The Cycle, Issue 120: Lockout Workout

Counterintuitive optimism about the labor negotiations, does baseball have an opioid problem?, MLB attacks mLers, the dean of every team, and the best Topps card of 1982

In this issue of The Cycle . . .

What You Need to Know: Labor update, Skaggs trial, MLB’s attacks on minor leaguers

Team Deans: The longest tenured active player with every MLB team

Pop of the Tops: Finding the best Topps card of 1982

Feedback

Closing Credits

What You Need to Know

Pitchers and catchers would have reported to major-league camps this week but did not because of the owners’ lockout. Exhibition games were scheduled to start a week from tomorrow, on February 26, but it seems safe to say they will not because of the owners’ lockout. The most recent offers from both sides have shown very little movement toward compromise. However, in the wake of the union’s most recent offer on Thursday, some signs emerged that suggested that owners are starting to feel the heat of the approaching regular season and that meaningful movement may be possible next week.

Collective Bargaining to Accelerate Next Week

The owners didn’t budge much in their offer to the players last Saturday and actually increased the severity of the competitive-balance-tax penalties relative to their previous offer while continuing to propose threshold increases that fall short of expected inflation. The players delivered their counterproposal on Thursday and didn’t budge much, either, making no changes to their previous competitive-balance-tax proposals and actually increasing the size of their proposed pre-arbitration bonus pool, from $100 million to $115 million (the owners increased their proposed pre-arb bonus pool from $10 million to $15 million on Saturday).

However, the players did back off their demand to make all players arbitration eligible after two years of service time, proposing instead to expand Super Two eligibility from the current top 22 percent of players with between two and three years of service time to the top 80 percent. That’s a strong signal of a willingness to compromise on that front, and I hold out hope that the two sides can meet in the middle on that as well as the many other economic issues on which their differences are those of degree rather than principle.

On a similarly optimistic note, in the wake of the players’ proposal on Thursday, the two sides both signaled their awareness of the increasing urgency of working out a deal. The owners reportedly informed the players that a deal would need to be agreed upon by February 28 (which is a week from Monday) to avoid altering the regular-season schedule, and the two sides are now planning more frequent talks next week, and may meet as often as daily starting on Monday. To add to the urgency, the union has reportedly told the league that it won’t approve expanded playoffs for this season if any regular-season games are cancelled due to the labor dispute.

Finally, Thursday night, Ben Nicholson-Smith of Sportsnet tweeted this: “per sources: MLB has indicated some flexibility exists beyond its current offers. Particularly on CBT and in getting younger players paid.” The cynical view of that tweet is that MLB has to be flexible beyond its current offers. However, the explicit mentions of two of the unions’ top priorities allows for a more optimistic reading.

Next week should be interesting.

Eric Kay Guilty on Both Counts; Trial Outs Opioid Use by Former Angels Players

Former Angels communications director Eric Kay was found guilty on Thursday of both possessing a controlled substance with an intent to distribute and of providing Tyler Skaggs with the fentanyl-laced counterfeit pills that caused the former Angels lefty’s fatal overdose last July. The Fort Worth, Texas, jury deliberated for less than 90 minutes before delivering its verdict on Thursday.

During the trial, five former Angels—current Rockies first baseman C.J. Cron, current Phillies minor leaguer Cam Bedrosian, and free agent pitchers Matt Harvey, Mike Morin, and Blake Parker—took the stand and admitted to the illegal usage of opioids provided by Kay. Harvey, who received immunity in exchange for his testimony, also admitted to sharing pills with Skaggs—including Percocet, which contains oxycodone, another drug found in Skaggs’ system when he died—and to his own past use of cocaine. Despite Harvey’s legal immunity, he could face a suspension from MLB as a result of his admissions, as the Joint Drug Agreement prescribes a 60- to 90-day suspension for distribution. Given that Harvey will turn 33 next month and was one of the worst pitchers in baseball last year, the threat of that suspension could prove to be career-ending.

Beyond the details of the Kay trial, the testimony of those players suggests that there maybe a larger opioid problem in baseball of which we’re not aware. That would only make sense given the country’s larger opioid epidemic. The players who testified in Kay’s trial spoke of battling aches and pains as well as the mental stressors of their profession. The Joint Drug Agreement does not make first offenses public, so it’s possible that there are things happening behind the scenes of which we’re not aware. The Athletic’s Ken Rosenthal digs into the issue here.

The most important thing, after identifying the players who are using and abusing and getting them the help that they need, is to talk about this compassionately. “Recreational” is a misnomer. These players were self-medicating, and it is not just the drug use, but the underlying issues that prompted it that need addressing, be it in the individual cases or in the league as a whole. Opioid abuse is bad news not because it’s “immoral” but because of the actual physical danger involved. Indeed, this is all coming to light because a healthy, strapping, 27-year-old major-league pitcher died from using these drugs. As is true for society’s relationship to drug abuse as a whole, MLB should treat this as a health issue, not a discipline issue, and those of us who discuss it should do so with understanding and compassion.

MLB’s Bald Villainy Regarding Minor Leaguers

Major-league team’s mistreatment of minor leaguers is nothing new. Indeed, to my surprise and delight it was the issue of greatest concern among The Athletic’s readers in a recent poll on the state of baseball. MLB finally made some progress on that front in November, introducing a new Minor League Housing Policy, though many minor leaguers and their advocates remain skeptical about its implementation and point out that it’s only effective for single players and does nothing to improve the lives of players with families.

Still, if that was one step forward, MLB took two steps back with regard to its treatment of minor leaguers in the last week. First, per The Athletic’s Evan Drellich, a lawyer for MLB, argued in federal court last Friday that minor leaguers should not be paid during spring training because they are already benefitting from the extremely valuable training they receive, completely ignoring the value the team derives from the players. Per Drellich, “MLB hired an expert at a rate of $775 per hour who argued that players in spring training actually receive a value of $2,200 weekly from their teams, based on what youth and amateur players pay for baseball training.” Just to be clear, the benefit that MLB claims these players are deriving over a full week is worth less than what MLB paid that expert for three hours of research. The hypocrisy is jaw-dropping.

As if that weren’t enough, ESPN’s Jeff Passan reported on Monday that the owners’ latest proposal in Saturday included a provision that would have allowed it to eliminate up to 900 minor-league roster spots over the course of the next Collective Bargaining Agreement by dwindling the size of the Domestic Reserve List from 180 players per team to 150. The DRL itself was introduced as part of the minor-league restructuring after the 2020 season, a restructuring which included the elimination of 42 teams and, thus, more than 1,000 affiliated minor-league roster spots.

I cannot understand why MLB is prioritizing this kind of cruel penny pinching when it comes to the minor leagues. As I wrote in the MLBTR Newsletter on Tuesday, “Based on the minor-league minimum salaries, a team can roster 180 minor leaguers for roughly $3 million, which amounts to a rounding error on the contracts the best of those players will earn in their major-league primes. Slashing 30 of those jobs would save a major-league organization less than a half a million dollars.” The return on investment if even one of those players has an above-average major-league career should make the continued investment in minor-league talent a no-brainer.

Just as you increase your odds of winning a raffle by buying more tickets, teams should increase their odds of developing star players by expanding, not contracting, the minor leagues, to say nothing of the added benefit of installing baseball institutions in more cities and small towns across the country to foster a love of the game (or, in business terms, expand the consumer base). Similarly, teams shouldn’t have to think twice about investing in the training, health, and wellness of those players as, again, those investments are likely to be repaid many times over, particularly given the improvements in player-development techniques and technology that have entered the game in recent years.

At the very least, teams should be doing one or the other, going with a quantity or quality approach. To do neither makes absolutely no sense from a baseball or business perspective. It is the definition of penny smart and pound foolish. No, actually, it’s worse. Because in other cases, when factory owners cut corners in the manufacturing process, the product doesn’t quit, advocate against them on social media, and engender the compassion of the higher-end products with whom those owners are currently engaged in a protracted labor dispute.

