle of it, as plainly illustrated in the field diagram in the MLB rulebook:

That is to say, second base is not in line with first and third, so this year the minor leagues are going to fix it so that it is. As a result, the distance from first to second and second to third is going to decrease even more, by a whopping 13 1/2 inches when you combine the relocation of the base with the fact that all three bases will be larger. Again per Stark, that reduces that distance from 88 feet, 1 1/2 inches (it was never 90 feet) to 87 feet even. As long as the resulting spike in stolen bases doesn’t throw things completely out of whack in the minors this year, we’re likely to see that change in the majors in the coming years, as well.

Rooting For Laundry

Nike’s City Connect uniform program, which will introduce home-city-themed alternate uniforms for all 30 teams by the end of 2023, kicked off its second wave on Tuesday with the reveal of the Washington Nationals new cherry-blossom-themed alternates. The Nationals are the first of seven teams who will unveil their City Connect uniforms this year, following the Red Sox, Marlins, White Sox, Cubs, Diamondbacks, Giants, and Dodgers, who introduced their Nike-mandated alternates last year. You can read my full breakdown and ranking of last year’s City Connect unforms—including when they were introduced and how often they were worn—in Issue 118. The other teams that will join the City Connect program this season are the Astros (April 20), Royals (April 30), Rockies (June 4), Angels (June 11), Brewers (June 24), and Padres (July 8). (And, yes, that’s only 14 of 30 total teams in two years of what we’ve been told is a three-year program, so it seems something is off about the pace of the unveiling or the information we have about the duration of the program, but I’m just going off the information that has been reported, primarily by Chris Creamer of the outstanding SportsLogos.net).

The Nationals City Connect uniforms, which were revealed in a cross-sport tie-in with the NBA’s Washington Wizard’s similarly-themed City Edition unis, celebrate Washington, DC’s annual cherry blossom blooms. I’ve been to DC when the cherry blossoms are in bloom, and they are magnificent and could have made for a lovey pink-on-white uniform echoing the appearance of the blossoms against the monuments on the National Mall. Unfortunately, Nike opted against such an elegant look for both the Nationals and the Wizards.

The Wizards at the very least got something colorful, using pink as the base color:

The Nationals somehow wound up with uniforms that are a dark gray:

These uniforms combine so many things that I dislike, none of which are cherry blossoms or the color pink. Rather they are the use of a dark, charcoal gray, particularly on a cap, sublimated patterns, floral patterns, the “WSN” abbreviation for Washington, beveling shading in a uniform typeface, and altering the colors of an official flag.

The only other dark gray caps I can think of in the major leagues were the gray home caps the Blue Jays introduced in 2004. Those might have been the worst caps in MLB history. They were so bad they lasted just two years, though that uniform design (also bad) lasted eight. Another example of how bad dark gray can look on a baseball field: the 2016–19 Diamondbacks road uniforms.

Sublimated patterns are a bad idea because they’re impossible to see from any reasonable distance. They’re also tacky. These jerseys look stone washed from a distance and like grandma’s couch up close. That latter is why I dislike floral patterns, in general. I don’t mind flowers as an accent. The branch of blossoms on the chest? That works. The sublimated floral pattern, however? Looks like a hotel bedspread.

As for abbreviating Washington, this is a tricky one that has long been a bit of a pet peeve of mine. In fact, I wrote about it in my review of last year’s dreadful All-Star uniforms in Issue 68. There just is no good three-letter abbreviation for “Washington.” Last year’s All-Star jerseys used “WAS.” These City Connect jerseys, and last year’s July 4 caps, use “WSH.” I suppose WSH is preferable to WAS, because, as I wrote last year, there is no S sound in “Washington,” the H is crucial. Before the Post Office adopted two-letter abbreviations for every state in 1963, the state of Washington was abbreviated “Wash.” I’ve long believed that the best three-letter abbreviation for Washington, DC, is WDC. That DC gives the abbreviation more specificity in a way that would have worked very nicely on a City Connect jersey. Not that it was necessary to use an abbreviation at all.

