The Cycle, Issue 121: Cancel Culture Run Amok

MLB cancels regular-season games, Derek Jeter quits the Marlins, Josh Jung out six months; Plus, is Topps' 2022 design its best of the last decade?

In this issue of The Cycle . . .

A Quick Note: Sorry about last week

What You Need to Know: MLB cancels regular-season games, Derek Jeter leaves Marlins, Josh Jung out six months

Topps

1011: Where does the 2022 Topps design rank among the last 11 years.Feedback

Closing Credits

A Quick Note

My apologies for the lack of an issue last week. I don’t have good excuse, so I won’t make one, but remember that I still have the pay switch turned off, so no one was charged for anything they didn’t receive. Tuesday’s break in the labor negotiations gave me a good opportunity to jump back in here, so I’m doing so, but my planned look at New Era’s Spring Training caps will have to wait for now (possibly for major-league Spring Training to be back on the schedule). Today’s issue is strictly news and baseball cards (with a little music at the end, of course).

What You Need to Know

MLB Cancels First Two Regular-Season Series after Arbitrary Tuesday Deadline Passes with No Deal

The nine days of daily labor negotiations from Monday, February 21, to Tuesday, March 1, were a journey. Things started out mildly optimistic, in part because the players and owners had finally decided to get down to work with daily meetings. Initially, the two sides alternated making small concessions, but, as each side became increasingly discouraged by insignificance of the other’s movement, those concessions got smaller and smaller.

Last Wednesday, the owners set a February 28 deadline for having a deal in place without cancelling regular-season games. On Thursday, after the players presented a counteroffer with only minute changes from their previous offer on Tuesday, the owners, whose concessions to that point had been no more significant and arguably less so, claimed to be “out of ideas.”

On Friday, the league cancelled exhibition games through March 7. However, that same day, commissioner Rob Manfred made his first appearances at the negotiations and had his first one-on-one meeting with Players Association Executive Director Tony Clark since 2020. On Saturday, the players came to the table with some significant concessions, particularly a big reduction in their request to expand Super Two arbitration eligibility, but were rebuffed.

Enraged, the players threatened to walk away from the bargaining table, but they returned on Sunday. The lack of public details about Sunday’s negotiations was viewed, with cautious optimism, as a possible sign of real progress. With the owners’ deadline looming, the two sides engaged in a marathon series of negotiations on Monday, spilling into the wee-morning hours on Tuesday and appearing to make some real progress. Among other things, they reportedly came to terms on a 12-team playoff field and the universal designated hitter, while the players and owners dropped their requests to, respectively, expand arbitration eligibility and increase the competitive-balance-tax penalties. In the process, the owners extended their deadline to 5pm ET on Tuesday.

Still, the two sides remained far apart on several core economic issues, and we learned later that the owners made late attempts to shoehorn some of Manfred’s pet projects—including a pitch clock and limitations on shifting—into the deal. Rather than pick up where they left off on Tuesday morning, working toward a resolution with a willingness to extend the deadline, the owners made the players an ultimatum, a take-it-or-leave it “best and final offer” just prior to the 5pm deadline. The players rejected it unanimously, and the owners responded by announcing the cancellation of the first two series of the regular season (as well a further official delay of the start of the exhibition schedule to at least March 12).

The players denounced the owners’ deadline as arbitrary and unnecessary (which it was) and accused the owners of trying to break the union, but nonetheless remain ready to continue negotiations. The owners, however, have said they won’t resume talks until at least Thursday.

Among the issues on which the two sides remain far apart are the size of the pre-arbitration bonus pool (owners: $30 million; players: $85 million), the major-league minimum salary (owners: $700,000 this year to $740,000 in 2026; players: $725,00 this year to approximately $795,000 in 2026), and the competitive-balance-tax thresholds (owners: $220 million this year to $230 million in 2026; players: $238 million this year to $263 million in 2026).