Team Deans

Ryan Zimmerman retired on Tuesday, ending a 17-year career that spanned the entire existence of the Washington Nationals. Zimmerman was the Nationals’ first-ever draft pick (fourth overall) in June of 2005, their inaugural season, made his major league debut with Washington that September, baptized Nationals Park with a walk-off home run on Opening Day in 2008, and started every game of the World Series when Washington finally won the championship in 2019. He was “Mr. National,” and only one other active player in all of MLB had been with his current team longer at the moment of Zimmerman’s retirement.

That got me thinking. In 1986, Topps used its team cards to honor the “dean” of every team, the most senior of which was Dave Concepción, who made his debut with the Reds on Opening Day in 1970. Which players hold that distinction today?

The following identifies the player who has been with each of the 30 teams the longest, as determined by the date of that player’s first major-league game with that team. To qualify as such, service may be interrupted by injury or demotion, but cannot be interrupted by employment in by another major-league organization. In some cases I have also included un-signed free agents who would qualify if they re-signed with the team in question or the homegrown player (defined as a player acquired as an amateur) who has been with the team the longest. Teams and players are presented in order of seniority.

Cardinals: Yadier Molina

Debut: June 3, 2004 (drafted 2000)

Reds: Joey Votto

Debut: September 4, 2007 (drafted 2002)

Tigers: Miguel Cabrera

Debut: March 31, 2008 (acquired via trade December 2007)

Nationals: Stephen Strasburg

Debut: June 8, 2010 (drafted 2009)

Giants: Brandon Belt

Debut: March 31, 2011 (drafted 2009)

Honorable Mention: Brandon Crawford (debut: May 27, 2011; drafted: 2008)

Rockies: Charlie Blackmon

Debut: June 7, 2011 (drafted 2008)

Angels: Mike Trout

Debut: July 8, 2011 (drafted 2009)

Astros: Jose Altuve

Debut: July 20, 2011 (signed March 2007)

Royals: Salvador Perez

Debut: August 10, 2011 (signed 2006)

Red Sox: Xander Bogaerts

Debut: August 20, 2013 (signed 2009)

White Sox: Leury García

Debut: August 23, 2013 (acquired via trade August 2013)

Guardians: José Ramírez

Debut: September 1, 2013 (signed 2009)

Rays: Kevin Kiermaier

Debut: September 30, 2013

Dodgers: Justin Turner

Debut: March 22, 2014 (signed as free agent February 2014)

Free Agents: Clayton Kershaw (debut: 2008, drafted: 2006) and Kenley Jansen (debut: July 24, 2010; signed: 2004)

Mets: Jacob deGrom

Debut: May 15, 2014 (drafted 2010)

Diamondbacks: David Peralta

Debut: June 1, 2014 (signed July 2013)

Twins: Jorge Polanco

Debut: June 26, 2014 (signed 2009)

Cubs: Kyle Hendricks

Debut: July 10, 2014 (acquired via trade, July 2012)

Homegrown: Willson Contreras (debuted: June 17, 2016; signed: June 2009)

Padres: Wil Myers

Debut: April 6, 2015 (acquired via trade December 2014)

Homegrown: Dinelson Lamet (debuted: May 25, 2017, signed: June 2014)

A’s: Chris Bassitt

Debut: April 25, 2015 (acquired via trade December 2014)

Homegrown: Chad Pinder (debuted: August 20, 2016; drafted: 2013)

Marlins: Miguel Rojas

Debut: June 27, 2015 (acquired via trade, December 2014)

Homegrown: Brian Anderson (debut: September 1, 2017, drafted: 2014)

Phillies: Aaron Nola

Debut: July 21, 2015 (drafted 2014)

Free Agent: Odúbel Herrera (debut: April 6, 2015; Rule 5 draft: December 2014)

Yankees: Luis Severino

Debut: August 5, 2015 (signed December 2011)

Honorable Mention: Gary Sánchez (debut: October 3, 2015; signed: July 2009)

Free Agent: Brett Gardner (debut June 30, 2008)

Rangers: Matt Bush

Debut: May 13, 2016 (signed as FA Dec. 2015; currently non-roster)

40-man: José Leclerc (debut July 6, 2016; signed: December 2010)

Braves: Dansby Swanson

Debut: August 17, 2016 (acquired via trade December 2015)

Free Agent: Freddie Freeman (debut: September 1, 2010, drafted: 2007)

Brewers: Brent Suter

Debut: August 19, 2016 (drafted 2012)

Manager: Craig Counsell has helmed the team since 2015, pre-dating every player on the roster.

Orioles: Trey Mancini

Debut: September 20, 2016 (drafted 2013)

Mariners: Mitch Haniger

Debut: April 3, 2017 (acquired via trade November 2016)

Homegrown: Kyle Lewis (debut: September 10, 2019; drafted 2016)

Manager: Scott Servais has helmed the team since 2016, pre-dating every player on the roster.

Blue Jays: Tim Mayza

Debut: August 15, 2017 (drafted 2013)

Pirates: Colin Moran

Debut: March 30, 2018 (acquired via trade Jan. 2018)

Free Agents: Chad Kuhl (debut: June 26, 2016; drafted: 2013) and Stephen Brault (debut: July 5, 2016; acquired via trade February 2015)

