The Cycle, Issue 119: Denial, Anger, Bargaining

Placing the current labor negotiations in historical context, identifying the best 1981 Topps card, the MLB news you need to know, and my latest podcast appearance.

Table of Contents

In this issue of The Cycle: Thoughts on the contents of this issue and introducing a new section (or two)

What You Need To Know: Labor update and some stuff that’s even more depressing

Labor Pains: Figuring out how we got here via a look at the previous dozen Collective Bargaining Agreements

Pop of the Topps: Finding the best Topps card of 1981

Shameless Self-Promotion: The Infinite Inning, Episode 214

Feedback

Closing Credits

In this issue of The Cycle . . .

With nothing concrete happening on the labor front over the last week in the wake of the owner’s federal-mediation gambit (which the players rejected, as expected, last Friday), I wanted to take the opportunity to firm up my, and your, understanding of the history of collective bargaining in Major League Baseball. Specifically, I wanted to make a thumbnail sketch of all of the previous Collective Bargaining Agreements and their most significant components, with a particular focus on the recent history of how we got to where we are.

After appearing on The Infinite Inning with my old pal Steven Goldman earlier this week, I felt that desire even more acutely, as I spoke at length about that history on that episode of Steve’s podcast and realized after the fact that, while my points all hold up just fine, generally, things got a little shaky when I got into specifics, particularly with regard to some dollar amounts and their relationship to the cost of living. With the time to do so, I get those things right below.

I’m keeping this introduction bit around for now and adding a new section this week called “What You Need to Know,” which is sort of an abbreviated version of my old “Newswire” section, that keeps you in the loop on the top stories while only skimming the surface. As I’ve mentioned many times at this point, I get to add my two cents on the news at is happens via the free, daily MLBTR Newsletter, and when and where I want do dig deeper, I will do so, but I need to try to keep these issues to a reasonable length (ha! more than 7,500 words this week), so I just can’t say everything I have to say about everything in every issue. As always, if you want more from me on a certain topic, please reply to this issue or drop me an email or a tweet (see Feedback below) and I’ll either respond directly or in a subsequent issue.

Given that the news this week is all pretty bleak, and I know a good many of you would prefer not to get an issue all about the game’s collective bargaining history, I want to give you a little sugar to help the medicine go down. As Cyclist Tim suggested last week, “If the options are more coverage of the owners (barely) bargaining in bad faith . . . or . . . Go with the ‘or’ . . . anything that reminds us baseball is fun.” I heard that one loud and clear, so, as if often my goal with The Cycle, you can choose your own adventure: brush up with a history lesson on baseball’s labor relations, use the WYN2K section as a prompt to read more elsewhere about those top stories, or scroll past the vegetables and get straight to desert with my attempt to identify the best baseball card in Topps’ 1981 flagship set.

What You Need To Know

Collective Bargaining to Resume Saturday: The owners had some pre-scheduled meetings in Orlando this week, while the players met in Arizona. Commissioner Rob Manfred held a press conference on Thursday in which he confirmed reports that the owners will make their next proposal to the players on Saturday. He also said that he is not yet announcing the delay of major-league Spring Training (one presumes so that he can blame the players for the delay when they don’t instantly accept the owners’ offer on Saturday), told some lies about the owners’ past proposals and the profitability of owning a major-league team, and generally worked to project optimism about Saturday’s proposal, of which I remain highly suspicious, particularly given the things he said about the owners’ past proposals. As expected, the players rejected the owners’ request for federal mediation last Friday. The last offer by either side remains the players’ proposal from February 1.

Los Angeles County’s District Attorney Will Not Bring Criminal Charges against Trevor Bauer: Here’s the DA’s statement: “After a thorough review of the available evidence, including the civil restraining order proceedings, witness statements and the physical evidence, the People are unable to prove the relevant charges beyond a reasonable doubt.” Bauer responded by denying all of the alleged victim’s claims, for the first time, via a video on Twitter. MLB’s investigation into Bauer’s actions remains ongoing, thus the league and the Dodgers offered no comment.

The Trial of Eric Kay, Concerning Tyler Skaggs’ Death, is Underway: Kay is the former Angels communications director who is charged with “conspiracy to possess with intent to distribute a controlled substance resulting in death and serious bodily injury” related to the July 1, 2019 overdose-related death of Angels pitcher Tyler Skaggs. Skaggs’ mother and former Angels teammate Andrew Heaney have already taken the stand, while Kay’s defense team said in its opening statement that it intends to implicate another of Skaggs’ former rotation-mates, Matt Harvey, in Skaggs’ acquisition of the drugs on which he overdosed. Skaggs had alcohol, fentanyl, and oxycodone in his system when he died, but a forensic pathologist who examined Skaggs has testified that he can’t be 100-percent certain that the drugs are what killed Skaggs.

The Rockies Have Overhauled Their Analytics Department: Any movement of this kind from the Rockies is newsworthy, even if the person the Rockies have put in charge of their expanded research and development department, Scott Van Lenten, came from the Nationals, another organization that is behind the curve in this area. The Rockies also hired a data architect away from the Rays, an analyst away from the Twins, an R&D executive away from the Dodgers, a data engineer who used to work for the South Korean government, and a web developer charged with creating an in-house system to distribute information to players, coaches, and staffers. They have also promoted and/or hired several women, two in their scouting department and one to work on roster, contract, and arbitration issues. All of those are shockingly progressive moves from the major-leagues most regressive organization.

Also:

The Rockies Extended Manager Bud Black Through 2023

Former All-Star 1B Adrián González Officially Retired

Former OF Gerald Williams died of cancer at age 55 on Tuesday.

Former OF/1B Jeremy Giambi died of suicide at age 47 on Wednesday.

Labor Pains

How We Got Here: A Quick History of the CBA

Since MLB Players Association Executive Director Marvin Miller brought collective bargaining to baseball in the mid-1960s, there have been twelve Collective Bargaining Agreements. The first was in 1968, and since the players were starting from a such a low point, the CBAs of the late ’60s and 1970s were almost entirely positive for the players.

Things got a little shakier in the 1980s, with Donald Feher succeeding Miller as executive director in December 1983. Michael Weiner succeeded Feher in 2009 but oversaw just one CBA before dying of a brain tumor in November 2013, sending the Players Association reeling. Former first baseman Tony Clark succeeded Weiner, led the union through the last CBA in 2016, and remains the executive director, but the union has since hired hard-nosed attorney Bruce Meyer as a lead negotiator, hoping to recover some of their losses from recent years.

What are those losses and when exactly did they occur? I’m hoping the following thumbnail sketch of the first twelve CBAs will help you sort that out, though I have some more commentary below to explain some of it.

For further reading, check out the far more detailed summaries of these agreements, and some of the collectively bargained agreements that fell between proper CBAs, over at Cot’s Baseball Contracts, the timeline on the MLBPA’s website, this piece on the remarkable first decade of Miller’s tenure that I wrote for The Athletic in 2018, Miller’s autobiography A Whole Different Ball Game (published in 1991), John Heylar’s Lords of the Realm (published prior to the 1994 strike), and Howard Bryant’s Juicing the Game, which picks up the thread with the ’94 strike and was published in 2005 (and which I edited).

1968: CBA #1

Ratified: Feb. 28

Notable changes: Establishes collective bargaining as the means for altering rules governing player contracts and compensation. Introduces a revised standard player contract. Establishes a grievance procedure, with the commissioner as the final arbiter. Establishes severance pay for players released mid-season. Establishes a maximum pay cut. Increases minimum salary by 67 percent, also increases allowances during Spring Training and the regular season. Establishes rules for improved travel conditions and scheduling restrictions regarding double-headers and off-days.

1970: CBA #2

Ratified: May 23

Notable Changes: Establishes independent arbitration for player grievances (a crucial step that will ultimately make free agency possible). Establishes players’ right to use agents in salary negotiations. Establishes a deadline for unsigned players to be tendered contracts. Establishes severance pay for payers cut during Spring Training. Increases in minimum salary, severance pay, and player share of playoff pool, plus additional improvements to travel conditions.