The beveling, which sullies the otherwise sharp current Angels’ and Astros caps, just adds more unnecessary detail that doesn’t show up from a distance. It’s clutter and doesn’t even look good up close in this set.

Finally, flag colors are often chosen for a very specific reason, and many flags around the world differ from others only by their use of color. Washington, DC, has a very distinctive flag, based on the Washington family’s coat of arms, which dates back to the 14th century. That symbol has been red on white for more than six centuries. Rendering it pink on gray on these uniforms turns it into something other than the district flag. That said, the flag is the least of my complaints about these uniforms, and I do love this hoodie.

Looking at my rankings of last year’s seven City Connect uniforms, I would probably rank these fifth, below the White Sox’s Southside unis but ahead of the Red Sox’s Boston Marathon look, Arizona’s unintentionally yellow Serpientes uniforms, and the Dodgers’ all-blue, which remains by far the worst uniform in a program that has introduced more bad than good thus far.

The Best of Everything

In 2018, in an attempt to carve out a season-preview niche for myself over at The Athletic, I introduced my Best of Everything series, endeavoring to identify the best lineup, rotation, bullpen, hitter, fielder, pitcher, etc. in each league heading into the season. I brough the Best of Everything to The Cycle last year, and I’m happy to bring it back again this year (the fourth instalment in five years, skipping 2020 for the usual reasons). This is pretty self-explanatory and, at least for me, quite a lot of fun. With Opening Day now less than a week away, these are the teams and players I’m most excited to see take the field and why.

Best Lineup

American League: Blue Jays

The Astros led the American League in runs last year, but they have since lost Carlos Correa to free agency and are handing his job to a rookie, Jeremy Peña, who has played just 30 games above High-A. Behind the Astros were the Rays and Jays, separated by 11 runs. Both seem likely to experience some regression this year, while the Red Sox added Trevor Story and the White Sox just added AJ Pollock.

Those five teams are the contenders here. My pick is the Blue Jays because I see more upside in their lineup. No, I don’t think that even a rejuvenated Matt Chapman is going to fully replace what Marcus Semien did at the plate last year, and, despite his youth, Vladimir Guerrero Jr. is likely to regress some from his near-MVP breakout. Still, I think the upside in the Jays’ lineup is higher than for those other teams.

The only player over 30 in the Jays’ lineup, or on their bench, is George Springer, who is just 32 and could contribute significantly more after appearing in just 78 games last year. Guerrero is just 23, so he could repeat or even improve on last year. Bo Bichette is just 24. Alejandro Kirk is 23. Cavan Biggio is 27 and due for a rebound from a poor, injury-plagued 2021. Catcher Danny Jansen finished the 2021 season with a breakout at the plate and has hit well this spring, and the team could add one of the top hitting prospects in baseball, Gabriel Moreno, into the catching/DH mix, as the season progresses.

Here’s the Jays’ projected Opening Day lineup along with each player’s OPS+ from the last two seasons:

National League: Dodgers

The Dodgers showed considerable faith in both Gavin Lux and Cody Bellinger when they traded AJ Pollock to the White Sox for closer Craig Kimbrel on Friday. However, when the worst hitters in your lineup, even after trading corner outfielder with a 135 OPS+ over the last two seasons, are a 26-year-old with an MVP award on his mantle and a 24-year-old former first-round pick and top-10 prospect who is coming off a big September surge, you know you could spare the bat to benefit the bullpen.

The Dodgers led the NL in runs scored last year. Relative to Opening Day a year ago, their big changes—beyond the addition of the universal designated hitter, which, along with the Pollock trade, will allow Lux and Chris Taylor to play more regularly—are that they effectively replaced Corey Seager and Pollock with Freddie Freeman and Trea Turner. Which is to say, they got better.