Some Context

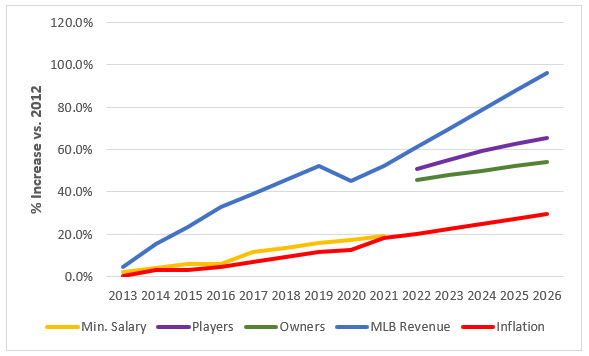

To give you a sense of how those proposals fit into the game’s larger economic structure, let’s revisit the graph I used in Issue 119 to illustrate the increasing discrepancy between the owners’ revenues and the cost controls placed on players’ salaries. As a refresher, here’s that graph again:

That graph uses 2012, the first year of the 11th Collective Bargaining Agreement, as a baseline and charts the percentage of growth of league revenues, the MLB minimum salary, the CBT threshold (the last two per the terms of the CBAs), and inflation relative to 2012. Even a small child could tell you that one of those things is not like the others.

Now, let’s project things over the five years likely to be covered by the next CBA. With regard to league revenues, 2020 and ’21 were abnormal because of the pandemic, but recent financial disclosures by the publicly held company that owns the Braves suggest that the league made a full recovery from 2020 last year, so I’ll project revenues forward using the average annual increase from 2013 to 2019, which is 8.8 percent. Similarly, I’ll use the average annual increase in inflation (1.9 percent) to project that forward. The CBT thresholds are actual numbers. Through 2021, they are the thresholds outlined in the last two CBAs. From 2022 forward, there are two lines: one for the owners’ proposed thresholds (in green) and one for the players’ proposal (in purple):

As you can see, the owners’ proposal continues to represent little more than a cost-of-living increase, if that. Even the players’ proposed thresholds increase at a rate more comparable to that of inflation than the league’s projected revenues. The Year One increase from the players’ latest proposal doesn’t even make up half of the ground the players have lost relative to the growth of league revenues since 2012, and that gap is likely to only increase even if the owners conceded to the players’ demands. By 2019, league revenues had increased 52.3 percent relative to 2012. If the owners concede to the players’ most recent CBT-threshold demands, that threshold will still have increased just 47.8 percent from 2012 to 2026 (while league revenues will continue to grow despite the damage done by the current lockout, which is the owners’ own fault to begin with).

I should note here that, in the graphs above, I prorated MLBs revenues in 2020 to 162 games (because the terms of the CBA are all based on a 162-game season, player salaries were prorated down to 60 games that season, and I wanted to keep everything in these graphs on the same scale). Meanwhile, because we don’t have official figures for 2021, I simply reused the revenue figure from 2019 for 2021, based in part on the Braves’ disclosures. The upshot of all of that is that, even after a dip in revenues in 2020 and what amounts to a flatline from 2019 to 2022, league revenues still project to continue racing away from the salary constraints placed on the players.

Should we do the league minimum salary? Here’s that:

That’s quite an improvement in terms of the initial jump, but the rate of increase still hews much closer to inflation (the players’ 2025 and ’26 proposals are, in fact, just a cost-of-living increase). What’s more, the gap between the increase in league revenues and the codified salary constraints widens yet again as the proposals advance in time. Viewed this way, it seems silly for the two sides not to simply meet in the middle (to be fair, they have made quite a bit of progress toward that on this issue). However, given the context of that top line, I fail to see why the players should conceded any further on this issue.

Now What?

Hopefully the two sides will reconvene tomorrow, if not soon after, and pick up where they left off in terms of protracted daily negotiations. The only way we’re getting baseball back is for the negotiations to continue, and with both the exhibition and regular-season schedule now altered (exhibition games were originally scheduled to start last Saturday), every day of delay, such as the owners’ refusal to meet today, could mean more games lost.

Meanwhile, as we just saw in 2020, the length of the season and its impact on the players’ compensation will need to be collectively bargained, as well. So, while the owners claim that they have cancelled those 91 games outright and will not make them up nor compensate the players for them, they’ll ultimately need the players to agree to a revised schedule. Meanwhile, the players previously threatened to pull expanded playoffs off the table if any regular-season games were cancelled without the players being compensated.

I do think we could wind up losing a month or more of the regular season, but the players still have that playoff card to play, and, while it’s possible that the owners and league executives just don’t care, public opinion has only shifted harder against Manfred, the league, and the owners in the wake of Tuesday’s decision, as evidenced by the virality of that photo above.

Derek Jeter to Resign and Devest from Marlins

Derek Jeter and the Miami Marlins announced on Monday that Jeter was resigning as the team’s CEO and head of baseball operations and would also divest from ownership. Jeter owned approximately four percent of the Marlins as part of the ownership group that bought the team from Jeffrey Loria in August 2017. Per subsequent reports and a close reading of Jeter’s press release, it seems Jeter is leaving due to frustration over principal owner Bruce Sherman’s refusal to expand payroll in what Jeter believes are the late stages of the rebuild the group initiated upon buying the team.