1973: CBA #3

Ratified: Feb. 28 (after 17-day lockout)

Notable Changes: Establishes salary arbitration for players with at least two years of service time. Establishes that players with five years of service time can reject minor-league assignments. Establishes 5-and-10 rule allowing players with 10 years of service time, the last five with the same team, to block trades. Folds pension plan into the CBA for the first time (dispute over pension compensation had resulted in the first player strike in April 1972, cancelling 86 games). Moves tender deadline to Dec. 20. Increases in minimum salary, Spring Training allowances, playoff shares.

1976: CBA #4

Ratified: July 12 (after 17-day lockout in Spring Training, the season opened on time but without a new CBA in place)

Notable Changes: Free agency is codified in the wake of the December 23, 1975, arbitration ruling by Peter Seitz that asserted that the reserve clause did not entitle teams to perpetual control over players. Establishes that players must have six years of service time to become free agents. Establishes free-agent re-entry draft, which limits the number of teams a player can negotiate with and the number of players a team can negotiate with. Establishes draft-pick compensation for teams that lose players to free agency. Establishes that players with at least five years of service time may demand a trade. Increase to minimum salary and pension contributions.

1980: CBA #5

Ratified: July 7 (after eight-day Spring Training strike)

Notable Changes: Establishes a committee to study free-agent compensation, that the committee’s recommendations can be bilaterally adopted as part of the CBA in early 1981, that the owners can unilaterally impose their own changes if the players don’t agree to the committee’s recommendations, and that the players can re-open the CBA and strike if they object. Guess what happened?

1981: CBA #5.1

Ratified: August 2 (after 50-day strike that bifurcated the 1981 season)

Notable Changes: Establishes professional-player compensation for free agents. Creates Type-A and Type-B free-agent classes for purposes of free-agent compensation. Teams losing Type-A free agents receive one amateur draft pick and also get to select a professional player from another organization via an established player pool. Teams losing a Type-B free agent get two draft picks. All other free-agents result in a single draft-pick as compensation. Players receive service time for duration of strike. Extends term of CBA and pension agreement by one year. Increases in minimum salary, pension contributions, and life-insurance coverage.

1985: CBA #6

Ratified: August 7 (after two-day strike, all games are made up)

Notable Changes: Eliminates free-agent re-entry draft; all players may negotiate with all teams, and vice versa, however if a team wants to retain its own free agent it must also offer him salary arbitration for the ensuing season. Increases service time required to reach salary arbitration to three years. Eliminates professional-player free-agent compensation. Expands League Championship Series to best-of-seven. Increases in minimum salary, pension contributions, World Series shares. Players are credited with service time for the two days of the strike.

1990: CBA #7

Ratified: March 18 (after 32-day lockout in Spring Training, which delays Opening Day)

Notable Changes: Establishes Super Two arbitration eligibility for top 17 percent of players with between two and three years of service time. Establishes that teams must offer their own free agents salary arbitration to receive draft-pick compensation if they sign elsewhere. Increases in minimum salary, pension contributions, adjustments to start of season to compensate for strike.

1995: CBA #7.1

Injunction: April 2 (after starting the 1994 season without an agreement in place, the players went on strike in August 1994; a federal injunction ordered the players back to work under terms of the old agreement on April 2, 1995)

Notable Changes: Extended terms of previous agreement through 1996 season, with increase in minimum salary for 1996. Some alterations to the 1995 season necessitated by the strike. Players are credited with service time for the strike, but 1995 salaries are pro-rated to the 144-game schedule. Union agrees not to take legal action against the owners for unfair labor practices.

1997: CBA #8

Ratified: March 14

Notable Changes: Establishes a luxury tax on the teams with the five highest payrolls for the 1997–99 seasons, only. Establishes revenue sharing among teams. Establishes interleague play. Increases in minimum salary and pension contributions.*

*Minimum salary and pension contribution increases are obviously standard for every CBA. The real issue is the degree of increase, which is more granular than I want to get in these capsules, so I’m going to stop mentioning them.

2002: CBA #9

Ratified: August 30 (averting a strike by hours, at most)

Notable Changes: Establishes new competitive-balance tax system on payrolls above a certain threshold and higher tax rates for repeat offenders, maxing out at a 40 percent tax on payroll above the threshold. Massive increase in revenue sharing. Tables contraction of teams for duration of agreement, but leaves door open to contraction at the end of the agreement. There was a lot more in this one, but those are the big items.

2006: CBA #10

Ratified: December 7

Notable Changes: Allows repeat offenders to to reset their competitive-balance-tax rates by spending a season below the threshold. Folds Joint Drug Agreement (established prior to 2003 season) into CBA. Eliminates restrictions on teams re-signing their own free agents between January 8 (if offered arbitration) and May 1. Eases free-agent compensation, eliminating compensation for Type-C free agents and awarding sandwich picks for Type-B free agents, rather than taking them away from the signing team; narrows definition of Type-A and Type-B free agents. Establishes August 15 signing deadline for amateur draft picks. Delays eligibility for Rule 5 draft by one year. Eliminates right of players traded during multi-year contracts to demand trades (save for some grandfathering). Owners agree to pay $12 million to settle claims of collusion following the 2002 and 2003 seasons, but do not admit guilt.

2011: CBA #11

Ratified: November 23

Notable Changes: Big changes to the amateur draft and international-signing rules. Establishes amateur draft signing-bonus pool (effectively hard slot caps), reduces draft by 10 rounds, bans major-league deals for draft picks (save multi-sport athletes), moves signing deadline up to mid-July, adds competitive-balance lottery picks after first two rounds. Establishes July 2 international signing period and signing-bonus pool amounts (spending limits which can be exceeded, triggering penalties); those restrictions apply to all international free agents except for players 23 and older from the top professional leagues in Japan, Korea, Taiwan, and Cuba.

Establishes qualifying-offer system of free-agent compensation. Increases Super Two eligibility to top 22 percent of players with between two and three years of service time. Increases CBT threshold just six percent from 2011 levels across entire, five-year CBA. Adds second wild-card team. Moves Astros to AL West for 2013 season. Expands rosters to 26 players for doubleheaders. Adds blood testing for human growth hormone to Joint Drug Agreement.

2016: CBA #12

Ratified: December 14

Notable Changes: Establishes additional tiers of penalties for exceeding the competitive-balance-tax threshold by certain amounts; increases the tax rate for exceeding the initial threshold for a third straight season to 50 percent; adds a draft-order penalty for exceeding the highest threshold.

Enforces a hard cap on international-signing-bonus pools. Raises age of professional players exempt from international-signing-bonus restrictions to 25. Increases offseason drug tests more than four-fold, ensuring every player on a 40-man roster is subject to at least one random test during the offseason; also increases number of in-season tests. Makes free agents who have previously received a qualifying offer ineligible for another. Reduces value of draft picks surrendered for signing a free agent who rejected a qualifying offer. Lengthens season to allow for four more off-days. Reduces minimum injured-list stay to 10 days from 15. Awards home-field advantage in the World Series to the team with the best record. Bans smokeless tobacco. Establishes anti-hazing/bullying policies.

The earliest concession the players are trying to claw back in these negotiations is the delay of arbitration eligibility from two years of service time to three, which Fehr surrendered in 1985 in exchange for the elimination of the free-agent re-entry draft and the use of professional players as free-agent compensation. The players have reclaimed 22 percent of that lost year via the Super Two rule, but it took them two different negotiations to get that (17 percent in 1990, when Fay Vincent was commissioner, and the other five percent in 2011). The players want the other 78 percent, while the owners want to get rid of the 22 percent.

The players also want to diminish revenue sharing as much as possible as they see it as a way to funnel revenues into the pockets of the owners least likely to spend them on salaries. Revenue sharing was introduced in 1997 and was massively expanded in 2002, both, again, under Fehr. It has been tweaked since, but the owners have thus far resisted any movement there, as well.