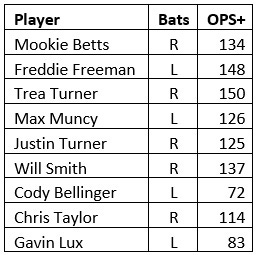

Here’s their projected Opening Day lineup (again with each players’ OPS+ from the last two seasons):

Major Leagues: Dodgers

Best Team Defense

American League: Rays

The strength of the Rays defense is their outfield, with Kevin Kiermaier in center flanked by Randy Arozarena and a likely platoon of Manuel Margot and Brett Phillips, but they are also strong up the middle, with catcher Mike Zunino and shortstop Wander Franco also both well above average. They’ll miss Joey Wendle in the field this year, but Taylor Walls could be an outstanding defensive replacement at second and third, and while his play doesn’t grade out terribly well, Ji-Man Choi is surprisingly great at the doing the splits at first base.

National League: Cardinals

It’s very rare to find a team that is above average defensively at every position on the field, but the Cardinals are that. Centerfielder Harrison Bader and left fielder Tyler O’Neill are elite. Corner infielders Nolan Arenado and Paul Goldschmidt are, as well, though some might argue that both have fallen off a little with age, ditto 38-year-old catcher Yadier Molina. Playing in the shadow of those five, the double-play combination doesn’t get the respect it deserves, but second baseman Tommy Edman is outstanding, and both Paul DeJong and Edmundo Sosa are at or even above his level. That just leaves right fielder Dylan Carlson, a 23-year-old who played a lot of center field in the minors. He’s still above average, but on a team that won six Gold Gloves in 2021, his above-average play in right makes that the Cardinals’ weakest position, defensively.

Major Leagues: Cardinals

Best Rotation

American League: Blue Jays

With the return of Justin Verlander from Tommy John surgery, the Astros finished a close second here, but Lance McCullers Jr. is opening the year on the injured list, and we saw how quickly the Astros’ rotation could think out, despite its depth, in the wake of McCullers’s injury in last year’s postseason. Heading into the season, I have more confidence in the Blue Jays’ intended quintet of José Berríos, Kevin Gausman, sophomore Alek Manoah, and lefties Hyun Jin Ryu and Yusei Kikuchi, both in terms of durability and effectiveness.

National League: Brewers

I almost went with the Mets here, then Jacob deGrom was diagnosed with a stress reaction in his right scapula on Friday, which will cost him all of April, and likely at least part of May. On paper, the Mets’ rotation of deGrom, Max Scherzer, Chris Bassitt, Taijuan Walker, and Carlos Carrasco is indeed the best in the majors, but age (Walker is the only one of the five under 33) and injury concerns, somehow exacerbated by this being the Mets, diminish the likelihood of that quintet fulfilling its potential.

The Brewers, in contrast, don’t have a single starter over 29 in their rotation, and another highly regarded young arm on deck in top prospect Aaron Ashby. Corbin Burnes, the defending NL Cy Young award winner, has a 185 ERA+ over the last two seasons and put up some goofy peripherals last year. Brandon Woodruff, who finished fifth in the Cy Young voting last year, has a 161 ERA+ over the last two years. Freddy Peralta, the youngest of the group at 26, posted a 152 ERA+ in his first full season in the starting rotation last year and has Cy Young-quality stuff. Lefty Eric Lauer and groundballer Adrian Houser round out the group, Houser with a career ERA+ of 117, and Lauer likely closer to a league-average arm, but in a rotation with three Cy Young contenders and an above-average groundballer, a league-average lefty is a more-than-adequate fifth starter, and there are many who believe Lauer is better than that.

Major Leagues: Brewers

Best Bullpen

American League: Yankees

I had the White Sox as the best bullpen in the majors until the team traded Craig Kimbrel to the Dodgers and it was announced that lefty fireballer Garrett Crochet will likely need Tommy John surgery. Without those two high-leverage arms, not to mention Michael Kopech shifting into the rotation, the Sox have fallen back into the pack, where the Yankees and Angels rival them for this title. Ultimately, I went with the Yankees, in part because I have a very high opinion of multi-inning set-up men Chad Green and Jonathan Loáisiga, and because I think they have more depth than the Sox and Halos, with righties Clay Holmes and Michael King and lefties Lucas Luetge, Joely Rodríguez, and Wandy Peralta.