Pop of the Topps: 1982

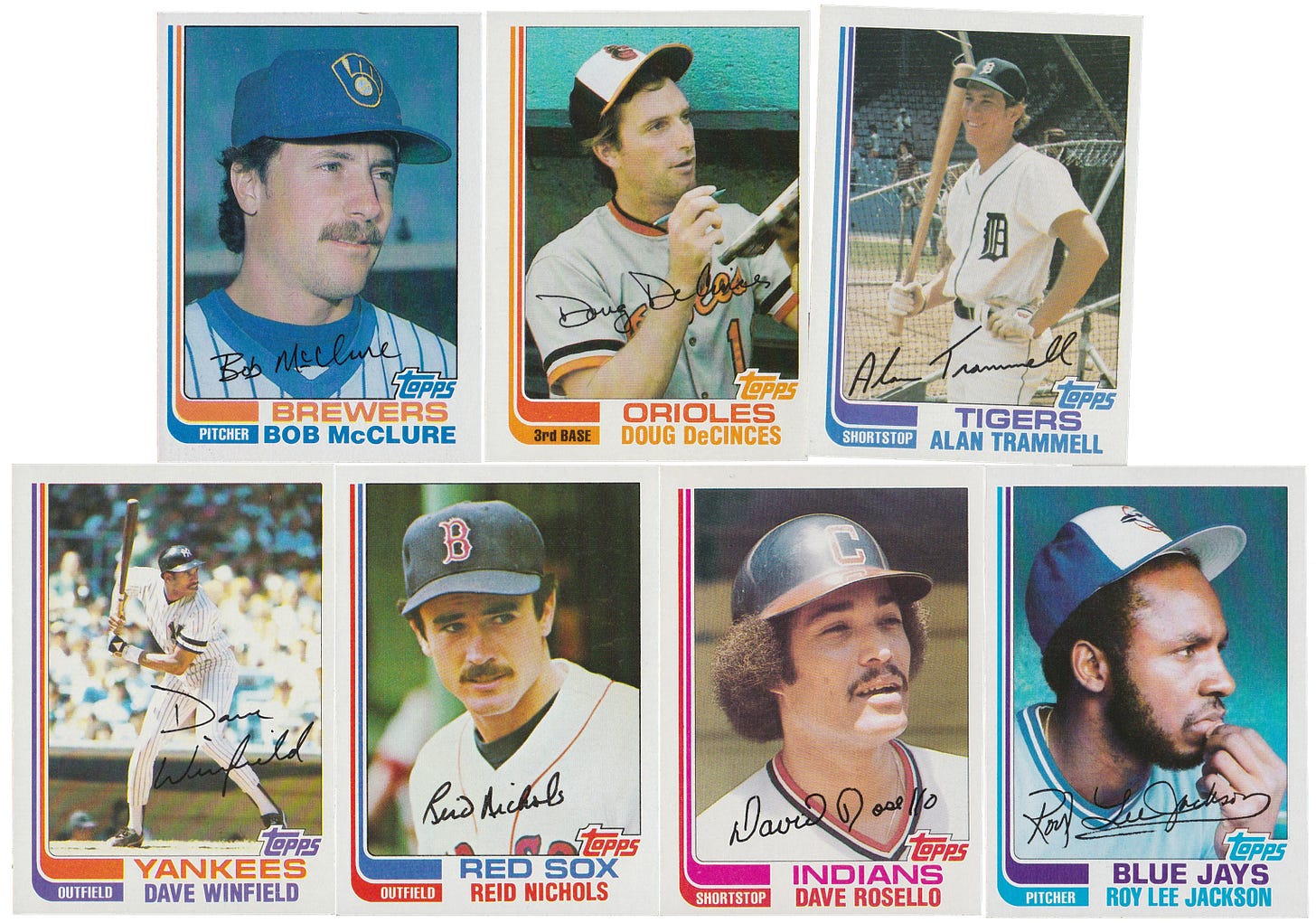

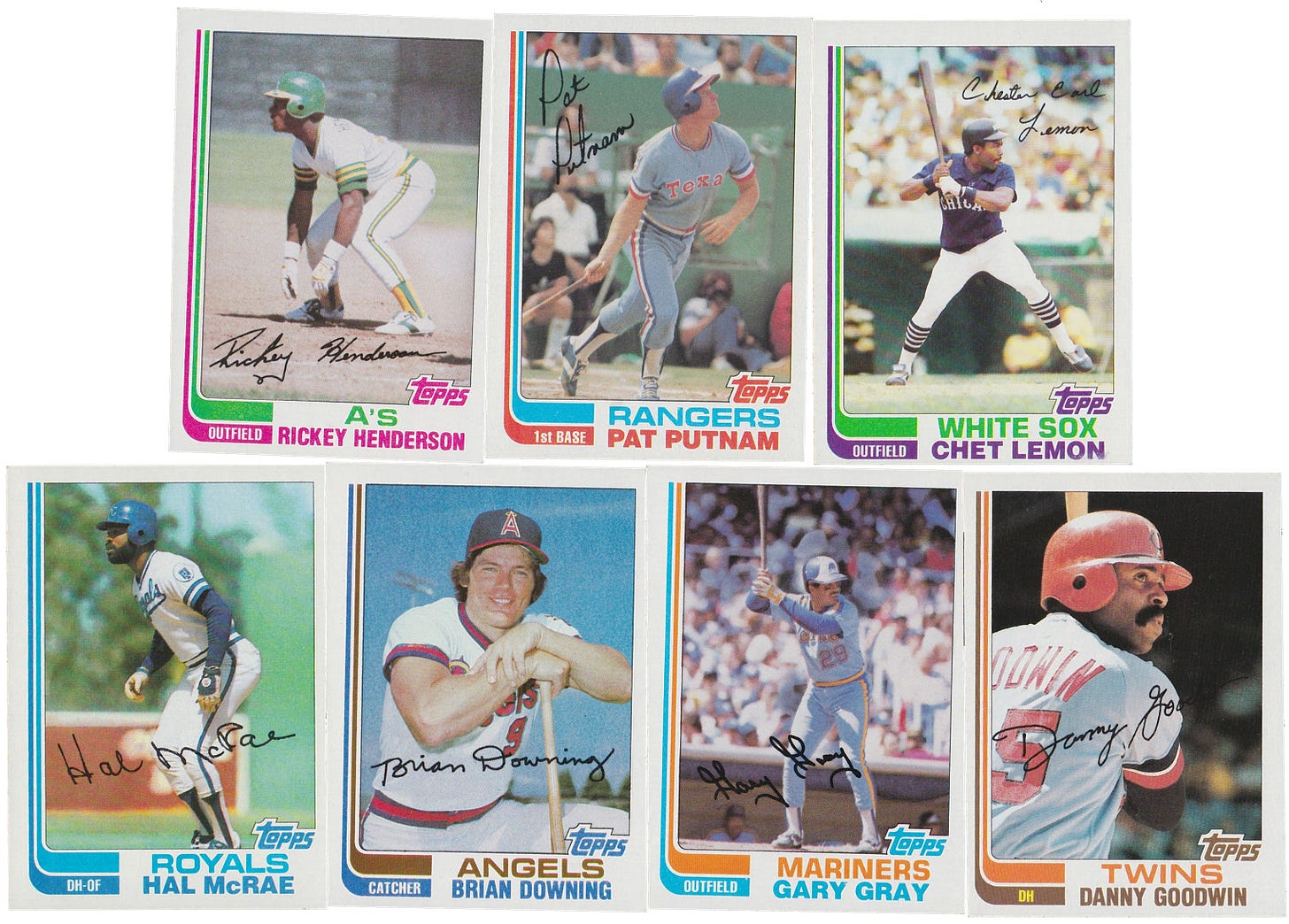

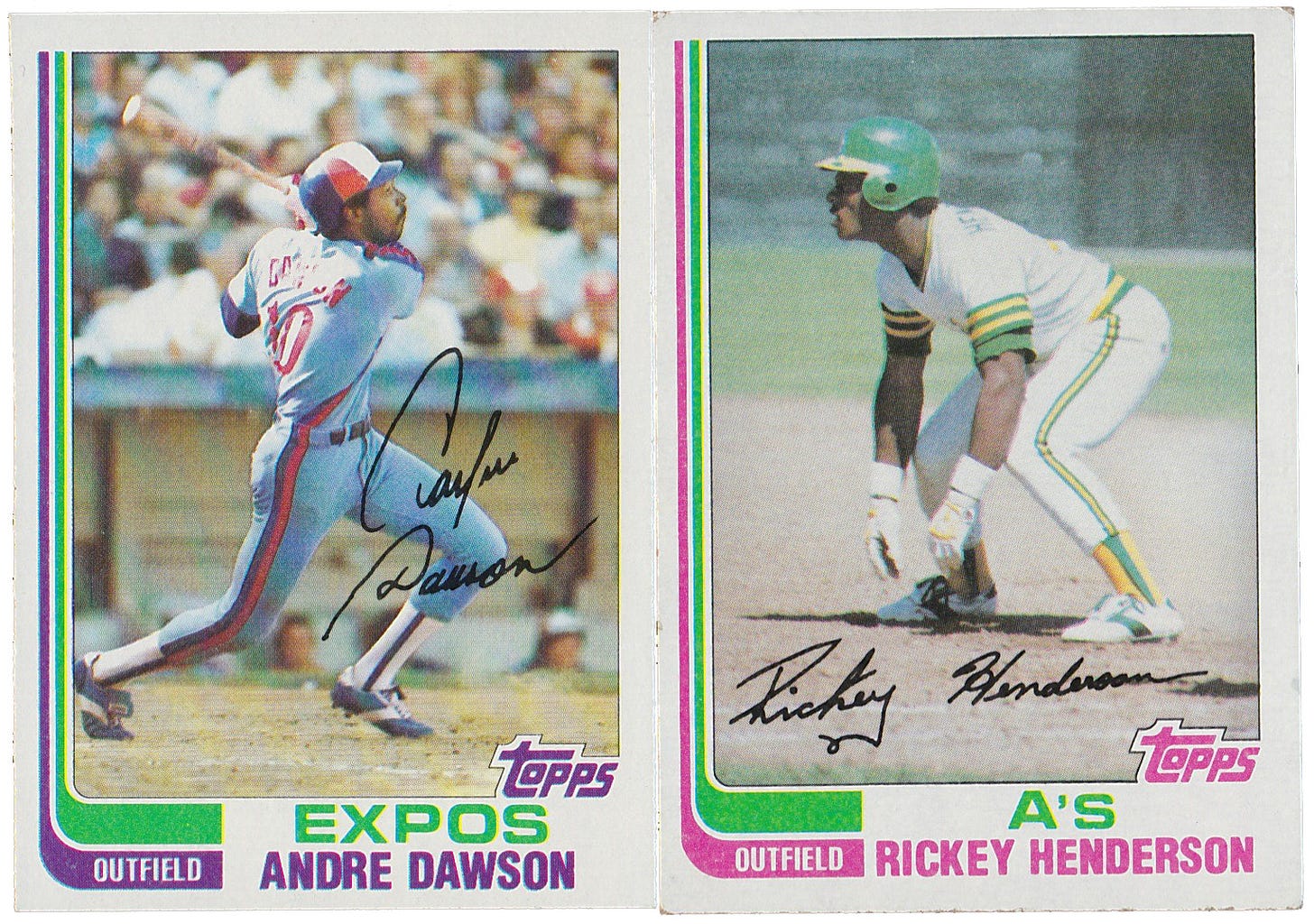

My tournament of the best Topps cards of the 1980s (from the 1981 to 1990 sets) continues this week with a look at the 1982 Topps flagship set. As a young collector in the late ’80s, I always held this set in high regard, both for its sleek design (echoed recently by the 2019 set), and because it was (until 2008) the last set to have printed signatures on the photos. That was before I owned the whole thing. Looking back at it now, the basic design is a huge upgrade on 1981’s goofy nadir, but the set as a whole is not a good one. The photography may actually be worse than the previous year’s, the color schemes for the teams often clash with that team’s actual colors (so much green and brown and orange!), and the signatures just clutter up the photos. This set seems to prefer close-up candids over posed shots, but those are almost all unflattering or out of focus to one degree or another, and they dominate the set, which has fewer action shots than you might expect.