Another major point of contention for the players is the competitive-balance-tax threshold. A competitive-balance tax was first put in place in the 1997 CBA, but the current threshold system was introduced in the 2002 agreement. Again, those were Fehr’s negotiations, but it’s notable how the owners have slowly increased the incentives for teams to remain below the CBT threshold in the three CBAs since.

In 2006 (Fehr again), the owners added a carrot to the stick, rewarding repeat offenders for getting below the limit by allowing them to reset their tax rate. In 2011 (Weiner), they established a rate of increase in the threshold that barely exceeded the rate of inflation (as I will illustrate below). In 2016 (Clark), they greatly expanded the penalties for the league’s top spenders, increasing the top tax rate for repeat offenders to 50 percent, adding two higher thresholds with additional penalties so that the penalties got worse the more a team spent, and adding a draft-order penalty for exceeding the top threshold.

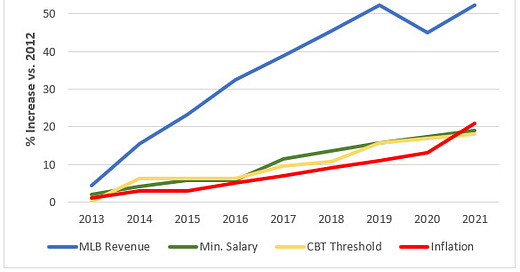

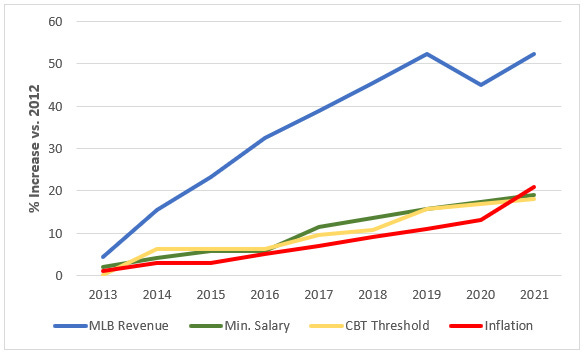

The rate of increase of the competitive-balance-tax threshold, as well as of the MLB minimum salary, is something that I think deserves a closer look. When I mentioned this on The Infinite Inning this week, my numbers were off, but my larger point was not. It amounts to the union losing ground by standing still.

While ownership has spent the last two CBAs dramatically restricting the pipelines of amateur talent coming into the game (for reasons I still don’t fully understand) by placing hard caps on draft-pick and international-signing bonus pools, the union, perhaps reasoning that those amateur players are not union members, has failed to extract much in return. Specifically, the union has failed to obtain increases in the league minimum salary and competitive-balance-tax thresholds that not only correspond to the overall growth in league-wide revenues, but that even manage to out-pace the annual increase in the cost of living.

Below is a graph that makes this quite clear. Using the figures from 2012 (the first year of the 11th CBA) as a baseline, the lines below chart the percentage of growth (again, relative to 2012) of the four things I just mentioned: MLB revenues (via Statistica.com), the MLB minimum salary, the CBT threshold (salaries and thresholds per the terms of the last two CBAs), and inflation (represented here by the increases in the consumer price index).

A quick note on the last two years, which are a bit funky due to the pandemic. The terms of the last CBA were set assuming a 162-game season. Actual salaries for 2020 were pro-rated down to the 60-games played, but, to keep everything on an equal scale, I’ve used the 162-game figures from the CBA here and prorated MLB’s 2020 revenues up to 162 games. I have not seen an official figure for 2021’s league-wide revenues, but anecdotal evidence derived from the financial disclosures of the publicly held company that owns the Atlanta Braves indicated that the league largely recovered from 2020’s dip in 2021. To represent that, I’ve simply reused 2019’s revenue figure for 2021, just to give the line the right shape. The actual number is irrelevant, really, because the point is just to show how far removed it is from those other three lines. I mean, look at this:

In essence, the blue line is the rate of growth of the owners’ revenues, while the green and red lines are the rate of growth of the players’ salaries. This is why the players are furious and finally taking a stand. It is also the primary reason that the last two CBAs are considered such disasters for the union.