National League: Braves

We’ve seen how impressive the Braves’ high-leverage lefties—Tyler Matzek, A.J. Minter, and Will Smith—can be over the last couple of postseasons, and this offseason the team got them a bit more right-handed help in closer Kenley Jansen, who frees the homer-prone Smith from the ninth inning, and multi-inning man Collin McHugh, who was outstanding for the Rays last year after sitting out 2020. Mix in incumbent righty Luke Jackson, and that’s six pitchers, three from each side, that manager Brian Snitker will trust in high-leverage situations, and the Braves have many options to choose from, from both sides of the hill, to round out the last few spots.

Major Leagues: Braves

Best Manager

American League: Kevin Cash, Rays

What is the strange alchemy that leads to that Rays devil magic (Devil Rays’ magic?). Some of it is outstanding team building by the front office. Some of it is perception, a failure to appreciate just how good the Rays’ players actually are. And the rest is the brilliance of manager Kevin Cash and his coaching staff. Cash has led the Rays the postseason in the last three seasons, the division title in the last two (winning Manager of the Year both years), and the World Series in 2020. In 2021, Tampa Bay set a franchise record with 100 wins, doing so in a division in which the top four teams all won more than 90 games. All of that by a team that is hardly plug-and-play. Cash has juggled platoons, openers, matchups, multi-position players, all without losing the clubhouse or the division. In 2021, he used 158 distinct batting orders in 162 games. In 2020 he repeated a batting order only once in 60 games. In 2019, he used “only” 152 batting orders. All three of those teams exceeded expectations and went to the playoffs.

National League: Dave Roberts

I happen to think Bob Melvin is one of the best managers in baseball, period, and could wind up in the Hall of Fame if he can lead the Padres to that elusive championship before the end of his tenure in San Diego. However, Melvin’s stuff has yet to work in the playoffs, and Dave Roberts’s record, no matter how good his rosters have been, is jaw-dropping. Roberts’s Dodgers teams don’t just win, they dominate. He has a .622 winning percentage in his six years at the helm in L.A., that’s a 101-win pace sustained over six years. Roberts’s Dodgers have won 106 games in each of the last two full major-league seasons, and in the last five years they have won three pennants and a World Series. One World Series may not seem like a lot, but Roberts is one of only three active managers to have won a World Series with his current team without also having spent a year suspended from the game for cheating. It’s just Roberts, Brian Snitker, and Dave Martinez. Yes, Roberts manages a team that, year in and year out, has the highest payroll and arguably the best roster on paper, but it’s no small feat to have that team play up to its potential every single year.

Major Leagues: Cash

Best Hitter

American League: Mike Trout, Angels

Last year, with Mike Trout on the injured list for most of the year with a calf strain that just wouldn’t heal, Vladimir Guerrero Jr. was very obviously the best hitter in the league. Here’s what Vladito did last year:

.311/.401/.601 (169 OPS+)

Here’s what Mike Trout has done over the last five years despite a series of injuries that have eaten away at his playing time:

.303/.442/.630 (187 OPS+)

When he got hurt last year, Trout had a 195 OPS+. Injuries and a decline in the field and on the bases may have eaten away at Trout’s status as the best player in the game, but there is no argument to be made that he is not still the game’s best hitter.

National League: Juan Soto, Nationals

Here’s what Soto has done in the last two years, his age-21 and -22 seasons:

.322/.471/.572 (185 OPS+)

That’s darn close to Trout’s numbers at a more advanced age (though also over a much larger sample). However, Soto has also benefited from leading the majors in intentional walks each of the last two seasons, suggesting his on-base percentages are at least slightly inflated due to the weakness of the lineup around him. Of course, he’s so good that maybe if he saw more strikes he’d hit for more power and it would all either come out in the wash or he’d be even more valuable. This year, he’ll have Nelson Cruz hitting behind him, so I hope we get to find out how good the 23-year-old Soto can be when pitchers actually have to pitch to him. For now, though, Trout remains the best in the business.