I struggled to find a card from every team worth including in this exercise, and even some cards that I think are well composed fall short in practice. Again, you’ll see what I mean as I unveil my picks for the best card from every team. Again, my criteria here are purely aesthetic. I’m not ranking these cards by potential value or importance. The player pictured barely matters at all (though it certainly can give a boost to an already-handsome card). What matters is that the card has a good photo, well-framed, that fits well within the card’s design. These cards are the ones that come closest to what I think a baseball card should look like. Bright colors, clean, crisp photography with the right amount of light, and some compelling details.

I wonder to what degree that lack of actions shots in the 1982 set was a result of the 50-day player strike which bifurcated the 1981 season. Fewer games may have meant fewer chances to get those photographs, though I’m not sure if that’s entirely true, as I don’t know what Topps’ shooting schedule was for that season. Either way, this set depicts that split season, but the cards below are presented in the order of the aggregate standings from both halves of the season.

National League East

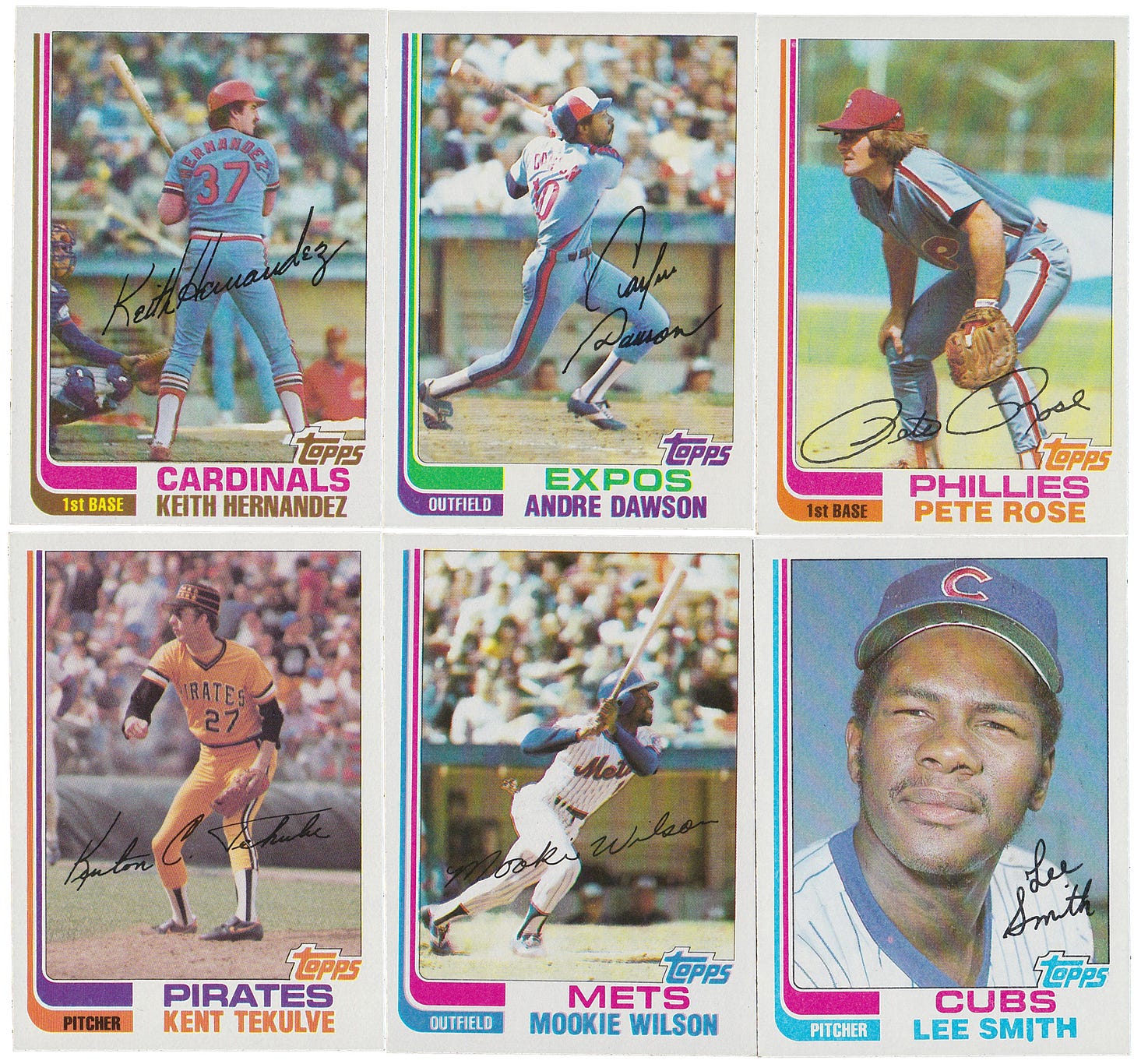

Cardinals: Keith Hernandez #210 This is not a great card, and it’s clearly inferior to Keith’s card from 1981, which was also my Cardinals pick, but there’s not much to choose from among the Cardinals in the 1982 set. This one gets the nod thanks to the depth of field, showing a jacketed coach in the Cardinals’ dugout, the on-deck hitter (overlapped by Hernandez), and the Mets’ catcher, the last providing a bit of foreshadowing of Hernandez’s future.