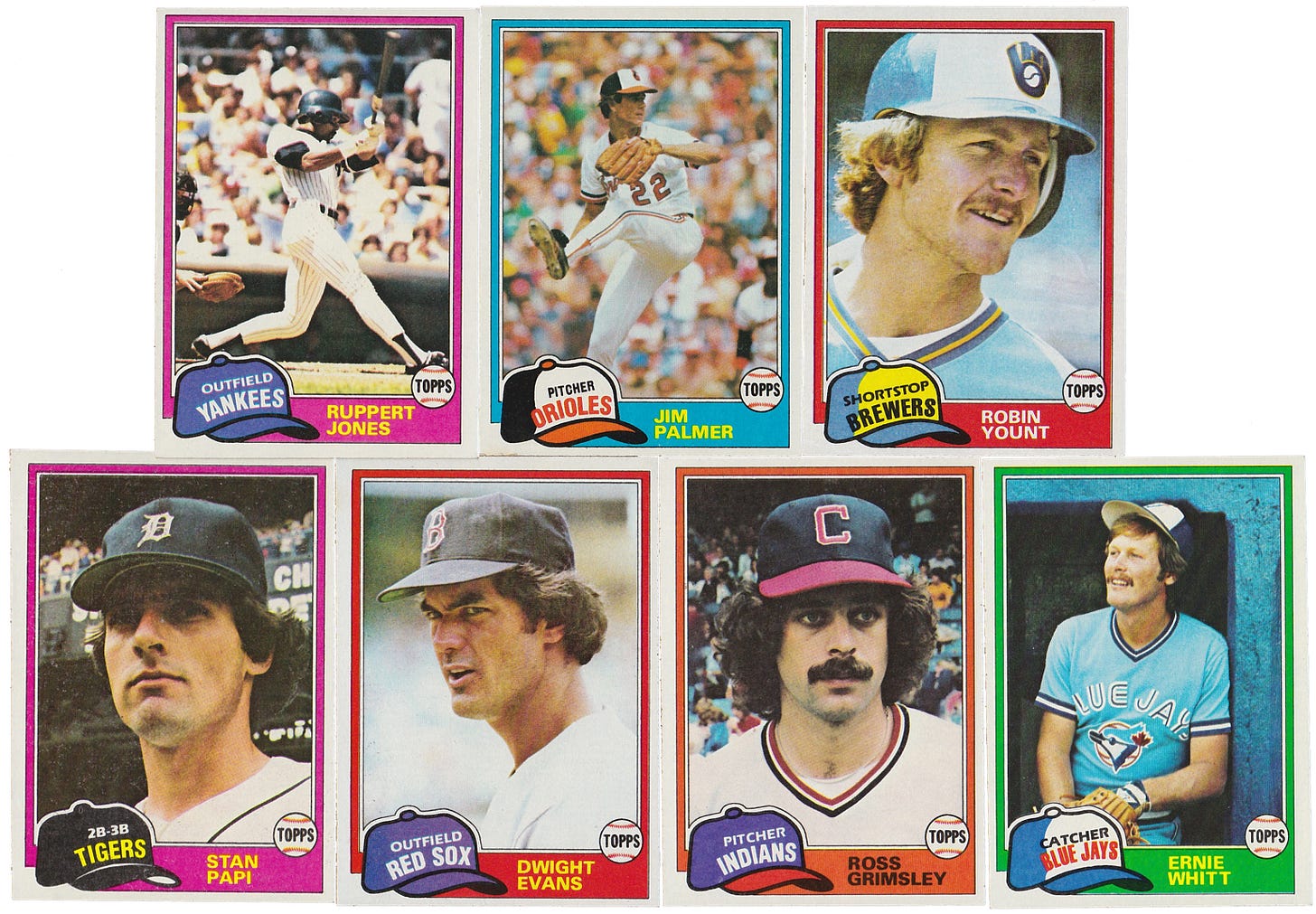

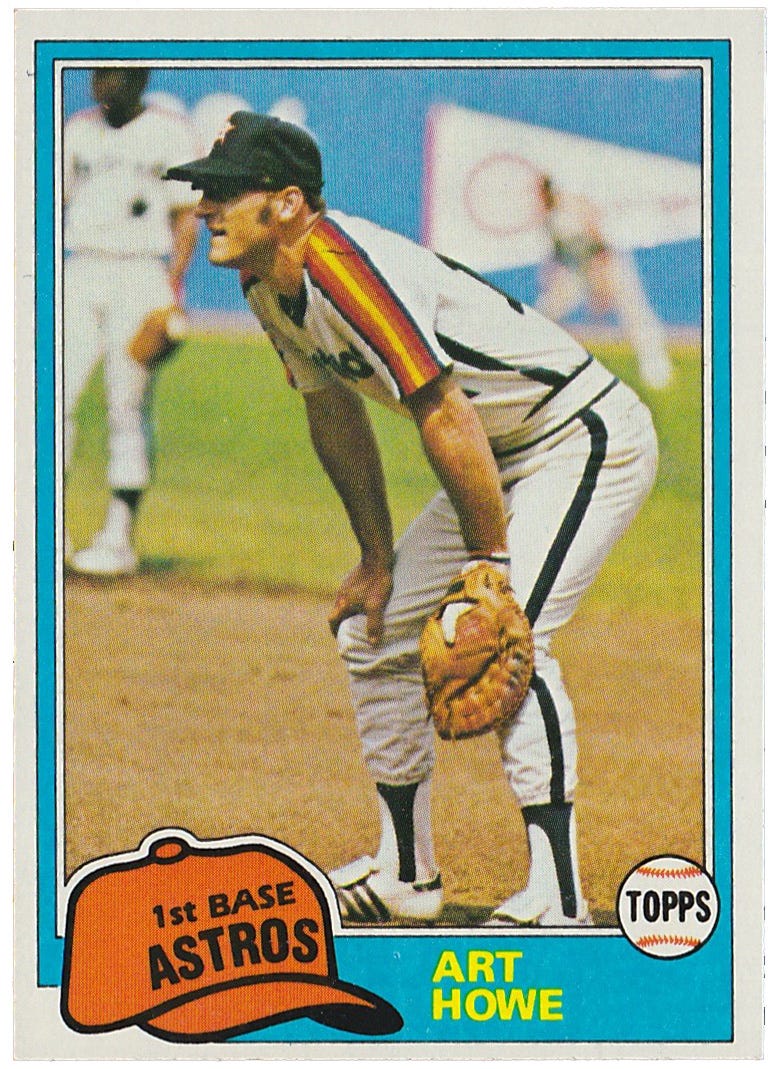

Pop of the Topps: 1981

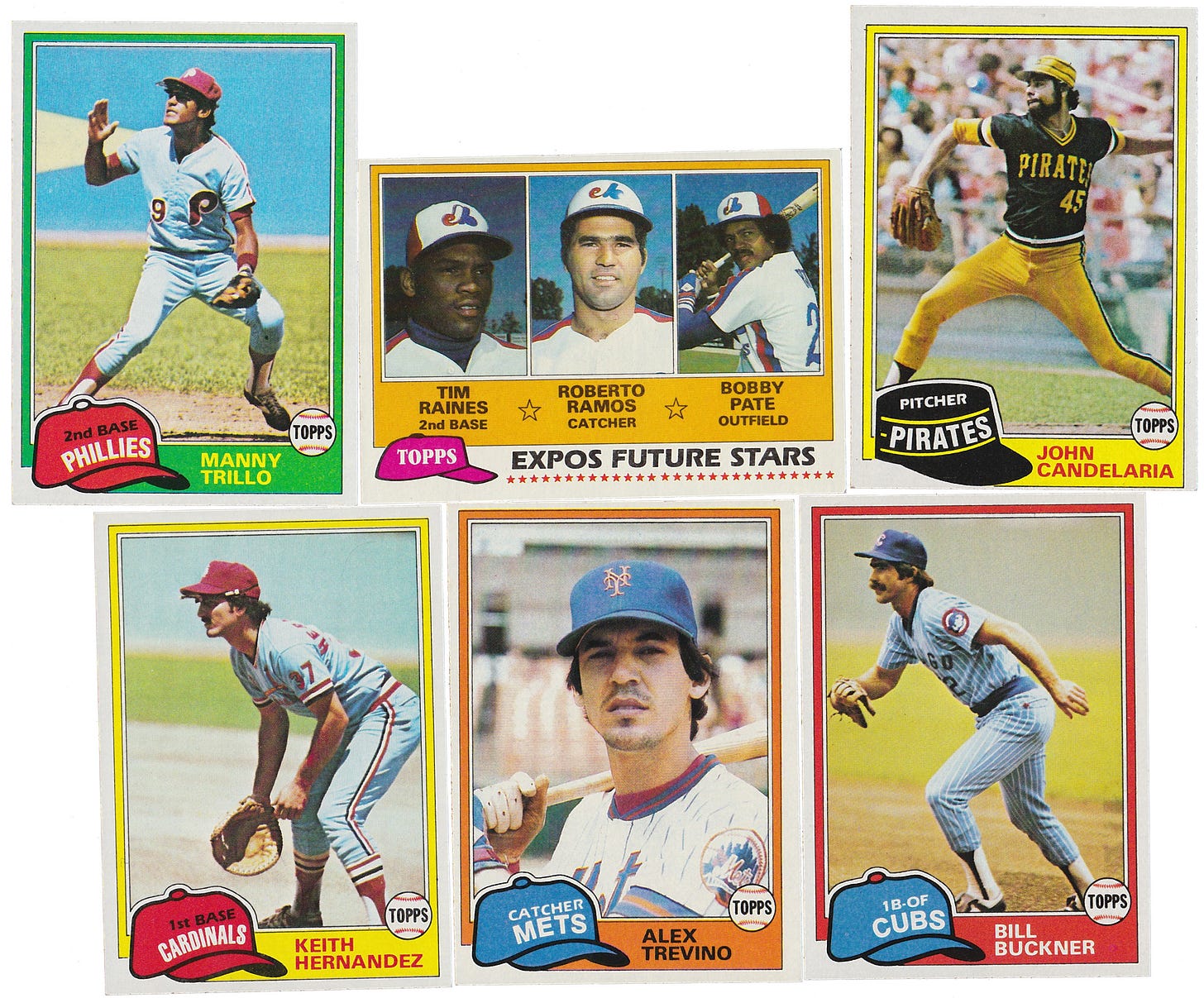

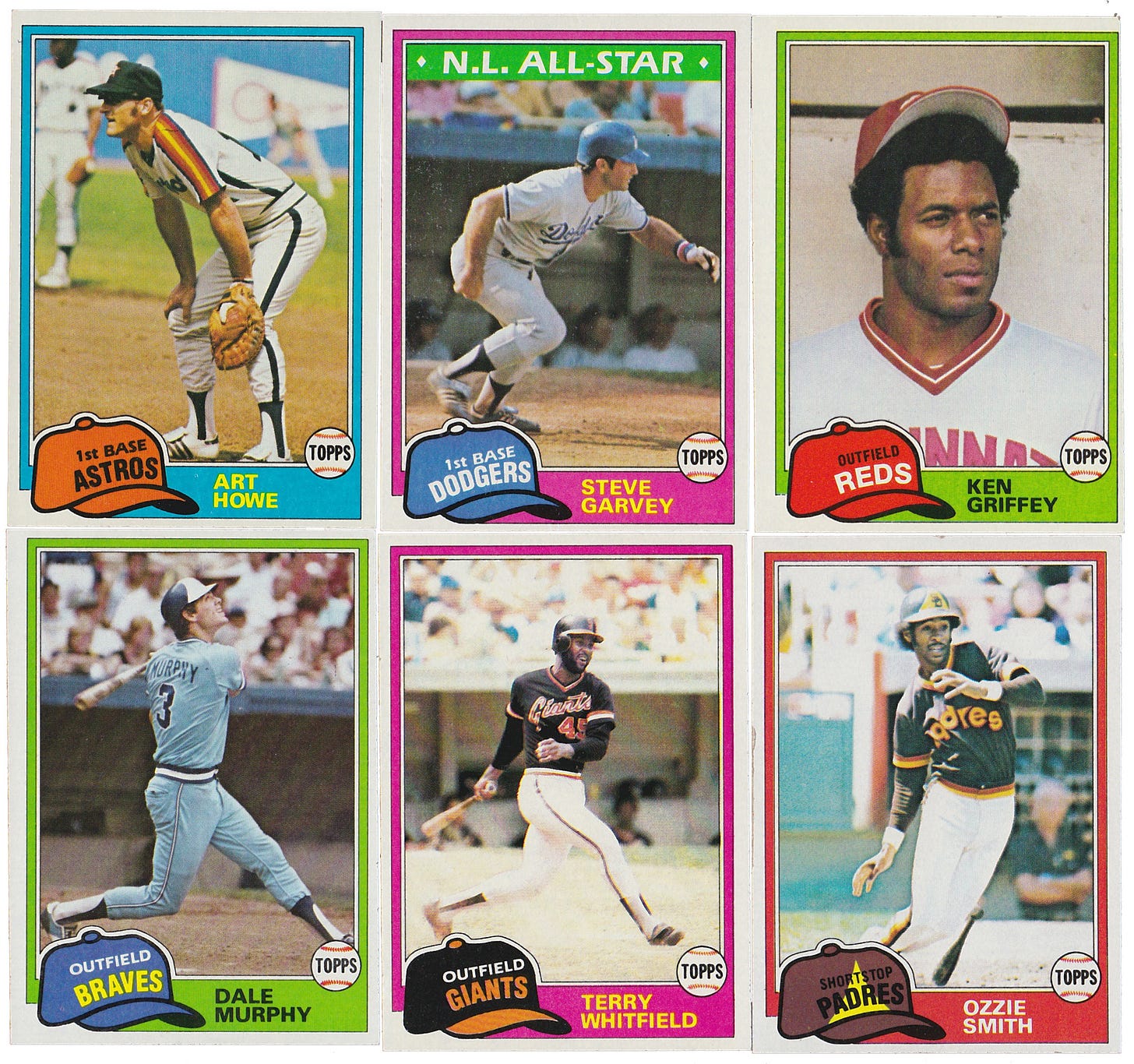

Back in Issue 71 in July, I determined what I believe to be the best card in the 2021 Topps flagship set via a sort of baseball-card-aesthetics virtual season, picking the best card from each team, then the best from each division, then from each league, and finally the best in the set. I was hoping to return to that concept this offseason, and with this being a particularly rough week with regard to baseball news, this seemed like the perfect time.

I’d love to ultimately do this for every Topps set since 1952, but that would take more than a year, so I thought I’d bite off something a bit more feasible, and aimed more directly at The Cycle’s readership by starting with the Topps sets from the 1980s. However, as you can see above, I’m not starting with 1980. Despite Topps’ notorious attempts at airbrushing players into their new uniforms, baseball card sets more often than not depict the previous year’s season, thus I’m starting with 1981, because that’s the set that depicts the 1980 season. It also has a notoriously goofy design, and defining 1980s Topps as 1981 to 1990 bookends the decade with what I believe are two of Topps’ ugliest sets, which, if nothing else gives things some symmetry.

As I wrote in July, my criteria here are purely aesthetic. I’m not ranking these cards by potential value or importance. The player pictured barely matters at all. What matters is that it’s a good photo, well-framed, that fits well within the card’s design. These cards are the ones that come closest to what I think a baseball card should look like. Bright colors, clean, crisp photography with the right amount of light, and some compelling details. Action shots were still in the minority in 1981, so some of these cards did make the cut in part due to the handsomeness of their subjects, though I tried not to base too many decisions on a players’ looks.