Major Leagues: Trout

Best Fielder

American League: Michael A. Taylor, CF, Royals

September 2020 hip surgery had a deleterious effect on Matt Chapman on both sides of the ball last year. As a result, new Tigers shortstop Javier Báez is now the must-see fielder in the American League, but the best by the numbers appears to be Royals center fielder Michael A. Taylor. Taylor has to be that good, because he can’t hit a lick. He’s a career .239/.293/.386 (79 OPS+) hitter in more than 2,000 plate appearances, and he was worse than that last year. Despite that, he started 135 games in center for the Royals. Why? Because his glove is so good that he was still between two and three wins above replacement level (depending on your source) despite being close to an automatic out at the plate. He is the Jeff Mathis of center fielders, but with a defensive value that is easier to see.

National League: Harrison Bader, CF, Cardinals

Bader had an uncharacteristically subpar year in the field in 2020, which is why he was not my pick in this spot a year ago, but he rebounded fully in 2021 according to the top defensive metrics, which means he has been an elite fielder the last three full seasons, which is more than I can say about Taylor, who didn’t get much playing time with the Nats in 2019 and 2020. That consistency (yes, I’m willing to fully disregard the short-season fielding-stat result from 2020) is what puts Bader over the top as the best fielder in baseball in my book.

Major Leagues: Bader

Best Baserunner

American League: Whit Merrifield, Royals

With a hat tip (or helmet flip) to José Ramírez, who is regularly among the very best in the majors in the various baserunning metrics, this goes to Merrifield this year, as he led the AL with 40 stolen bases in a mere 44 attempts (that’s a 91 percent success rate) and was at or near the top of the league in the broader, advanced baserunning statistics that factor in taking extra bases via other methods.

National League: Starling Marte, Mets

Only Marte consistently out-did Merrifield on the bases last year. Marte led the majors with 47 steals in 52 attempts (a 90 percent success rate), and also led in FanGraphs’ baserunning metric and in Bill James’ bases above average, both by a considerable distance.

Major Leagues: Marte

Best Pitcher

American League: Gerrit Cole, RHP, Yankees

As I explained last year, there’s a dearth of elite starting pitching in the American League these days. This offseason, the AL lost two more Cy Young contenders to the NL with Carlos Rodón’s defection to the Giants and the A’s trade of Chris Bassitt (top 10 in the voting each of the last two years) to the Mets. Cole hasn’t been quite as sharp with the Yankees as he was with the Astros, and it remains to be seen just how much the crack down on sticky stuff will affect him (again, the league is planning stricter inspections this year), but no AL pitcher has been as consistently excellent year in and year out over the last four years as Cole. Cole has finished in the top five in the Cy Young voting in all four of those seasons, striking out more than 35 percent of the batters he has faced with a 5.52 strikeout-to-walk ratio and a 153 ERA+ over that span.

National League: Jacob deGrom, RHP, Mets

He may be hurt with increasing regularity. He may miss two months, half the season, or more, but when Jacob deGrom is on the mound, he is so much better than every other pitcher in baseball that I cannot list anyone else here. Last year, deGrom made just 15 starts and was still a four-plus win player who finished in the top-10 in the Cy Young voting. Over the last four seasons, he has a 205 ERA+, 6.50 strikeout-to-walk ratio, 0.88 WHIP, has struck out just shy of 35 percent of the batters he has faced, held his opponents to a .189 average, and in those 15 starts last year he was, somehow, impossibly, far better than any of that. He has added velocity to his fastball in each of his last five seasons, his age-29 to -33 seasons. He appeared to be on the verge of breaking the game last year, posting a 1.08 ERA (373 ERA+) and 13.27 K/BB in those 15 starts while striking out more than 45 percent of the batters he faced. Instead, he appears to have broken himself, but if there’s any hope of him throwing even close to 100 innings this year, and I believe there is, he will remain the Best Pitcher in Baseball.