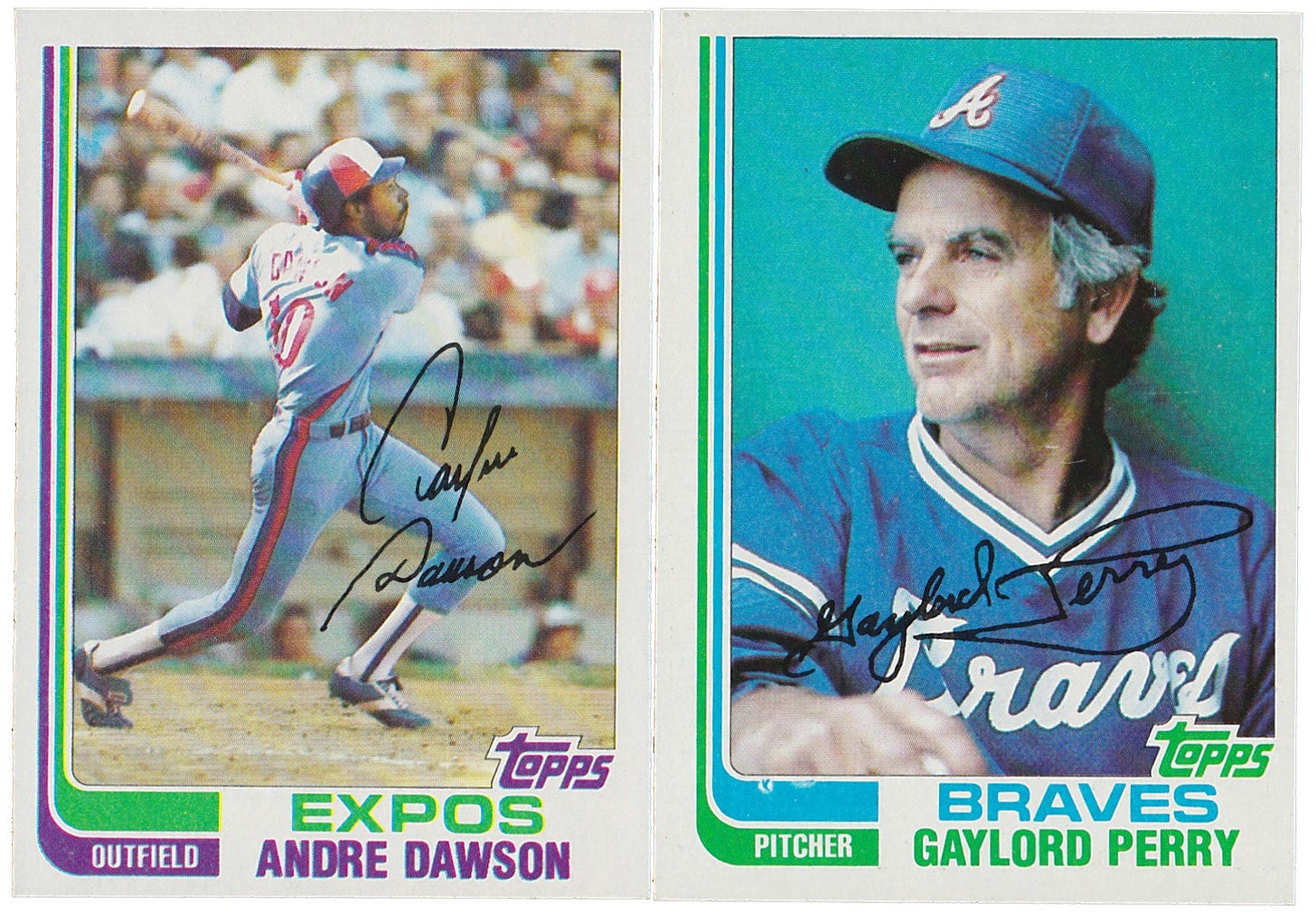

Expos: Andre Dawson #540 Dawson just edges out Tim Raines #70. The two cards are similar action shots from Shea Stadium. In fact, three of the six cards in this division, plus one in the NL West, are all taken from the same spot at Shea, and many of the best cards in this set are of right-handed batters at the plate taken from that first-base photographer’s box, be it at Shea Stadium, Yankee Stadium, or, in a twist, the Oakland Coliseum. The Dawson card is just more dynamic than the Raines, and Dawson is captured in a position that is more distinctly characteristic of his swing. Dawson also had one of the more creative signatures of the era, which is well-placed on this card.

Phillies: Pete Rose #780 Somewhere in my mom’s basement is a spiral notebook in which I imitated the signatures of probably about a couple dozen star players from the 1970s and early ’80s by imitating their signatures from their baseball cards. The only one I can still do from memory is Pete Rose, who very likely has signed more autographs than any ballplayer in history. His big, bubbly signature fits right in on this card, echoing the rounded P on his jersey, his fingerless first-baseman’s mitt, and his signature shaggy bowl cut. Rose was not an attractive man, but you could almost be convinced he was by this card. I’m not sure bowl-cut-era Rose every looked better on a baseball card.

Pirates: Kent Tekulve #485 There wasn’t much to pick from among the Pirates in this set either, but you can’t go wrong with bumble-bee-era Kent Tekulve, with his shades, all the Stargell stars on his cap, and that scrawny, side-arm delivery. Bonus points for the well-placed full-name signature “Kenton C. Tekulve.”

Mets: Mookie Wilson #143 Mookie’s first solo card almost didn’t make the cut here. It’s a great image, but the photo is out of focus and both my card and every one I could find online has a similar printing error in which the colors don’t line up, which makes it look even blurrier. That printing error wasn’t uncommon on vintage Topps cards, but usually you can find a crisp one if you look hard enough. I’m not sure that’s true for this Mookie Card. Still, that pose is so great and fits so well within the frame, I had to include it.

Cubs: Lee Smith #452 Smith’s rookie card is a handsome Spring Training portrait of the future Hall of Famer. He has the strong-chinned, narrowed-eyed look of a ship captain or super hero standing tall in preparation for an adventure ahead, an appropriate introduction for the future (and now former) all-time saves leader.

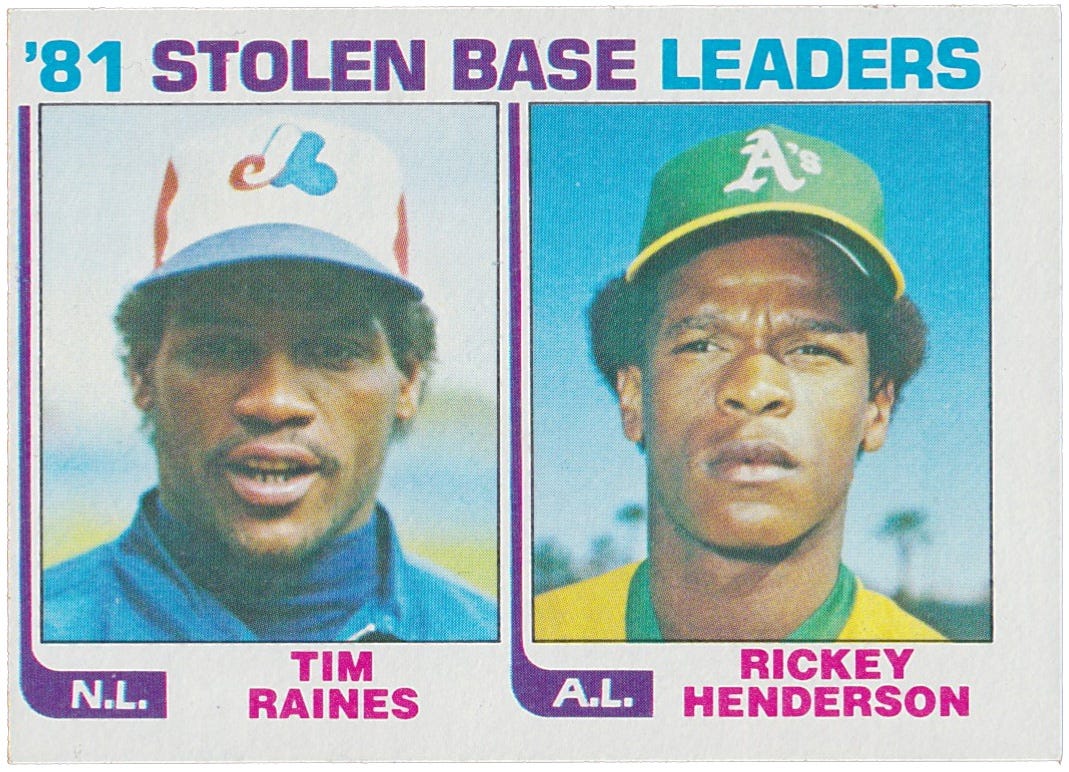

Wild Card: ’81 Stolen Base Leaders #164 From 1982 to 1984, Rickey Henderson and Tim Raines, the two greatest basestealers in major-league history, shared a Stolen Base Leaders card in the flagship Topps set. This is my favorite of the three, even though the 1983 card has Rickey’s record 130 steals on the back and the 1984 card has both players at or above 90 steals. Rickey stole just 56 in 1981 due to the shortened season, but Raines stole 71 in just 88 games, which over a 162 games pro-rates to . . . 131. Not bad for a rookie. Bonus points to Topps for getting the apostrophe pointing in the right direction.