Overall, the 1981 set, for all of the nostalgia it may engender, is an ugly set with a terrible base design and some lousy photography. Many cards that might otherwise have made the cut did not because the photo was to dark or out of focus. That the cards below represent the best this set has to offer should give you some idea of what I mean. Also, I did consider the various non-team cards (the record breakers and league leaders, etc.), and while I have always liked the #404, showing Tug McGraw celebrating the Phillies’ first World Series title, and #205, the Pete Rose record breaker (“Most Consecutive Seasons, 600-or-more-At-Bats”) with Mike Schmidt on-deck in the background, neither made the cut.

In the divisions below, the cards are presented in the order of the standings from 1980, from left to right and top to bottom.

American League East

Yankees: Ruppert Jones #225 I’ve always liked the pink borders on the 1981 Yankee cards. Of the four teams to get pink in this set (also the Tigers, Dodgers, and Giants), I think it works best for New York. Graig Nettles #365, Luis Tiant #627, Rich Gossage #460, and Ron Davis #16 all feature action shots of similar quality to this one, but Jones’s is the most dynamic and thus gets the nod here. The image is framed nicely, with Jones’s legs in the lower corners and his bat whipping through the upper right. The catcher’s glove position and Jones’s eyeline suggest he put a charge into the pitch, and though there’s a shadow on his face, you can make it out. The 1980 season was Jones’s only one with the Yankees and the worst of his 12-year career, but he made his mark with this card.

Orioles: Jim Palmer #210 I almost went with the handsome Ken Singleton #570 here, but then I saw Eddie Murray in the corner of Palmer’s card, and the second Hall of Famer put it over the top. This isn’t the only card of a Hall of Famer in this set with another Hall of Famer in the background, but it is the best looking of that tiny subset. This also isn’t the only Topps card to show Palmer’s signature leg kick, but it is the best of those that do. Palmer was 34 and past his prime in 1980, but he still had a second-place Cy Young finish and another championship in his near future. On other notable Orioles cards from this year, catcher Dan Graham looks like a Tim Robinson character with his soft cap on backwards on card #161, and I like the dugout shot on Eddie Murray #490, but it’s a bit cluttered and framed off-center.