Major Leagues: deGrom

Best Reliever

American League: Liam Hendriks, RHP, White Sox

Over the last three seasons, this late-blooming, foul-mouthed Australian has posted a 2.08 ERA (207 ERA+), 8.84 K/BB, 0.83 WHIP, struck out just shy of 40 percent of the batters he has faced, and led all AL relievers with 6.2 wins added per win probability added.

National League: Josh Hader, RHP, Brewers

After finishing seventh in the NL Cy Young voting in 2018, Hader saw his home runs allowed spike in 2019 and his walk rate spike in 2020. In 2021, however, he brough both down and had arguably his most dominant season. He isn’t a multi-inning fireman anymore. He has settled into a traditional one-inning closer’s role, but in that role in 2021 he posted a 1.23 ERA (348 ERA+), 0.84 WHIP, and allowed just three home runs in 58 2/3 innings. Over the last four seasons, he has posted a 2.30 ERA (187 ERA+), 0.83 WHIP, and struck out more than 46 percent of the batters he has faced. Over the last three years, he has trailed only Cole and deGrom among all pitchers in WPA with 8.5 wins added. Go back four years and only Max Scherzer climbs ahead of him.

Despite all of that, I’m putting Hendriks ahead of Hader for best reliever in the majors in part due to workload, but also due to control of the strike zone. Hendriks has walked just 10 men (two in intentional) in 96 1/3 innings over the last two years and threw nearly as many innings in 2021 as Hader did in 2020 and ’21 combined.

Major Leagues: Hendriks

Best Player

American League: Shohei Ohtani, RHP/DH, Angels

Shohei Ohtani isn’t the best player in baseball at any single thing, but he is among the best at everything he does, and he does everything. Even fielding. No, he doesn’t play the infield or outfield, but he has demonstrated his good hands, game awareness, and athleticism on the mound.

He’s not the headiest baserunner, but his speed is far above average (28.8 feet per second per Statcast, roughly as fast as Chris Taylor or Akil Baddoo) and he stole 26 bases last year while leading the majors with eight triples.

And, of course, he’s an elite power hitter (.592 SLG, 158 OPS+, 46 HR, 318 TB in 2021) and a dominant starting pitcher (141 ERA+, 29.3 K% in 23 starts). No one in either league can compete with Ohtani’s ability to be more than 40 percent better than the average hitter and the average pitcher while taking on a full workload on both sides of the ball. In fact, no one in the history of the American and National Leagues can compete with that. The big question is thus, can he do it again. His attempt to do so starts on Opening Day, April 7, at home against Framber Valdez and the defending AL champion Astros. Circle that one on the schedule.

National League: Fernando Tatis Jr., SS, Padres

Am I overreacting to Mookie Betts’ having a relative down year at the age of 28? Am I overreacting to just how exciting Tatis is to watch and ignoring how fragile he has proven to be thus far in his career, hitting the injured list six times since 2018 with a broken thumb, hamstring strain, bad back, torn shoulder labrum (twice in a shoulder prone to popping out of the socket), and now a fractured scaphoid bone in his left wrist that will cost him the first half of the season? I don’t think so. In his first three major-league seasons, Tatis has hit .292/.369/.596 (160 OPS+) while averaging 48 home runs and 31 stolen bases (at an 81 percent success rate) per 162 games, and has played all but 26 of his games at shortstop. He’s not above average at shortstop, and his many injuries may eventually force him off the position, but he’s an elite power hitter, and an elite baserunner (beyond the stolen bases). And, yes, he’s an absolute joy to watch play.

We won’t get to see Tatis or deGrom until closer to mid-season, which is a huge bummer, especially for Padres and Mets fans, but I do not believe that either will return diminished, and I eagerly anticipate their returns, even if I know better than to do so.