You’ll recall that, almost immediately after Jeter and Sherman purchased the team, the Marlins sold off their All-Star outfielders Giancarlo Stanton, Christian Yelich, and Marcell Ozuna, then traded All-Star catcher J.T. Realmuto a year later. Confronted about the fire sale at the time, Jeter spoke of a long-term plan to build a sustainable winner. The first indication that Jeter’s plan might be working was the team sneaking into the expanded playoffs in 2020 in conjunction with the emergence of an impressive young rotation headed by Sandy Alcantara (acquired in the Ozuna trade), Pablo López, and 2021 Rookie of the Year runner-up Trevor Rogers (both acquired under Loria), with other highly regarded young pitchers at or near the major-league level.

In November, the Marlins bought out two of Alcantara’s free-agent seasons and secured a club option on a third via a $56 million extension, a significant move for a franchise with a history of trading its stars when they reach arbitration. They then signed free-agent outfielder Avisaíl García to a four-year, $53 million contract. Still, the Marlins’ projected payroll for 2022 remains near the bottom of the league, below both $70 million and the Marlins’ own 2019 payroll. Jeter reportedly had hopes of the team making additional free agent signings in the wake of the lockout, with free-agent outfielder and Miami-area native Nick Castellanos a known target, only to be told more recently that would not happen. As Jeter said in his statement on Monday, “the vision for the future of the franchise is different than the one I signed up to lead.”

I envisioned something like this happening nine years ago, when Jeter was in the waning days of his playing career. Looking ahead to Jeter’s retirement, I knew of Jeter’s desire to own a team but had trouble envisioning him rolling with the struggles of the kind of team that typically comes up for sale. As I put it then, “What happens when Derek Jeter discovers that he doesn’t have as much control over his ability to succeed as he thinks?”

I think we now have our answer.

Beyond Jeter, this is awful news for Marlins fans. In Jeter, they had an executive who, despite the initial sell-off, was clearly determined to build a long-term winner and to turn the long-floundering Marlins into a formidable franchise. With his departure, they not only lose that executive, but lose him because of the greater power wielded by an owner who clearly didn’t share that determination. Jeter did leave the Marlins in the hands of a capable and groundbreaking general manager in Kim Ng, but if the battle between Jeter and Sherman was between spending to win and a more familiar form of penny pinching, this is an ominous event for Marlins fans.

Rangers 3B Prospect Josh Jung Out Six Months After Shoulder Surgery

This is a bummer. Jung is a top-30 prospect leaguewide (#26 per Baseball America, #31 per Baseball Prospectus) and was expected to take over at third base for the Rangers early this season, joining big-name free agents Corey Seager, Marcus Semien, and incumbent first baseman Nate Lowe in forming a infield quartet that the Rangers believe could power their next contending team as early as next year. Instead, Jung tore the labrum in his left shoulder lifting weights in preparation for the season and will miss six months following surgery last Wednesday to repair the joint.

Six months from that surgery is the end of August, so this injury will very nearly wipe out Jung’s entire season and effectively delay his major league arrival by a year. That’s a lost year of development for a top prospect, but also a lost year of adjustments at the major-league level that could have set Jung up to be an impact player for the Rangers next year, when they hope to actually contend.

The ninth-overall pick in the 2019 draft, Jung hit .326/.398/.592 in 78 games split between Double- and Triple-A last year, performing even better at the higher level, and is career .322/.394/.538 hitter in a minor-league career interrupted by the pandemic in 2020. He’s also a college product who turned 24 earlier this month and thus will be 25 next year when he finally (hopefully) gets an extended big-league opportunity. To put that in context, Jung is eight months older than Juan Soto, nearly a year older than Fernando Tatis Jr., and less than two months younger than Ronald Acuña Jr. He is thus not a blue-chipper on that level, but the Rangers do hope he will be an impact bat in the middle of their lineup. Unfortunately, they’ll have to wait another year to find out if he can continue on that trajectory.

Pop of the Topps: The 2022 Design

In something of a bitter irony, on the same day that the first games of the 2022 season were cancelled, I received Series 1 of the 2022 Topps set in the mail. Usually, that first batch of baseball cards is a rite of spring, along with the return of robins and other songbirds, the emergence of crocuses, and the arrival of pitchers and catchers. I suppose three out of four ain’t bad, but the one that’s missing is a biggie.