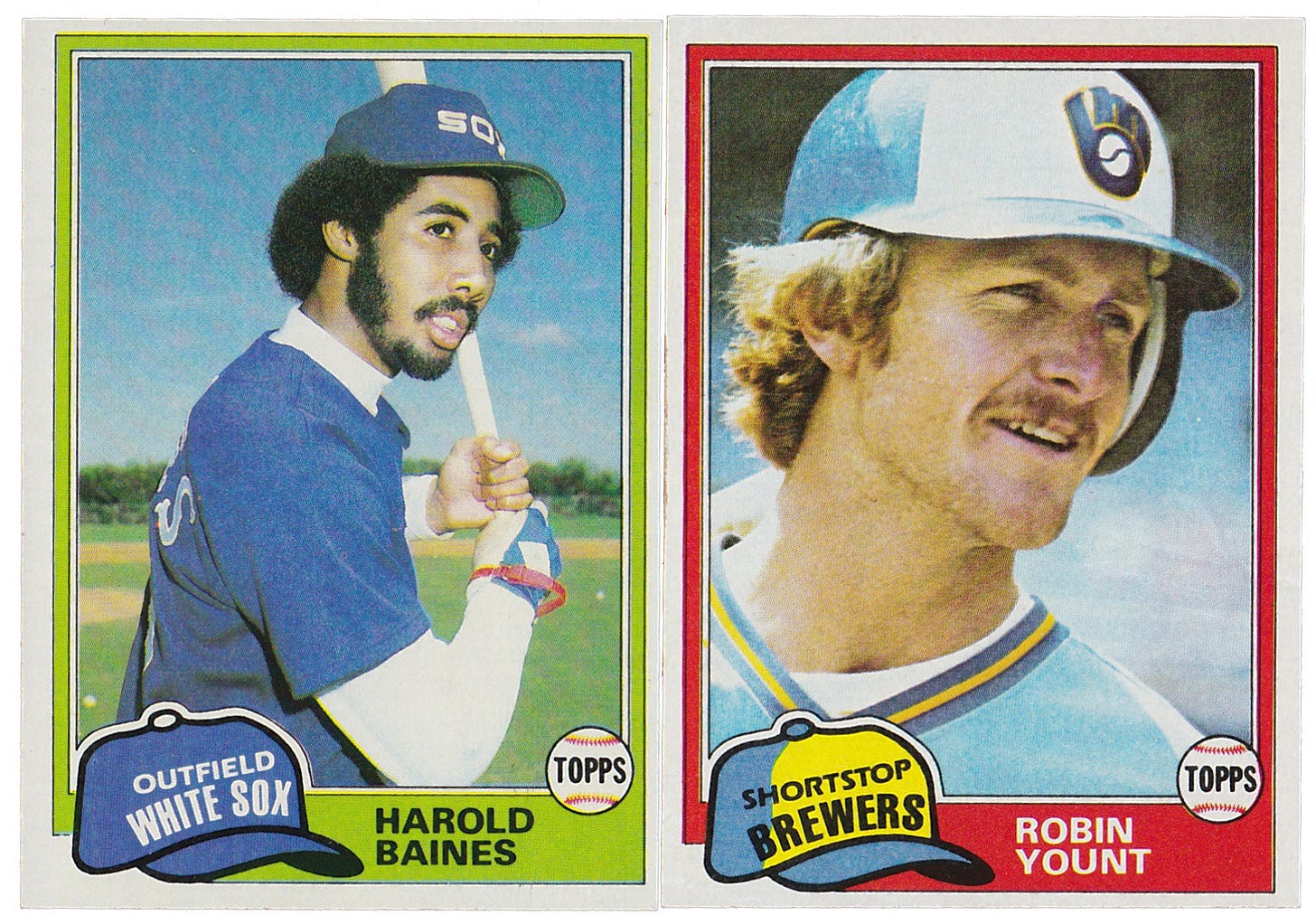

Brewers: Robin Yount #515 This has always been one of my favorites in this set. Yount appears to be leaning over to say something to a teammate during batting practice with his bat slung over his shoulder. It’s framed too tight, but that does add a degree of intimacy, as if Yount is leaning over to say something to you. I also like the uniform detail of the Brewers’ batting helmet. The yellow-front cap depicted on the card design was the Brewers’ road cap at the time. The home caps were solid blue. Yet, for some reason, their batting helmets, both home and road, had a white front. It’s also worth noting that 1980 was Yount’s breakout year. It was his seventh year in the majors, but he was still just 24, and it was the year his power arrived and he became one of the best players in baseball. Runners up are Reggie Cleveland #576 and Paul Molitor’s smirk on card 300.

Tigers: Stan Papi #273 There really isn’t a good Tigers card in this set, and not just because their cap in the design is inexplicably black with yellow type (though that does not help). I chose journeyman utility infielder Stan Papi here because I like the fact that the photographer captured Tiger Stadium’s old-school ribbon scoreboard behind him, but this is a close-up headshot in which you can’t even see the player’s entire face.

Red Sox: Dwight Evans #275 Dewey’s last card before growing his signature mustache. I have a soft spot for cards of players sneering or grimacing (Jeff Reardon’s 1988 Topps is a particular favorite), and I love the way this appears to be a candid head shot. Chosen over Carl Yastrzemski #110 (with Carlton Fisk in the background) and Jim Rice #500, on which the photo is too grainy and dark.

Cleveland: Ross Grimsley #170 I didn’t choose this only because there is no Chief Wahoo imagery on this card, though that doesn’t hurt. Incidentally, the card has it right, these Cleveland caps did not have a contrast-colored button (though it will get that wrong on some others to come). I suppose you could call this a handsome-player card, but Grimsley wasn’t nearly as handsome as he looks on this card. A veteran who debuted with the Reds in 1971, Grimsley began a hair journey when he was traded to the Orioles after the 1973 season. He also tried a variety of mustache shapes, and a full beard in 1979. He finally seems to have gotten everything spectacularly right in 1980, though maybe Topps just caught him on a good hair day. Grimsley went out on top; this was his final Topps card. Chosen over the more collectable Joe Charboneau #13.

Blue Jays: Ernie Whitt #407 An original Blue Jay, catcher Ernie Whitt was a signature player during the Blue Jays’ first decade, and I like the way the Blue dugout frames him here, even if it’s uneven. I also have a soft spot for casual pictures of players with their caps tilted back on their heads. Add the catcher’s glove and associated batting glove, and there are a lot of nice details here. Demerits: that green boarder and the fact that the button on the Blue Jays’ cap should be blue. Not much competition here. Lloyd Moseby #643 and Alfredo Griffin #277 had potential but squandered it.

AL East Champion: Robin Yount #515

American League West

Royals: Willie Wilson #360 Handsome star player with his hat tipped back and a bit of a squint. That’ll work. Over U.L. Washington’s toothpick and Afro on #26 and Darrell Porter’s Coke-bottle specs on #610. The 1980 season was Wilson’s best, worth 8.5 wins above replacement per Baseball-Reference. Too bad Topps hadn’t adopted bold and italic text for league leaders yet, Wilson led the majors in at-bats (705), runs (133), hits (230), and triples (15) that year, all of which appear in plain text on the back of this card.

A's: Jeff Newman #587 Comparable to Tony Armas #629, as both photos were clearly from the same photographer at the same game and very likely the same inning. Just edges Mike Norris #55, which has a more dynamic photo. However, Armas and Norris are both a touch less crisp, and the Norris card has a weird, distracting illusion going on with his right leg. Also, the A’s cap button should be yellow.

Twins: Geoff Zahn #363 I was tempted to go with Rick Sofield #278, a handsome-player card that lists my hometown on the back (it’s where Sofield lived at the time; I later had him as a guest instructor at a local baseball day camp near the end of the decade). I also tempted by Al Williams #569 because of Williams’ kid-on-the-curb pose, with his glove on his knee in front of what looks like the Tiger Stadium dugout (Tiger Stadium, along with the two New York ballparks and Spring Training, was one of the most popular cites of baseball card photos back in the day). Ultimately, I liked how Zahn’s legs outlined the Twins cap (needs a blue button!) and the fact that you can see the “TC” on his stirrup.

Rangers: Pat Putnam #498 Yes, this is really the best Rangers card from this set: various shades of blue accented by red and white and a good look at that sleeve patch, which was introduced for 1976 with the centennial years in the blue section, then retained without the dates through 1982. Runner-up was Jim Kern #197, as Kern appears to be hanging his head after a dramatic comedown from his remarkable 1979 season (he’s probably reading or signing something). That one has an arty feel given the context, but the photograph is not crisp, and is ultimately a side view of a player with his eyes nearly closed with few compelling details.

White Sox: Harold Baines #347 There’s no real competition for the tidy pic on Baines’s rookie card among the White Sox cards in this set. That it is Baines’s rookie was not a factor here. I didn’t even realize that was the case until I started writing this. Steve Trout #552 is a particularly terrible card even among this lot.

Angels: Carney Lansford #639 I love the lighting in this card. It’s that orangey, late afternoon sun setting behind home plate at Yankee Stadium (note the shadow of Lansford’s glove on his jersey). I don’t think there’s another card in this set with that kind of lighting. Honorable mention to Brian Downing #263, which has a shot of Downing in his batting stance from an angle that makes it look like Downing is sticking his butt out at the camera and is cropped such that it appears the catcher is reaching into the frame grab him.

Mariners: Mike Parrott #187 This is not a good baseball card, but the Mariners in this set don’t have many (any) that are clearly better. Maybe Julio Cruz #397, a batting cage shot that catches some Tigers and Mariners fraternizing in the background. This Parrott card is so of its moment, however, with the hair, and the aviators, and that trapped-in-amber Seattle roadie with the sleeve patch adopted when the All-Star Game was held in Seattle in 1979, which would become the Mariners’ primary logo in 1981. And why is he wearing a red shirt under his jersey? Plus, you can see well into the stands at Tiger Stadium, including the sign for section 227. Parrott went 1-16 with a 7.28 ERA in 1980. So, even if you don’t think this is the best Mariners card in this set, it is the most Mariners card in this set.