Major Leagues: Ohtani

Best Team

American League: Blue Jays

The Jays have the best lineup and the best rotation in the league, but they only just edge the White Sox in my estimation. That’s because Chicago isn’t far behind in either of those categories and I have more faith in the Chisox’s bullpen. Of course, the Blue Jays play in the league’s most competitive division, while the White Sox play in a division that, a year ago, had no other winning team. With this being the final year of the heavily imbalanced schedule, the final win totals may not be enough to determine which team really was the best by year’s end, and the same can be said of the playoffs, but, at the very least, I expect these two teams to win their divisions, and that’s a much more lofty prediction for the Blue Jays than the White Sox give their competition.

National League: Dodgers

The Dodgers’ rotation is a bit thinner than we’re used to seeing it, and I wouldn’t expect much out of Dustin May (who had Tommy John surgery last May) or Trevor Bauer (who may never throw another pitch for the Dodgers). Still Walker Buehler, Julio Urías, Clayton Kershaw, Tony Gonsolin, and David Price hardly comprise a second-rate rotation, and Kershaw has been sharp this spring. The lineup is the best in the majors. The bullpen was greatly improved (at least relative to where it was a week ago) by the Kimbrel trade. The Dodgers won 106 games last year, and their division looks less challenging heading into the year than it proved to be last year. I think the Mets and Braves are both very good teams, but I don’t think either is better on paper heading into the season than the Dodgers.

Major Leagues: Dodgers

Feedback

I want to hear from you. Got a question, a comment, a request? Reply to this issue. Want to interview me on your podcast, send me your book, bake me some cookies? Reply to this issue. I will respond, and if I find your question particularly interesting, I’ll feature it in a future issue.

You can also write me at cyclenewsletter[at]substack[dot]com, or @ me on twitter @CliffCorcoran.

Closing Credits

I was a big fan of Cracker’s debut single, “Teen Angst (What the World Needs Now),” when it came out in 1992, but I didn’t bother to buy any of the band’s music until picking up their sophomore album Kerosene Hat, and it was only after that that I doubled back to Camper Van Beethoven, lead singer and principle songwriter David Lowery’s first, more influential, and more highly regarded band. I dig CVB, but I still have a soft spot for Kerosene Hat, best known for the hit single “Low,” even if the songs are more conventional (honestly, probably in part because the songs are more conventional), but also now out of nostalgia, as Cracker was the rare ’90 band that didn’t take itself too seriously (that was what got me hooked on that initial single, which teases the burgeoning grunge movement right there in the title).

I mention that here to introduce a Lowery-penned song that is very conventional and only seems to be unserious. It’s “I Want Everything,” which is kind of the “Everybody Hurts” of Kerosene Hat, a big, conventional ballad from a band still clinging to some college rock credibility that works almost despite itself because it’s genuine. Lowery’s verses border on nonsense, but the longing is still obvious and explicit ('“I’m waiting for you desperately”), and chorus is vague enough to convey a rather pure emotion that held a particular appeal the the 17-year-old I happened to be when I first got this album:

All things beautiful

All things beautiful

I want everything

To my ears, it’s a song of hope and optimism, impatience, and longing to get out in the world and experience what life has to offer. After the abbreviated 2020 season and this winter’s lockout, that’s how I feel about the 2022 baseball season. I want all things beautiful. The best of everything.

The Cycle will return before Opening Day with some more preview material. In the meantime:

The Nationals should've gone with DC on their City Connect jerseys. I'm biased, because those are my initials, but I miss their DC alternate tops. And as for the rollout -- 14 teams through this year, with 16 more to come next year -- that could be a result of the manufacturing issues stemming from the pandemic. It's why a few NFL teams have announced alternate uniforms for 2023 -- they wanted to have them for the 2022 season, but supply-line issues have made that target unreachable.

Also, good thought in that they should've been pink on white (or a slightly off-white marble-like color). I, too, think the slate gray is ridiculous and they should've embraced the pink more. The Wizards' design is much better just for that reason (if maybe a little too far in that direction).