Still, I have 330 new baseball cards to peruse, and I’m quite pleased by the design of this year’s Topps set. Almost exactly a year ago, I got my first pack of 2021 Topps and set about raking the design of the previous decade of Topps cards (2012–2021) in Issue 18 of The Cycle. I put 2021 pretty low on that list (seventh), and my fondness for that design has only decreased in the last year. I’m curious to know what I’ll think about the 2022 design after spending a similar amount of time with it, but my initial impression is very favorable. In fact, I’d say the only design that rivals it since 2012 is the one I ranked first on that list: the 2013 design.

Which is better? I may need some time to decide, but as an addendum to last year’s list, here’s a sort of tale of the tape of the 2013 and 2022 Topps designs, once again using Clayton Kershaw’s card to represent the set:

Let’s start with some of my pet peeves:

Logo/Team Name Redundancy: The 2020 set was the first since 2013 not to unnecessarily print the team name on a card front that already displayed the team logo. I was optimistic that would be a lasting change, but the redundancy is back this year for the eighth time in the last nine years. It’s relatively inoffensive in the 2022 design, but this is still: Advantage 2013

Picture Obscuring Clouds: Topps started this nonsense in 2015 but seemed to leave it behind in 2018. Its return is very disappointing and is the biggest strike against the 2022 design, which features a completely unnecessary fog at the bottom of the photo which bleeds out into the design itself making the player’s position in the lower right very difficult to read: Big Advantage 2013

Random Shapes: This is a minor violation, but, in the 2022 design, what is the point of that circle on the upper right of the baseball graphic with the team insignia? Advantage 2013

Foil: Topps spent two full decades rendering player names and such in foil. The 2013 set was the penultimate set in that period. You can’t tell from the scan, but the player names on those card are in foil, which can make them invisible from certain angles. Advantage 2022

Wasted Space: One of the 2022 design’s biggest strengths is that it is tidy and, outside of the cloud, the design is unobtrusive. The 2013 design, on the other hand, creates an awkward bottom border from its attempt to force a field shape into the design. The biggest problem with that is the wasted pace on the lower right of the card, which requires those faint horizontal lines so it won’t look so empty. Advantage 2022

Logo Size: Relatively speaking, the interlocking LA on the 2013 card is too big, again trying to compensate for that wasted space in the lower left. Advantage 2022

Logo Choice: In recent years, many teams have made some version of their cap insignia their primary logo. I much prefer the teams’ more ornate logos (the Yankees’ top-hat logo, the Mets’ skyline logo, the Dodgers’ flying baseball logo, etc.). Last year, Topps used many of those preferable logos on their cards. This year, they have reverted to the cap logos for every team but the Cubs and Rangers, but it makes sense to do so on the context of the design. Many team logos use a baseball as a background or are otherwise baseball shaped and would thus look odd or redundant on the baseball design in the lower left of the 2022 cards (as, indeed, the Cubs’ and Rangers’ logos do). The cap insignias are a better choice for this specific design. The 2013 cards mixed things up a bit more, but used the cap insignias far too often for a design that didn’t motivate doing so. Advantage 2022

Color Palate: The 2013 cards could be monochromatic, because the base design used just one team color, and that was often the lone (or dominant) color used in the team insignia, as well. The 2022 design uses the two primary team colors, the darker one behind the player name, and the lighter one for the trim around the photo and stitching of the baseball. That’s a big improvement, particularly as that lighter color is often complimentary to the color of the insignia, as is the case for the Dodgers, as seen above. That makes the design really pop despite the best efforts of those darn clouds. Advantage 2022

Photography: Best I can tell, the photos in the 2022 set are crisp and clean (behind those clouds). From the cards I’ve seen thus far, I haven’t seen any heavy filter use. The photos look good, as was the case in 2013. Push

Cropping: In the mid-2010s, Topps went through phase in which it cropped many of the photos on its cards too close, cutting off the players’ limbs and leaving just a head and torso, even in action shots. That hadn’t taken hold quite yet in 2013, but you can see it coming. The photos that year are cropped a bit closer than was typical in action shots from the previous four decades. In recent years, Topps has been zooming back out to good effect, and while this is another thing I won’t get the full sense of until I have the full 660-card set in an album, it looks as though the 2022 set gives the players more room than the 2013 did. The contrast between the two Kershaws above seems to be representative of that difference. Advantage 2022

Conclusion: If it weren’t for those darn clouds, I would easily list the 2022 design ahead of 2013. With the clouds, I’m torn. The basic design elements of the 2022 cards are really sharp. I like the colors, I like the baseball graphic. In fact, I’d go as far as to say that the 2022 baseball graphic is the best incorporation of piece of baseball equipment into the basic design of a Topps set in the company’s history (not that there’s much competition, really just the 1981 caps and the 2013 fields, unless you want to count the jersey-script-like design of 1989 and various pennant-like banners, the best of which was on the 1965 cards). However, I hate, hate, hate, hate those clouds. For now, I’m going to put 2022 just behind the 2013s, though I reserve the right to adjust that ranking when the 2023s come out.