National League West

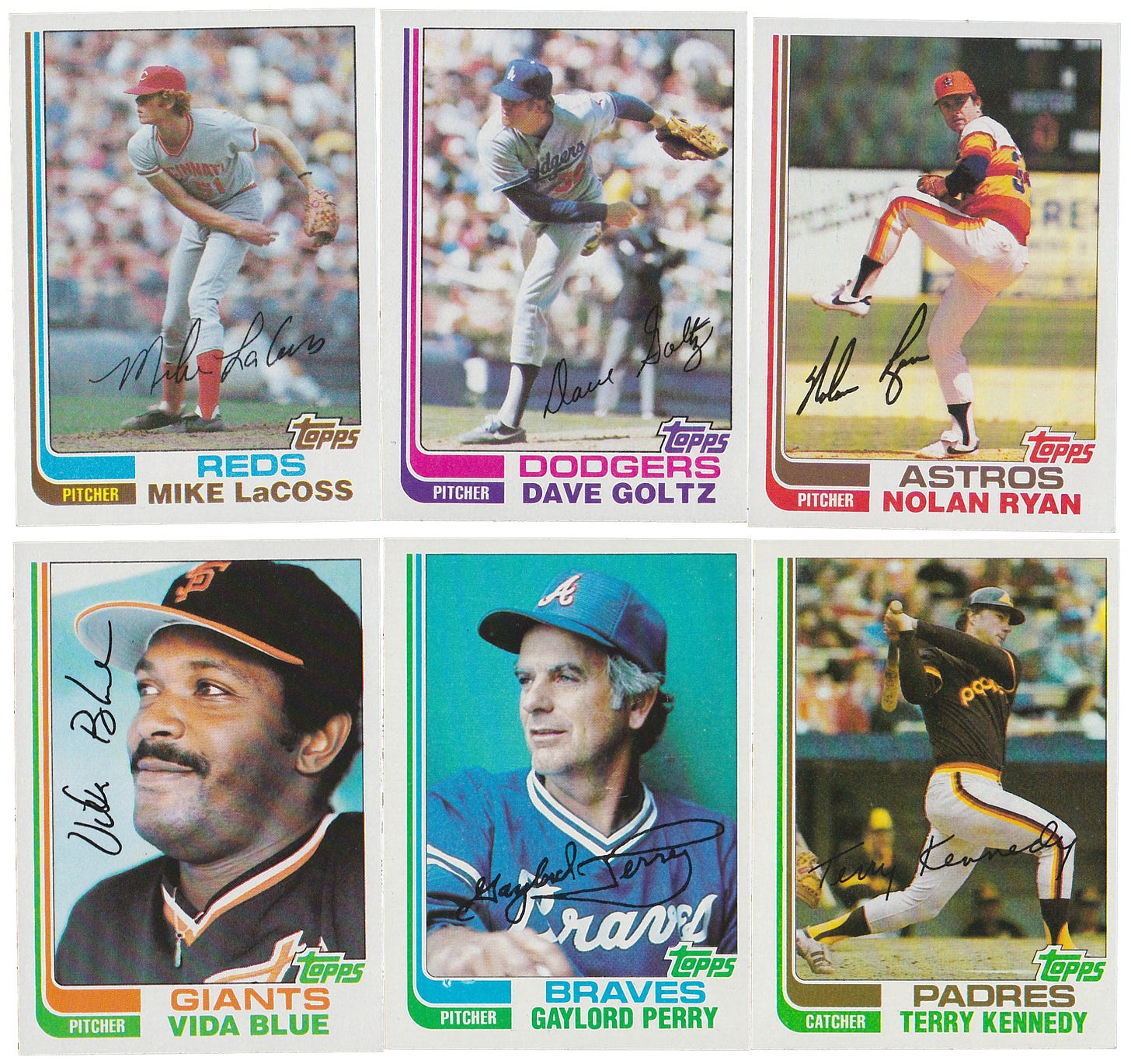

Reds: Mike LaCoss #294 Mario Soto #63 is a great hat-back, squinty-face card of a pitcher who was briefly one of the best n the game, but I like this Mike LaCoss card, which shows the black shoes and low stirrups all Reds players were required to wear in those days.

Dodgers: Dave Goltz #674 The Dodgers wore two distinct left-sleeve patches in 1980 and 1981. The 1980 patch was a circular one celebrating that year’s All-Star Game at Dodger Stadium (best seen on Dave Goltz’s 1981 card, #548). The 1981 patch was key-shaped and celebrated Los Angeles’s bicentennial (it’s effectively of a stick figure with raised arms and a rainbow arching between them, not seen clearly on any card, but best on Dusty Baker’s #375). Those patches let you know when the photos on the 1982 Dodgers cards were taken, and surprising number were taken in 1980 or even before (see the lack of patch on Reggie Smith In Action #546). I disqualified the photos from 1980 from the competition here, which left me with few compelling options, thus the choice of the Goltz, a nice action shot framed nicely with a well-placed signature and the depth-of-field to include the third-base umpire.

Astros: Nolan Ryan #90 This card could be better. I don’t like the Spring Training background. The dirt and grass are both an odd color that makes the card look a little sickly. Still, the Topps cards of Nolan Ryan on the Astros are dominated by close-ups and practice jerseys. Outside of the inferior Highlights card in this set (#5: Nolan Ryan Pitches 5th Career No-Hitter), this is the only regular-issue Topps card of Ryan in action in his tequila-sunrise Astros jersey.

Giants: Vida Blue #430 With not much to pick from on the Giants, I couldn’t resist the comedy of this card, which makes it look like Blue is interacting with his signature, holding in a laugh while the autograph buzzes around his face a bug or an over-excited puppy.

Braves: Gaylord Perry #115 Gaylord Perry was not an attractive man, particularly at this late stage of his career. The 42-year-old righty was overweight, bald, greying, and had a sagging neck. On this card, however, he’s a full-on silver fox. This might be the most handsome Perry ever looked in a photograph in his entire life, and the flourish on his signature adds to his dashing look. It’s such a good photo you don’t even notice the mesh front of the Braves’ batting practice cap.

Padres: Terry Kennedy #65 There’s nothing terribly special about this Terry Kennedy card relative to the other Padres photos taken from this angle, and the coloring is a little sickly (not helped by all the green on the border), but I like the full-extension of his two-handed follow-through, so it gets the nod here.

American League East

Brewers: Bob McClure #487 A handsome portrait with a nice, crisp photograph, a rarity for this set.

Orioles: Doug DeCinces #564 This isn’t the only card depicting a player signing an autograph in this set, but it’s my favorite of that small subset. I like the tipped-back cap and the fact that what DeCinces is about to write on that kid’s program is printed over his photo on this card.

Tigers: Alan Trammell #475 This is the closest this set gets to the 1981 Robin Yount card. Here’s future Hall of Famer Trammell, hanging out, bat-in-hand, having a laugh during batting practice. Bonus points for the home uniform and depth of field.