AL West Champion: Harold Baines #347 (just barely over Carney Lansford)

National League East

Phillies: Manny Trillo #470 The card I have on the spine of my 1981 Topps album is Mike Schmidt #540, because he was the NL MVP from the 1980 World Champs, the best third baseman in major-league history, and the card has a unique photo of Schmidt appearing to shout instructions to his fellow infielders (maybe he’s helping Trillo find that flair that seems to have sailed right into the sun). However the photo on the Schmidt card is washed out, the colors faded. This Trillo card pops in a way the Schmidt doesn’t, and I like the dynamism of the image. You can just see the ball on its way to Trillo as he fights the sun.

Expos: Future Stars #479 It’s not just that this is Tim Raines’s rookie card, which makes it, for my money, the top prize in the set (though I have no idea if it’s actually the most valuable, I suspect it is not). It’s that all three players are wearing crisp white home uniforms, none of the three is photoshopped (or in black and white, which Topps would sometimes do out of desperation on these multi-rookie cards), you can see the name and number on the back of Bobby Pate’s jersey. The Raines photo is a little dark, but I just love this card. Incidentally, Topps did get the Expos’ cap colors right on the rest of the team cards.

Pirates: John Candelaria #265 I like that Topps made a unique pillbox shape for the Pirates caps in this set, and included some of the piping, as well. They left out the yellow button, but there are obviously space issues there with the position listing. Still, that pillbox-shaped cap design is even uglier than the regular one on the cards of the other 25 teams. There are other Pirates cards that arguably surpass Candelaria’s—Phil Garner #573, Mike Easler #92, Willie Stargell #380, Bert Blyleven #554—but those players (save Blyleven, who is in closeup) all have matching jerseys and pants (Garner in all white!), and that just doesn’t feel appropriate for the Pirates of this era.

Cardinals: Keith Hernandez #420 The Cardinals wore their uniform numbers on both sleeves in 1979 and 1980, and it was tempting to go with Silvio Martinez #586, which shows that, but it’s not a good picture beyond Martinez’s duel #35s. There really wasn’t much competition for Keith here, and I’m fine with a card of arguably the greatest-fielding first baseman off all time in a ready position in the field, with his stripped stirrups and sleeve number. I just wish we could see his face better.

Mets: Alex Trevino #23 One of my favorite cards in this set is John Pacella #414, which shows the righty swingman in his follow through, with his cap, having fallen off his typically bushy head, just an inch or two from hitting the dirt. It’s a perfectly timed photo, with the cap hovering just above it’s own shadow, but the rest of the photo isn’t great. The Trevino card, by comparison, is one of the most handsome in the set. The Mets get the benefit of having their team colors in the border, and even though the Trevino photo is a closeup, it’s filled with details, from the stripes on his uniform, to that classic Mets patch, to his batting gloves and bat. It’s just a good, sharp photo. I just want to drag it up ever so slightly in the frame.

Cubs: Bill Buckner #625 The 1981 set is filled with photos of first basemen in the field taken from the first-base photographer’s box: Hernandez, Buckner, Willie Aikens, Art Howe, Bob Watson, Dan Driessen, John Milner, Chris Chambliss, Mike Jorgensen. It’s like its own little subset. This Buckner card is far from the best of those, but there aren’t any real standout Cubs cards, and I wanted one with a good look at that reverse-pinstriped roadie the Cubs wore from 1978 to 1981. Bruce Sutter #590 has a good photo in the abstract, as it has both Sutter and the ball, mid-flight on the way to home plate, in the frame, but Sutter’s face is in dark shadow, his follow-through obscures the uniform, and the green “N.L. All-Star” banner messes up the color scheme. So, Buckner. Spoiler: he won’t win the division.

NL East Champion: Alex Trevino #23

National League West

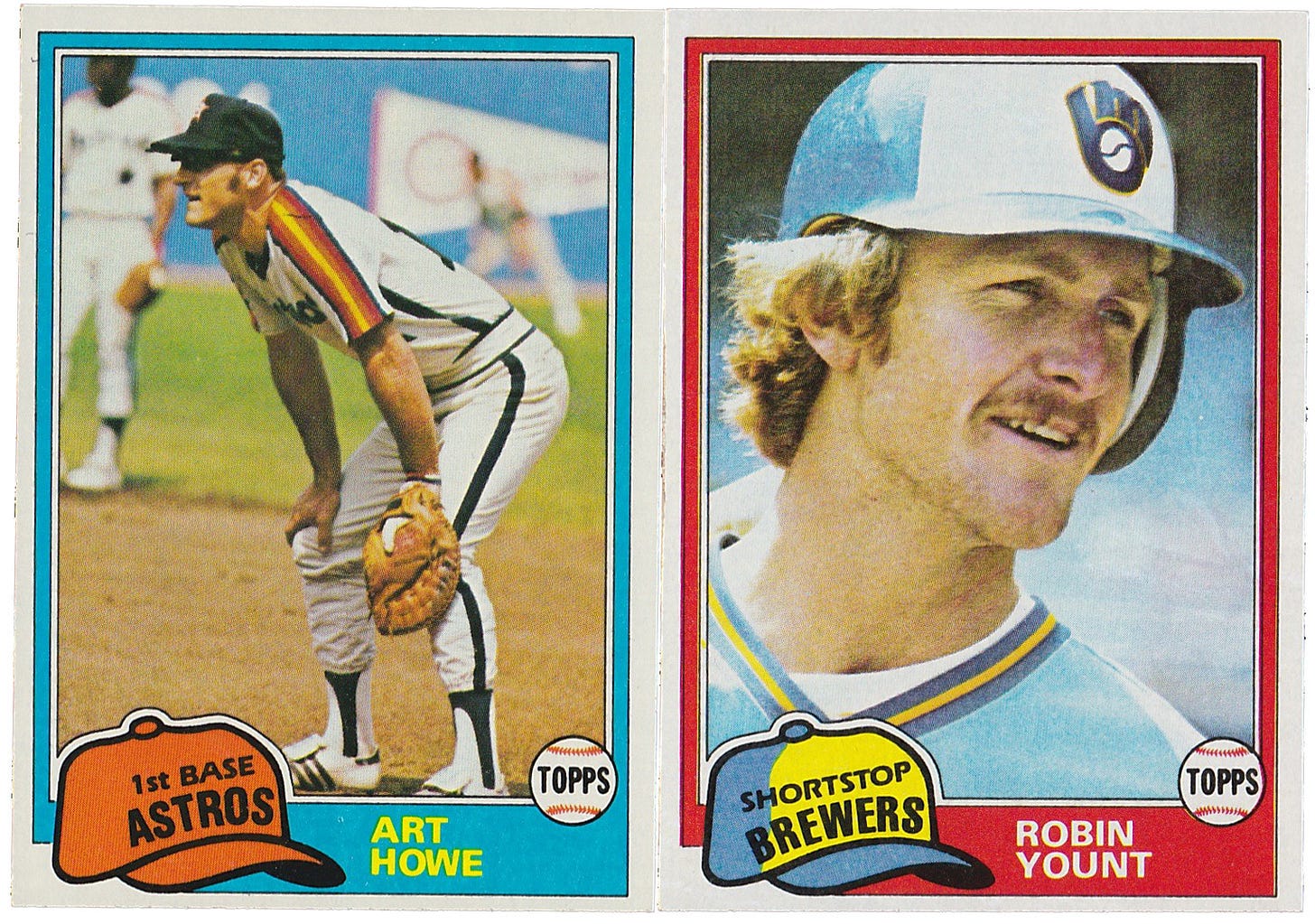

Astros: Art Howe #129 This is the best of those first-basemen-in-the-field cards. The colors just pop, with those tequila-sunrise shoulder stripes (this was Houston’s road uni at the time, they still wore the full-blown tequila sunrise jerseys and orange caps at home), the orange cap and blue border picking up those colors from the photo, the brown dirt, green grass, and Shea Stadium’s blue outfield wall. Then there’s the tremendous depth of field, which captures the second baseman (Hall of Famer Joe Morgan, though you can’t really tell it’s him), center fielder, and the pennants on the wall. The color scheme makes the Astros one of the best-looking teams in the set, but this Howe card is plainly the best of Astros card in the set. Honorable mention to Nolan Ryan #240, Ryan’s first Astros card.