Feedback

I want to hear from you. Got a question, a comment, a request? What would you like to read about in lieu of actual baseball news? Reply to this issue. Want to interview me on your podcast, send me your book, bake me some cookies? Reply to this issue. I will respond, and if I find your question particularly interesting, I’ll feature it in a future issue.

You can also write me at cyclenewsletter[at]substack[dot]com, or @ me on twitter @CliffCorcoran.

Closing Credits

In 1958, Paul Anka, a 17-year-old Lebanese-Canadian teen idol who would ultimately make his biggest impact on pop music as a songwriter, toured the UK and Australia with Buddy Holly. That year, Anka wrote “It Doesn’t Matter Anymore” for Holly. Holly released the song in January 1959, less than month before his death in a plane crash, and the song became a posthumous hit. Anka donated his royalties to Holly’s widow, María Elena Santiago.

A decade and a half later, Linda Ronstadt, a torch singer from Arizona who fell in with the Southern California folk- and country-rock scene of the late ’60s and early ’70s, developed a habit of covering Buddy Holly tunes. In late 1976, she reached number 11 on the Billboard Hot 100 with “That’ll Be The Day. ” A year later, she got to number five with “It’s So Easy,” a song that failed to chart for Holly. Prior to either of those, however, she covered “It Doesn’t Matter Anymore” on her breakout album, 1974’s Heart Like a Wheel, placing it second on the album, right after her number-one hit cover of “You’re No Good,” and releasing it as the B-Side of her hit cover of the Everly Brothers’ “When Will I Be Loved” in early 1975.

Although “It Doesn’t Matter Anymore” is a breakup song that became intertwined with an infamous tragedy, Holly couldn’t have anticipated the latter, and his version of the song buries its melancholy under a bouncy, upbeat shuffle and plucked-strings. The arrangement sounds like something out of a 1950s commercial for kitchen appliances or a reminder to go to the lobby for refreshments. It is not, in Holly’s hands, a particularly sad song.

Ronstadt’s version, arranged at least in part by Andrew Gold (best known today for writing “Thank You for Being A Friend,” later used as the theme for The Golden Girls), puts the melancholy out front by reinterpreting the song as a country ballad. Her version opens with Ronstadt’s gorgeous voice over arpeggiated acoustic guitar, later complimented by a subtle rhythm section, a bit of harmonica, strings, and a lovely pedal steel solo by the Flying Burrito Brothers’ Sneaky Pete Kleinow.

That I settled on this song for the Closing Credits of this issue last week may help explain why I didn’t wind up publishing an issue until today. These lyrics translate pretty well to how I was feeling about Major League Baseball late last week, right down to it driving me crazy last September and wasting all my days and nights:

Do you remember, baby, last September

How you held me tight each and every night

Oh, baby, how you drove me crazy

But I guess it doesn’t matter anymore

There’s no use in me a-cryin’

I’ve done everything and now I’m sick of trying

I’ve thrown away my nights, wasted all my days over you

Now you go your way, baby, and I’ll go mine

Now and forever till the end of time

And I’ll find somebody new and baby

We’ll say we’re through and you won’t matter anymore

Below I’ve included both the studio version and a live performance from 1977, played at an even slower tempo, which replaces the strings and harmonica with an electric piano and features Ronstadt on acoustic guitar (once she removes all of her chunky bracelets and muses about panty girdles, that is).

The Cycle will return . . . soon. I’m eager to find the best card in the 1983 Topps set, but the pace of the labor negotiations may determine the date of the next issue, as was the case this week.

In the meantime, thanks for reading:

2022 Topps … I can easily read player names! It’s a big win. Funny enough, the “too much white space” at the bottoms of the 2013s bugs me in the same way the cloud bugs you on 2022. I don’t like the cloud effect, but, the TMWS bugs me more. Overall, 2022 has a nice, clean design. As for MLB and the owners … the less *&$#% I *&$#% say on the matter, the better. *&$#%!!!