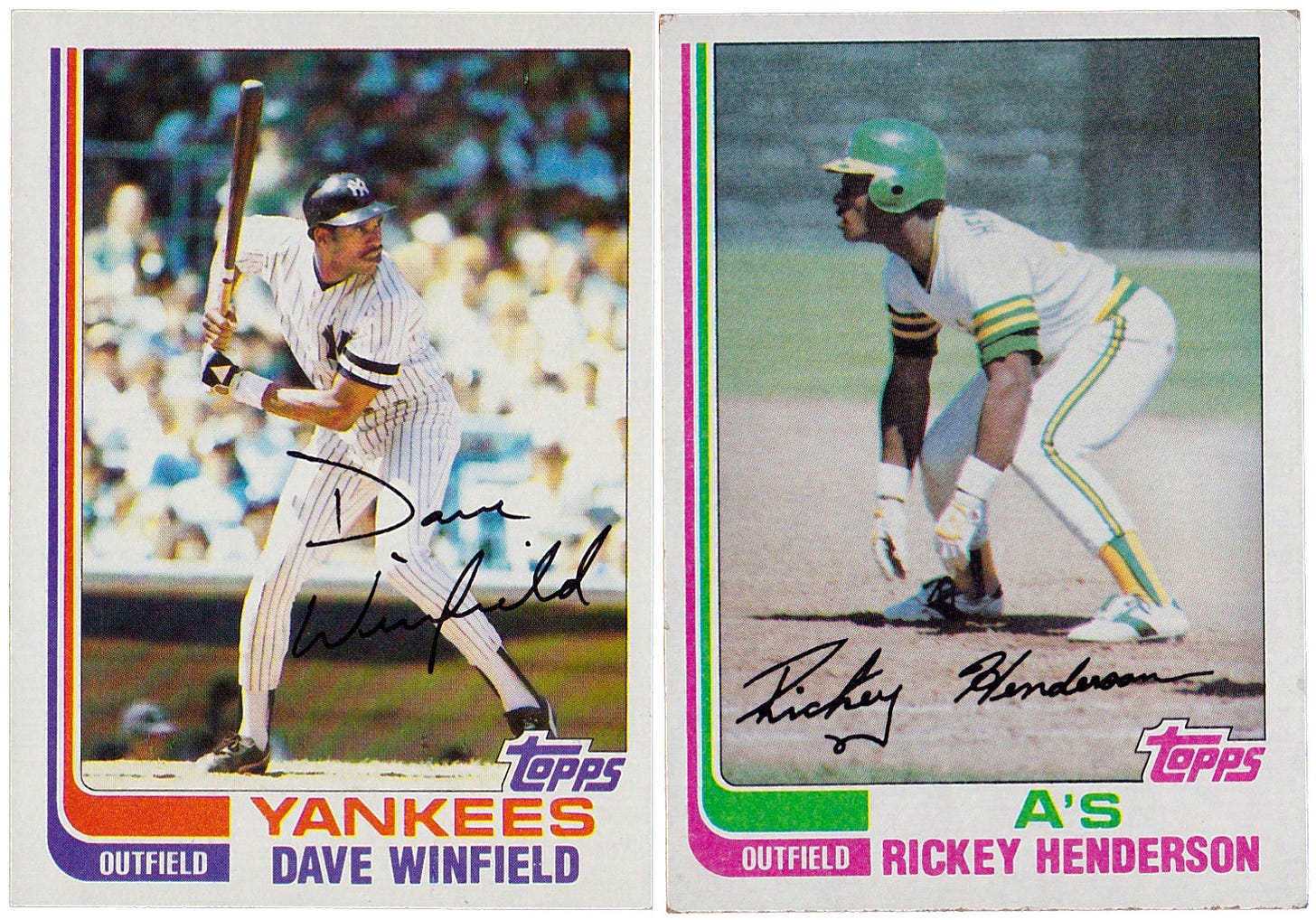

Yankees: Dave Winfield #600 Winfield’s first flagship Topps card as a Yankee may be his best in that uniform. What raises it above the level of other cards of Winfield at-bat taken from that angle is both the clarity of the photograph and the fact that he has already started his swing. Winfield had a hitch in his swing, and you can see that he has lifted his front foot and dropped his hands, he’s coiled and ready to unleash that monstrous whip, which often sent his bat flying. The autograph is well placed. The sun is bright. This is a card that makes you wish you were at that game.

Red Sox: Reid Nichols #124 A sharp portrait in a home uniform in the Fenway dugout with some depth (note the stirrup-socked leg in the background, behind a pole), all complimented by the fact that the Red Sox actually got their team colors in the border in this set. Nichols, still a rookie in 1982, hit .293/.347/.449 (112 OPS+) in 572 plate appearances as a utility outfielder for the Sox in 1982 and ’83, but quickly washed out after that.

Cleveland: Dave Rosello #724 Great lighting and an incredibly crisp photo. In this set, that was enough. Rosello, incidentally, was a Puerto Rican utility infielder and failed Cubs prospect who had already played his last major-league game by the time this card came out. He spent 1982, his age-32 season in Triple-A, then retired.

Blue Jays: Roy Lee Jackson #71 Jackson escaped the Mets and had a breakout season as a 27-year-old reliever in 1981, but he still looks a bit troubled here. This is such a unique pose for a baseball card, I’m quite fond of it. Add the tipped-back cap, flourishes in the signature, and crisp photography, and it’s another easy winner in an ugly set.

American League West

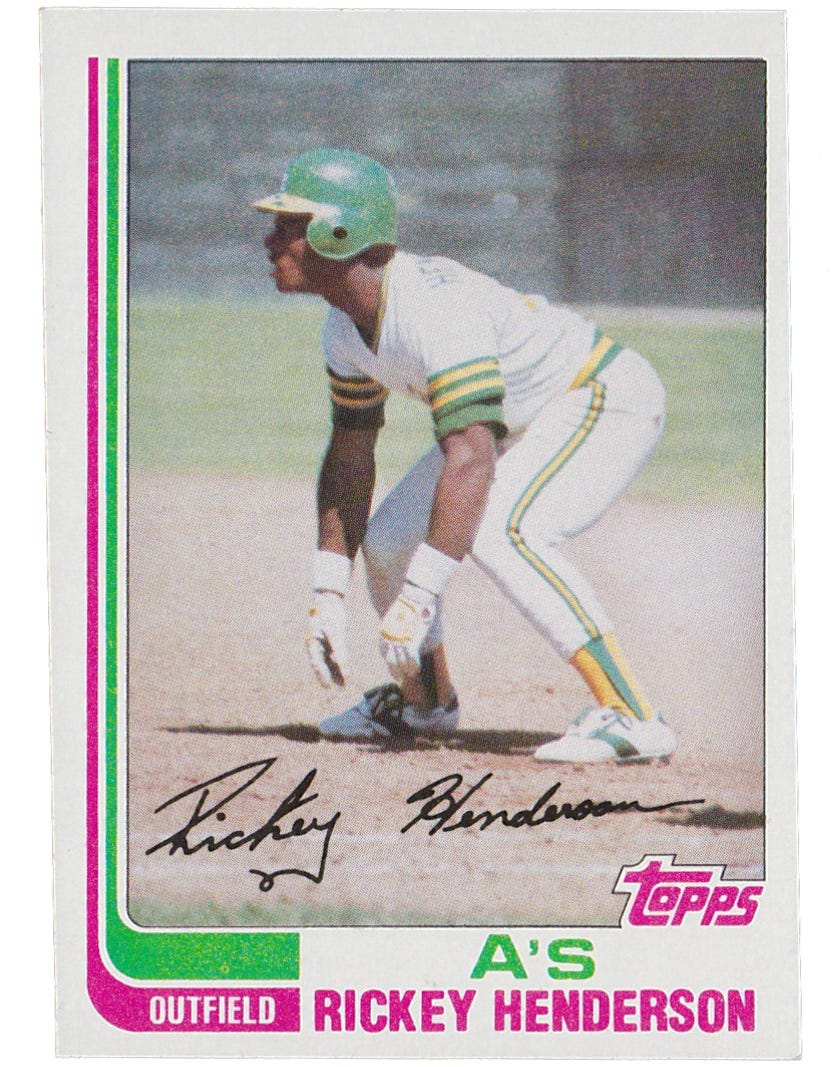

A’s: Rickey Henderson #610 Iconic. The best basestealer in major-league history poised in the basepath, underlined by his sharp signature, back when the A’s still wore Kelly green. This was the card kids held in their hands while they watched Rickey steal 130 bases in 1982.

Rangers: Pat Putnam #149 Pat Putnam again? It appears so. I like the parallel lines in this card, his bat, his signature, his eyeline and that of the kid crouching near the wall behind him. Did Pat get all of it? Unlikely. He only hit eight home runs in 1981, and I think this photo was taken in Oakland.

White Sox: Chet Lemon #493 This one was definitely taken in Oakland, note the A’s cap o the guy below Lemon’s leg. This is a real beauty. Those White Sox uniforms were awful, but you wouldn’t know it from this picture. The blue tops hide the butterfly collar, Lemon’s leg kick hides that his jersey is untucked, and he is showing every one of the stripes on his socks, which were the best feature of that uniform. As with Winfield, this card is elevated by catching Lemon mid-swing, ready to uncoil. It’s a nice, crisp, well-framed photo, and it gets bonus points for the full-name signature: “Chester Earl Lemon.”

Royals: Hal McRae #625 It’s a bit too green, but I’m a softy for seeing the Royals in their home uniforms on Topps cards (which is surprisingly common in this set), and McRae appears to be mid-hop in the basepath, suggesting action that is about to happen.

Angels: Brian Downing #158 I almost went with Mike Witt #744, a crisp portrait on a rookie card, but Witt looks like a teenager (he nearly was) and the blue sky is his only backdrop. Instead, let’s go with Downing’s muscles and dimples and the trees that give this card some depth (but not that ugly light stanchion behind his shoulder). Downing arrived as a power hitter in 1982, slugging 28 home runs, more than doubling his previous high. Looking at this card, few were left to wonder why.