Dodgers: Steve Garvey #530 If the photo wasn’t so dark and grainy, I might have gone with Rookie of the Year Steve Howe #693, and I was tempted by Pedro Guerrero #651 and Bob Welch #624, which find those two in similar reclined poses in the dugout. Dodgers Rookie Stars #302, with Fernando Valenzuela and Mike Scioscia, is one of the most collectible in the set, but not much to look at. So, Garvey, because I like the action, though I hate the green “All-Star” banner against the pink border.

Reds: Ken Griffey #280 Handsome player with a bit of a squint and his cap set back. Bad background, but the Reds cards in this set do not look good. The green border was a bad choice, and Tom Seaver #220 is too dark. Griffey reminds me of a bit of Marlon Wayans in this photo, though he’s more of the Keenan Ivory to Junior’s Marlon, if we’re grafting the Griffeys on the Wayanses.

Braves: Dale Murphy #504 Not much to chose from on the Braves, either. Here we have a nice action photo of the team’s best player, showing his name and number and another unique batting helmet (the Braves never had a white bill on their caps). Though they stopped wearing the Hank Aaron-era feather-sleeved uniforms in 1980, the Braves kept the corresponding white-front caps (and white-billed helmets) around for one more season. As with Yount, 1980 was Murphy’s age-24 and breakout season. It was his first in center field, and his first resulting in an All-Star appearance.

Giants: Terry Whitfield #167 Jack Clark’s unibrow on #30 is glorious, and Joe Pettini does a good Father Guido Sarducci impression under the airbrushing on #62, but neither is a terribly attractive card. There are other Giants action shots comparable to Whitfield’s, but his is the most dynamic and gets the nod. After the 1980 season, Whitfield would spend three years in Japan with the Seibu Lions, for whom he hit .289/.333/.527 over his age-28 to -30 seasons, making him the rare established American major-leaguer to spend his prime overseas.

Padres: Ozzie Smith #254 Yes, the fact that this is Ozzie on the Padres gave it a little extra juice. Bob Shirley #49 might be better looking, overall, but this is a very dynamic photograph of Smith, with his bat falling to the ground after contact. I just love the way he seems to be sliding across the frame, it’s almost like he’s dancing.

American League Championship

That Baines rookie is just so clean and crisp, but there’s something more dynamic about the Yount card. It has a personality the Baines card doesn’t.

AL Champion: Robin Yount #515

National League Championship

Blue and orange are opposite colors on the color wheel, and their high contrast makes them an appealing and popular color combination, one that has become extremely common, even in subtle ways, in set design for television talk and news programs and in the tinting of films. Here, we have two examples. The orange and blue, used in opposite ways on these two cards, just looks sharp, and the crisp photography and corresponding uniform colors (or outfield-wall colors in the case of the Howe card) add to the strong impression. These might be the two best looking cards in the set, period, but I have to take Howe over Trevino because there’s actual baseball action and so much more happening in the background (in a good, aesthetically pleasing way, with great depth and a bonus Hall of Famer) in addition to the nice details on the primary subject

NL Champion: Art Howe #129

World Series

Do you prefer clean, simple, and an unobstructed view of the player’s face, or do you prefer game action full of compelling details? Do you want a card that makes you feel like you’re sharing a private conversation with a player, or one that makes you feel like you have front-row seats on the first-base line? I don’t think there’s a wrong answer here. As ugly as the 1981 set may be, and as unlikely as these two cards may be to become part of a conversation about the best Topps cards of all time, these are two great-looking cards. Do you give the Yount extra credit for being a key card in the career of a Hall of Fame player? Or is it more fun to have a future manager during his playing days with a Hall of Famer out of focus in the background?

For what it’s worth, Howe had a career-high 129 OPS+ in 1980 and would pick up some MVP votes in 1981, but he did the former in just 364 plate appearances, and he spent more time at third and second base in his career than first, 1980 being the lone exception. I love that Yount card, but I can’t resist the feeling of being at a game at Shea Stadium in 1980 that the Howe card gives me.

Champion

#129 Art Howe

By the way, the printing flaws on Howe’s shoulder and in the upper left are not unique to my card.

Shameless Self-Promotion

I made my latest appearance on Steven Goldman’s The Infinite Inning this week. We recorded the interview on Monday and Steve released it on Wednesday, so it’s more up-to-the-minute than a lot of my appearances on the show. With the news as slow as it had been prior to mid-week, we started off with a good bit of nerd-culture conversation about special effects, superhero movies, and Star Wars before getting into a baseball conversation that was almost entirely about the labor dispute. I felt a bit off on Monday, so I was pleasantly surprised to hear that you can’t really tell from listening to the show (thanks to Jeffrey Paternostro for editing help there, I’m sure, but also to Steve for always improving my mood and generating engaging conversation). I do think my tone is a bit sharper at the end, though I may be projecting (if it’s even possible to project onto yourself). At any rate, please enjoy:

(Because everything is poison these days, I feel the need to address the fact that the above is a Spotify embed. The Infinite Inning is hosted by Baseball Prospectus, not Spotify. You can listen to it there, or via any other “podcatcher,” to use Steve’s term, of your choice. However, Substack allows me to embed Spotify tracks and podcasts, and, given the opportunity, I prefer to make the show available to the readers who are more likely to click and listen here than chase it down via additional steps. You can decide for yourself if it’s worth boycotting Spotify, which does not require a subscription to listen podcasts like this one.)

Feedback

I want to hear from you. Got a question, a comment, a request? What would you like to read about in lieu of actual baseball news? Reply to this issue. Want to interview me on your podcast, send me your book, bake me some cookies? Reply to this issue. I will respond, and if I find your question particularly interesting, I’ll feature it in a future issue.

You can also write me at cyclenewsletter[at]substack[dot]com, or @ me on twitter @CliffCorcoran.

Closing Credits

Depending on your source, the biggest hit of 1980, according to Billboard was either Blondie’s Giorgio Moroder collaboration “Call Me,” from the American Gigolo soundtrack, or Kenny Rogers’ Lionel Richie collaboration “Lady.” I have thoughts and feelings about both (almost entirely positive in both cases), but I wanted to dig beneath the pop charts for a 1980 song that meets our current moment, “Start!” by the English mod-punk trio the Jam.

Penned by the Jam’s singer, guitarist, and primary songwriter, “Start!” was the lead single from the band’s penultimate album, 1980’s Sound Affects. Released ahead of the album in August, “Start!” became the Jam’s second UK number one, though it only scraped the Dance charts in the U.S. Effectively a rewrite of the Beatles’ “Taxman,” which Weller used in more than one song from around this time without giving George Harrison a song credit, though Harrison may have understood given the fallout from “My Sweet Lord,” “Start!” expresses a typical punk-era disaffection that can be read as both romantic and political. I’m choosing the latter interpretation here, as the key line, “what you give is what you get,” seems perfectly suited to baseball’s ongoing labor negotiations.

The title comes from the line in the second verse, “if we get through for two minutes only it will be a . . . start!” Again, you can take that multiple ways, but the interpretation that works best, in my opinion, is that it’s a plea for communication (in the first verse, that is made explicit, but one could still interpret the word “communicate” a few different ways). The “two minutes only” is the length of the song you are listening to (2:20, officially).

Here’s hoping MLB’s owners are willing to start (start!) really communicating with the union, and understand that, in any negotiation, what you give is what you get. That has certainly been the case thus far.

The Cycle will return next week to pore over how things have developed on the labor front and, barring bigger news, find the best card from the 1982 Topps set.

I'm glad to see an American appreciating The Jam. 👍

Well, now I’m gonna have to pull out my 1981 binder and check it out! (It’s been quite a while since I thumbed through that set.)