Mariners: Gary Gray #523 Gray had just two Topps cards, and his 1983 stacked his name, making it look like an optical illusion. I don’t know if there has ever been another major-league player who had the same letters in his first and last name but in a different order (someone ask David Firstman), but I can’t imagine there has. Gray gets the nod here in part because of his name (and signature, which makes it look like he wrote the same name twice), but also because this is one of just two in-action shots of a Mariners player in this entire set and the portraits are all sub-par. Fun fact: Gray’s middle name was George, so his initials were GGG.

Twins: Danny Goodwin #123 Crisp photo, cool lighting, unique angle, absolute beast of a mustache. Goodwin made his last Topps card count. I don’t even mind that you can’t see the end of his signature.

National League Championship

Perry was a pretty easy pick from the West, but I had a hard time in the East between Dawson, Pete Rose, Mookie Wilson, and the Stolen Base Leaders. I eliminated Mookie because he was blurry, Pete because he was stagnant, and the Stolen Base Leaders because I was judging that more on collectability than aesthetics. That left me with Dawson, who edges Perry pretty easily, because actual game action is always going to beat a portrait of a guy in Spring Training duds against a plain background, no matter how deceptively handsome he may appear.

NL Champion: Andre Dawson #540

American League Championship

I noticed in the process of doing this that I have two of the Henderson card, but the one in my 1982 album is miscut (that’s the one seen in the AL West section above), and this one is slightly faded and dinged. I should get a third that’s in better shape.

These were two of my favorite players growing up as a Yankee fan in the late ’80s, so maybe I’m not being as objective as I think, but I love both of these cards and have for decades. The lighting on the Winfield may actually give it the edge on pure aesthetics, which is how I purport to be judging these cards, but the Henderson is so unique, both in terms of the action captured and who it has captured and when, that, when you factor in the perfection of the framing and the signature placement, it just barely edges out the win.

AL Champion: Rickey Henderson #610

World Series

Seeing these cards together confirms that I have made the right choices. You can just see this game action. Dawson crushes a pitch to deep left center. Henderson breaks from first, racing around to score. That’s baseball. Portraits of players are nice, but cards that evoke the action of the game are even better. But which is the best card in the 1982 set? The Dawson is more kinetic, has great depth of field and uniform details, including all of the colors of the Expos’ pinwheel helmets, Dawson’s name and number visible on his jersey, and his racing stripes lined up perfectly at the waist. Both players are Hall of Famers. Both border designs clash with the team colors.

I just can’t get past how iconic that Rickey card is. Most players, when they take their lead, hold their hands above their knees. Rickey was unique in getting into a deep squat, dangling his hands low, by his ankles, and wiggling his fingers. For opposing pitchers and catchers, this was a very threatening, even intimidating stance, and here it is, perfectly framed by the card and his signature. He’s about to break for second, and about to shatter the single-season stolen base record, and a whole lot more after that. This is one of the game’s greatest players on the precipice of establishing his greatness, crouched and ready to explode in the basepath and onto the league. It is a great card, the best one in this set, and an early contender for best of the decade.

Champion

#610 Rickey Henderson

I need to get one that’s both straight and sharp.

Feedback

I want to hear from you. Got a question, a comment, a request? What would you like to read about in lieu of actual baseball news? Reply to this issue. Want to interview me on your podcast, send me your book, bake me some cookies? Reply to this issue. I will respond, and if I find your question particularly interesting, I’ll feature it in a future issue.

You can also write me at cyclenewsletter[at]substack[dot]com, or @ me on twitter @CliffCorcoran.

Closing Credits

The biggest hit of 1981, in fact of the entire 1980s, according to Billboard, was “Phyiscal” by Olivia Newton-John, a song about sex that went supernova by cashing in on the then-current aerobics trend and the new music-video channel that launched less than two months before the song’s late-September release (there was significant debate on my first-grade playground about just what Oliva meant by “physical”).

Richard Simmons and Jane Fonda were in the process of building their exercise empires at the time, and the video for “Physical,” an early MTV staple that won the second- and final-ever Grammy for Best Video, depicted Newton-John working out in her soon-to-be iconic headband. Having made the transition from her virginal 1970s persona to her sexier 1980s persona seemingly on screen in Grease in 1978, Newton-John is sweat-drenched and dressed in skin-tight spandex in bold, 1980s colors. Joining her on the extremely ’80s gym set are, alternately, a series of ultra-buff male models in Speedos and a group of comically out-of-shape men in gym shorts and tank tops. When the guitar solo arrives, the out-of-shape dudes transform into the models, who then, in a surprisingly progressive twist, leave the gym with their arms around one another, leaving Oliva behind to initiate a tennis date with one of the heavy-set guys. It’s a classic, and you’ve seen it.

I was going to end with that video, pointing out that we should have been watching the players get physical this week with the initial batch of calisthenics that follows the arrival of pitchers and catchers at camp, but I had a different musical experience this week that I wanted to share.

Ronnie Spector, formerly of the mid-’60s girl group the Ronettes, died of cancer on January 12. Spector—who was born Veronica Bennett but married her producer, the psychopath, genius and future murderer Phil Spector, in the late 1960s—lived a life that was alternately a dream and a nightmare. When Ronnie died, Caryn Rose, a music journalist friend of Jay Jaffe’s, recommended Ronnie’s 1990 autobiography Be My Baby and, having always loved Ronnie’s voice and stage persona, I leapt at the suggestion.

As it turns out, the book is currently out of print (I got it out of the library), but will be reissued later this year and is reportedly being adapted for the screen with Zendaya in the starring role. Reading it, I was amazed it took this long to be made into a movie. It reads like a biopic to such a degree that it’s almost difficult to believe it’s all true (not that I doubt any of Ronnie’s allegations about Spector’s years of emotional and psychological abuse). Zendaya might be a little tall to play the petite powerhouse, but she’s otherwise perfect for the part (in addition to her strong screen presence and experience as a pop singer, she and Ronnie are both biracial, a fact Ronnie mentions in the first line of her book). I hope it happens, though I don’t much look forward to sitting through the more painful parts of Ronnie’s life having already experienced them in print. In the meantime, I recommend the book, which is a genuinely dishy roller-coaster ride, a cautionary tale about falling in love with an abuser, and an important account of the ways in which the damage done by such a relationship long outlasts the relationship itself.

One thing that struck me in reading the book, beyond the highs and lows of Ronnie’s life, was her love of performing. Ronnie was one of those kids who sang into a hairbrush to an imaginary audience, and those fantasies became reality in short order. Phil Spector kept her from performing (or doing much else) for most of their marriage, but she never lost that joy of being on stage, and rushed back out to perform almost immediately after escaping Spector.

Ronnie’s descriptions of the Ronettes’ 1960s performances, in which she did whatever she could to whip the crowd into a frenzy, sent me to YouTube to try to find a representative performance from the group’s heyday. I didn’t find the sweaty revue performances she describes, but I did find the group’s performance from the Big T.N.T. Show, a sequel to the legendary T.A.M.I Show, at the Moulin Rouge in Los Angeles in 1966.

The Ronettes are very clearly singing live here (they do “Be My Baby,” of course, and the Isley Brothers’ “Shout”), and Ronnie sounds as good as she does on any of the group’s recordings. You can see her desire to interact with the audience (though she is restrained slightly by the large stage and the length of her mic cord), and she teases them with a bit of rump shaking that toed the line for a filmed performance in the United States in 1966. This may not be as raw as the group’s touring performances, but the joy that Ronnie wrote about is plainly evident, and I wanted to share it.

The Cycle will return next week, though the three-day weekend may prompt me to push my look at the 1983 Topps set to the week after. We’ll see how much comes out of the promised labor negotiations. Fingers crossed. For those of you who get a three-day weekend, enjoy it.

Until then:

I easily would've picked the Nolan Ryan over Gaylord Perry out of the NL West, even if Nolan's in spring training. Perry, to me, looks like he's in an aquarium, with all that blue and green on the card making it look tinted. And as you said, a baseball card shot of Ryan in that tequila sunrise jersey is a rarity and so enjoyable to look at. I can't argue with Winfield over Ryan for the AL championship, but give me the sunshine on the Ryan card over the blues of the Perry.